Why the United States must bridge the Iraq-Syria divide

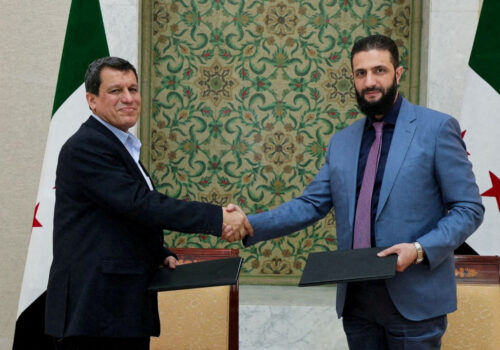

On March 10, 2025, the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)-led government in Damascus and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) signed a landmark peace deal marking the first formal recognition of Kurdish rights in modern Syrian history. The deal, empowered by US and French diplomats, not only promises constitutional recognition for the Kurds but also tempers Turkish threats against the SDF, a key US ally in the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS).

While this accord sets Syria on a tentative path toward stability and minimizes the chance of another civil war, its implications reverberate across the region—most critically for Iraq, Syria’s neighbor sharing its second-longest border. Yet, Baghdad’s hesitation to engage with the new Syrian government threatens to undermine potential security cooperation at a time when the ISIS threat persists, placing the United States in a pivotal position to mediate.

Iraq’s reluctance: Historical baggage and regional politics

Iraq’s reluctance to engage with Damascus in the aftermath of the HTS-led overthrow of Assad in December is complicated by Baghdad’s past alliance with the ousted regime, bolstered by mutual interests in countering mostly Sunni radical opposition forces.

For decades, Syria-Iraq relations have been marked by diplomatic cuts and tensions, despite both nations adopting Baathist ideology under Hafez al-Assad and Saddam Hussein. After 2003, the Assad regime refused to recognize Iraq’s new government and was accused of facilitating jihadists crossing into Iraq to join al-Qaeda. However, in 2011, things changed when then-president Bashar al-Assad lost control over large swaths of Syrian territory to opposition groups. The resulting vacuum was exploited by ISIS, which seized a third of Iraq in 2014. This triggered a costly three-year war for Iraq, supported by billions in US aid, to reclaim its land.

A significant number of Iraqi Shia militia units, often operating under Iranian command, fought alongside Assad’s forces against groups like HTS and ISIS, forging deep operational ties. Assad’s fall, widely perceived as a setback for Iran and its “Axis of Resistance,” has left Iraq’s policy toward Syria in disarray. Iran’s influence in Baghdad, coupled with the presence of Iraqi militias once active in Syria, complicates any swift pivot to recognizing interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa’s government.

Adding to this reluctance is a lingering legal and moral quandary: Iraq still holds an arrest warrant against al-Sharaa, formerly known as Abu Muhammed al-Joulani, for his past affiliations with al-Qaeda and alleged involvement in attacks that killed Iraqis. Iraqi policymakers are, therefore, skeptical of al-Sharaa’s transformation on the world stage into a pragmatic statesman. Since Assad’s ousting, Baghdad has cut oil supplies to Syria, postponed a proposed visit by Syria’s foreign minister over objections from Shia politicians, and kept its two major border crossings with Syria—vital for trade and security—nonfunctional. The deployment of Iraq’s largest border patrol since the 2017 liberation of Mosul signals heightened caution rather than cooperation.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

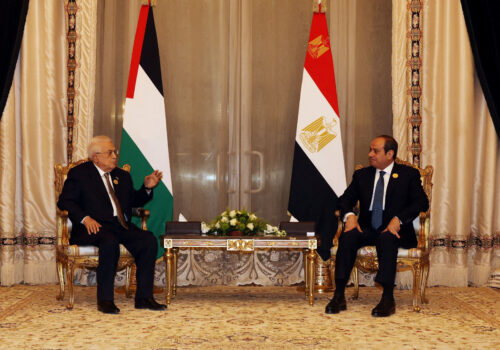

Baghdad discreetly hosted Syria’s foreign minister last week, in an unannounced and unprecedented visit for a foreign minister of a neighboring country that caused significant backlash Shia figures disapproval. While discussions included Baghdad’s concerns over Shia shrines and the protection of Alawite communities, the primary focus was establishing border security cooperation. However, achieving meaningful progress in this area requires intensive diplomatic engagement that neither side appears capable of sustaining independently at present.

In recent days, unknown armed groups have targeted Syrian workers in Iraq who shared or showed support for Syria’s new ruler, al-Sharaa, on their social media profiles. Iraqi security forces arrested some others for posting content that endorsed Damascus’ security forces actions in Syria’s coastal cities, which reportedly led to the killing of hundreds of Alawite civilians. Iraqi law charges any affiliation with al-Sharaa under Article 4 of its anti-terrorism law.

Yet, this stance is not uniform across Iraq. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) has taken a pragmatic approach, endorsing the new Syrian leadership and playing a key role in bridging gaps between al-Sharaa and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) leader Mazloum Abdi. Kurdish leaders, including the KRG president and prime minister, have met Syria’s foreign minister in Europe, signaling support for the peace deal. Iraq has been represented primarily through its Kurdish-led foreign ministry at regional meetings on Syria, and Iraqi Sunnis, too, have expressed sympathy for Damascus’s new rulers.

