With the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) in Yemen concluded on 25 January 2014, the constitution-drafting period will focus on incorporating the outcomes of the NDC discussions into the new national charter. A close examination of the outcomes of the NDC may help address any shortcomings in the NDC agreements during the constitution-drafting process.

With the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) in Yemen concluded on 25 January 2014, the constitution-drafting period will focus on incorporating the outcomes of the NDC discussions into the new national charter. A close examination of the outcomes of the NDC may help address any shortcomings in the NDC agreements during the constitution-drafting process.

One of the key, attention-grabbing outcomes of the NDC is the transformation of Yemen into a federal state. Addressing the extreme centralization of power was one of the main demands of the protestors in 2011. In addition, the secessionist demands of the Southern movement (known as Southern Herak) that gained momentum since 2007 meant that a radical solution to the centralization of power in Yemen had to be reached. The ex-regime in Yemen gutted the Local Authority Law (intended to decentralize authority by establishing locally elected district and governorate councils) and its application from any real meaning, so promises of improving the current system of local authority were no longer accepted, especially by the Southern Herak. A federal system was seen as the only politically-acceptable solution that would address the issue of centralization and transfer power and authority to be closer to the citizens in the different areas of Yemen.

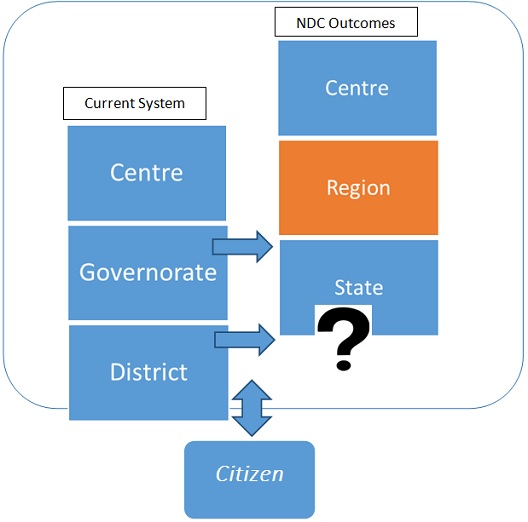

The current administrative system in Yemen consists of three levels of government: Central government in Sana’a, Governorate-level councils, and District-level local councils. Since the beginning of the NDC, many delegates, activists, and experts emphasized the importance of distributing power to the “third level of government” (district-level local councils) and protecting the powers of local authorities by including them in the constitution. This proposal was generally viewed as necessary, irrespective of any NDC steps towards decentralization.

As heated negotiations on the Southern Issue and the form of state progressed, however, a new administrative layer began to shape the discussions on federalism: namely, the “regions.” The Southern movement pushed for a two-region federal system as an alternative to their demands for secession. Gradually, over the weeks and months of the negotiations, a new administrative structure for the new Federal Yemen emerged. The final document ratified by the NDC delegates adopted a federal system with a three-tiered system of government: central, regional, and state governments.

States are understood to be the current governorates, while the new regions and their exact number have yet to be decided (anywhere between 2 to 6 regions, with every region containing a number of states).

Under the structure proposed by the NDC outcomes, and specifically by the Southern Issue Solutions Agreement, the “third level of government” effectively became the state level (previously known as governorate level) due to the addition of the regions layer as shown in the figure. Statements from the NDC delegates and supporting international actors gradually became focused on devolving power and authority to the regions and states, displacing the focus on local councils. In reviewing the State Building Working Group final report, the delegates deferred the section on state structure to the outcomes of the Southern Issue Working Group, which adopted the three-tiered system of central, regional, and state governments. However, another section of the State Building Working Group Report stated, “the division of each region into local administrative units (to be called governorates or municipalities or cities), and into districts.” The group also adopted that each administrative unit should have elected councils, and that Regional Law shall specify the purview of these administrative units. In comparison, the Southern Issue final report clearly states that “the three levels of government (central, regional, and state-level) shall have independent executive, legislative, administrative, and financial authorities as stated in the constitution.”

The NDC succeeded in creating the basis for a decentralized state in Yemen and redistributing powers away from the center. Yet, the closest administrative units to the citizen with any constitutional authority now lies with the states, creating a fourth level of government (the district-level) whose authorities and responsibilities will be determined by regional laws.

A four-level system is more complex and costly than a three-level system. Nonetheless, due to the political realities on the ground, Yemen will now have to adapt to a four-level system. The question that the constitution-drafting committee will have to address is whether to include a fourth-level of government in the constitution and grant this fourth-level constitutional authority and power, or whether to leave it up to each region to decide on the structure, authorities, and responsibilities of its fourth-level of government. The end result will have significant impact on defining the relationship between the new federal Yemen and its citizens.

Rafat Al-Akhali is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. He is also the cofounder and chairman of Resonate!Yemen, a youth-oriented NGO working to bring the voices and ideas of young Yemenis to the public policy discourse.

Image: Agricultural terraces near At Tawilah, Yemen. (Photo: Wikimedia)