From Adam Piore, Popular Mechanics: The first warning that hackers had penetrated the American oil company came soon after the initial breach, in the summer of 2009. The computer help desk received complaints from employees who were locked out of their accounts or whose computers had already been logged onto.

Then the complaints abruptly ceased: The digital spies had obtained an administrator password and were intercepting help-desk tickets, unlocking accounts, and notifying users that their problems had been fixed. With that access, the hackers copied thousands of confidential emails—including those of top executives—and transmitted them to China in massive files late at night, after the oil company’s employees had left for the day.

By the time the FBI informed the company of suspicious network traffic in the summer of 2010, Chinese firms had outbid the oil company on several high-stakes acquisitions by just a few thousand dollars. But it could have been far worse: For months, malware that allowed the hackers to take over terminals had been burrowing deeper into the company’s systems and had wormed its way into computers that controlled oil-drilling and pipeline operations.

"People were alarmed that their email was compromised, but the hackers could have crippled the business," says Jonathan Pollet, the founder of Red Tiger Security in Houston. In early 2011, Pollet helped the oil company identify some of the hackers’ breaches; he refused to name the company, citing a confidentiality agreement.

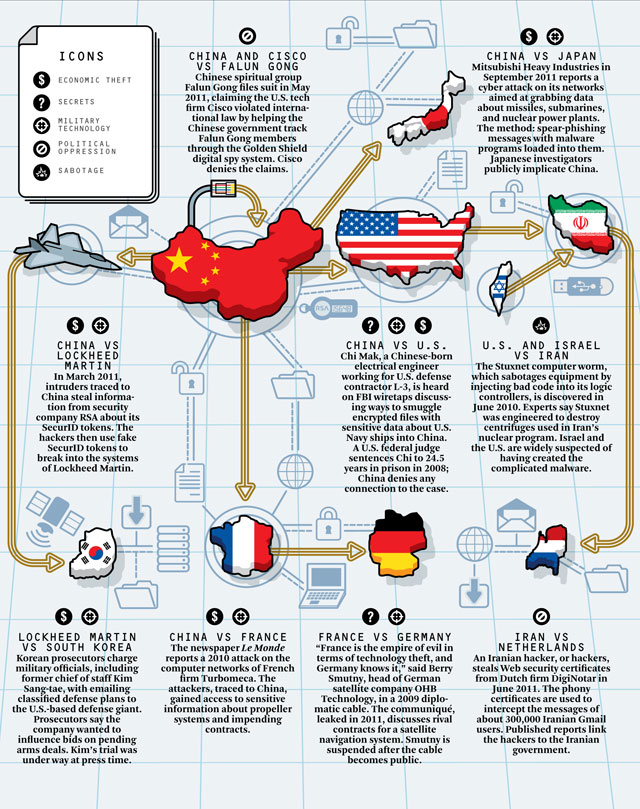

The example Pollet cites is just one incident in an ongoing, aggressive campaign of electronic espionage that costs U.S. firms billions of dollars, endangers our military secrets, and threatens to erode our technological edge, as computer hackers—often but not exclusively traced to China—help their clients, and their countries, gain the upper hand in business deals and steal intellectual property. (An October 2011 report prepared for the Director of National Intelligence titled "Foreign Spies Stealing U.S. Economic Secrets in Cyberspace" explicitly accuses China and Russia of hacking U.S. companies, calling Chinese hackers "the world’s most active and persistent perpetrators of economic espionage.")

The phenomenon blurs the lines between white-collar crime, international spying, and even acts of war, but the attacks are known in the intelligence community as advanced persistent threats, or APTs. Well-financed, patient teams of hackers that U.S. intelligence agencies believe are backed by foreign governments now constitute a major national security risk. The hackers use tactics that are inherently difficult to trace and choose targets that have deep roots within U.S. infrastructure, government, and military. Recent news accounts have identified APT victims that include Google, ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, Morgan Stanley, Dow Chemical, Symantec, Northrop Grumman, and Lockheed Martin, to name just a few.

Private industry is understandably reluctant to reveal such breaches, even to the government: If a digital attack strikes fear in the hearts of a company’s executives, one can only imagine how it would make shareholders feel. But digital spying is like a cockroach infestation—for every one that you see, thousands thrive out of view. "I can’t find an organization, an entity, a business, or a department that hasn’t suffered from cyber intrusions," says Gordon M. Snow, assistant director of the FBI’s Cyber Division. "If they really believe they haven’t, they’re just not aware of it yet."

In August 2011, a report by the security firm McAfee detailed hacks into some 72 public and private computer networks in 14 countries and warned of "the biggest transfer of wealth in terms of intellectual property in history."

Technology theft is the most common motive for digital espionage, but China and other nations have used it to squelch internal political dissent as well. Stolen source code from Google was used to hack into the accounts of Chinese dissidents, and after an Iranian hacker broke into Dutch security firm DigiNotar, the stolen technology was used to help his government spy on troublemakers in Iran. These attacks can cause collateral damage that compromises the security of everyone online. Digital security certificates from DigiNotar were part of the basic verification system of the Internet. If you can fake one of those, you can fool a browser into thinking any site is safe. . . .

Computer espionage has a history almost as long as that of the modern Internet. In the late 1980s, the German hacker Markus Hess and several associates were recruited by the KGB to penetrate computers at American universities and military labs. They made off with sensitive semiconductor, satellite, space, and aircraft technologies. Today, China, Israel, and Russia are reportedly the most aggressive about stealing secrets. But China is playing a game of a different magnitude. "The Chinese didn’t create this problem," [former head of U.S. counterintelligence during the Bush and Obama administrations Joel] Brenner says. "But there’s no question China is the worst offender now. They are all over us. It’s just relentless. . . ."

Byzantine Hades, linked to the People’s Liberation Army Chengdu Military Region First Technical Reconnaissance Bureau, an electronic espionage unit of the Chinese military. According to the cables, Byzantine Hades targeted not only the U.S. government and industry, but also high-level European officials. The Chinese hackers even managed to remotely activate the computer microphones and Web cameras of French officials so they could peek in on everything from office gossip to high-level diplomatic planning sessions. In the past, surveillance like that would have required spies to know where their targets were staying and mic the room—but in the age of cellphones and laptops, spies can listen in on foreign officials half a world away. (graphic: Popular Mechanics)

Image: popular%20mechanics%201%2025%2012%20digital-spies.jpg