But Baghdad’s federal government has maintained a distance, showing little inclination to normalize relations. Only a brief visit by the intelligence chief to Damascus yielded no tangible progress.

Regional endorsements and divisions

The new Syrian government has garnered broad regional support, with endorsements from the Gulf states, Lebanon, Egypt, Jordan, and Turkey. These nations, seeking stability in Syria, have welcomed the HTS-led administration as a potential partner in rebuilding and securing the region. Europe took the lead in normalizing relations with Damascus’s new government.

However, the United States has yet to formulate its official diplomatic position, although its military has coordinated with new Syrian security forces to counter ISIS. Following the deal with SDF, Washington now possesses a reliable and strong partner within the new Syrian government, at least for security and counterterrorism operations. However, Israel and Iraq stand apart, refusing to accept the leadership change in Damascus. Israel’s concerns likely stem from HTS’s Islamist roots and its potential ties to groups hostile to Israeli interests, while Iraq’s reluctance is driven by the aforementioned historical and political factors. Israel launched military operations into southern Syria in a bid to demilitarize Damascus’ defense capabilities along its border. Iraq, on the other hand, refuses to reopen its border crossing, and flights between Baghdad and Damascus have stopped.

Security cooperation at risk: the ISIS factor

The stakes of Iraq’s hesitation are high, particularly regarding security cooperation against ISIS, which remains a potent threat along the Iraq-Syria border—a fragile region ripe for exploitation. Normalizing relations with Damascus, starting with joint military cooperation at the border could bolster joint efforts to secure this porous frontier, where thousands of Iraqi ISIS affiliates languish in SDF-controlled prisons and camps like Al-Hol in Syria’s northeast. A coordinated approach could prevent the group from capitalizing on any power vacuum in a divided Syria, a scenario that previously saw ISIS seize a third of Iraq in 2014, triggering a costly three-year war and billions in US aid to reclaim lost territory.

Baghdad’s current standoffishness, however, risks the opposite. Without formal engagement, intelligence sharing and border coordination remain stymied, potentially allowing ISIS to regroup. The United States stands to lose ground in its long-standing campaign against the group if tensions between Baghdad and Damascus persist, especially considering Washington’s significant military partnerships with both the Iraqi army and SDF. The peace deal’s promise of extending US influence on the HTS-led government via the SDF strengthens internal security, but to achieve long-term cross-border security, Syria needs Iraq as a reliable partner.

Mediating a Fragile Triangle

The United States emerges as the linchpin in this delicate equation. Having quietly engineered the HTS-SDF accord—evidenced by the American Chinooks ferrying Abdi to Damascus—the United States now has a reliable partner in Syria’s new military, thanks to the deal’s integration of the SDF into Syria’s defense framework. Coupled with its formal alliance with Baghdad, this positions the United States to bridge the gap between the two nations. Washington holds leverage over both capitals: Iraq relies on US military support and seeks to avoid sanctions, while Syria’s new government needs international legitimacy and reconstruction aid, both contingent on US goodwill.

Washington could press Baghdad to move beyond historical grievances and engage Damascus, emphasizing the shared threat of ISIS. Facilitating dialogue—perhaps through joint military coordination at border crossings—would align with US strategic interests in stabilizing the region and safeguarding its investment in the anti-ISIS coalition. Simultaneously, the United States could encourage Damascus to address Iraq’s concerns, such as resolving the status of Iraqi detainees and preventing anti-Alawite sentiment, to build trust.

A Path Forward

The HTS-SDF peace deal offers a rare opportunity for regional stability, but Iraq’s refusal to engage Damascus risks squandering its potential. Caught between historical loyalties and contemporary realities, Baghdad’s indecision threatens security cooperation at a critical juncture. The United States, with its military footprint and diplomatic clout, must step in to bridge this divide, leveraging its partnerships with both Syria’s new military and Baghdad to align the two nations against ISIS. Failure to act could see the region slide back into the chaos that once empowered extremists—a cost neither Iraq, Syria, nor the United States can afford.

Sarkawt Shamsulddin is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs and was a member of the Iraqi Parliament from 2018 to 2021. When he was elected in 2018, he became the youngest Iraqi member of parliament at the age of thirty-four.

Further reading

Wed, Mar 19, 2025

Trump’s military cudgel in Yemen will not achieve US regional objectives

MENASource By

Donald Trump risks falling into US pattern of short-sighted military action at the expense of constructing a sustainable plan for Yemen.

Tue, Mar 18, 2025

Landmark SDF-Damascus deal presents opportunity, and uncertainty, for Turkey

MENASource By Ömer Özkizilcik

Despite positive signals, critical ambiguities remain in agreement between Syrian President Ahmed Shara and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi.

Mon, Mar 10, 2025

Trump should embrace the Egyptian Gaza plan. It’s his best chance to secure peace.

MENASource By

The Egyptian plan offers a base to secure many parties' interests and create the required regional stability to buy time for diplomacy.

Image: Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani meets with Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad Hassan al-Shibani, in Baghdad, Iraq, March 14, 2025. Iraqi Prime Minister Media Office/Handout via REUTERS ATTENTION EDITORS - THIS IMAGE WAS PROVIDED BY A THIRD PARTY.