From Charles Grant, the Center for European Reform: The Libyan operation has shown that the US now expects Europe to look after its own backyard. The Europeans should be better prepared for the next time that they have to manage a military operation without NATO’s full involvement. The EU has a track record of running policing, peacekeeping and rule-of-law operations in many parts of the world. But it will never run a serious combat mission when all 27 are in charge. Provisions in the Lisbon treaty allows for ‘permanent structured co-operation’, the creation of a sub-group of militarily capable countries. But EU governments have not wanted to implement these provisions, because they are legally complex and do not define the entry criteria; governments disagree on what the criteria should be.

So Britain and France should establish a different sort of avant-garde, to provide Europe with the means to deploy military power. They should invite militarily serious member-states to join them in regular meetings. This club would work closely with the EU without being a formal part of it, rather like the ‘Schengen group’ before its integration into the Union. The club should not have a permanent membership because the countries wanting to take part would vary from occasion to occasion. Italy, Spain and Belgium sent fighters to Libya but would probably opt out of an operation in, say, Transnistria. But Poland, which shunned Libya, would probably join a mission to the east.

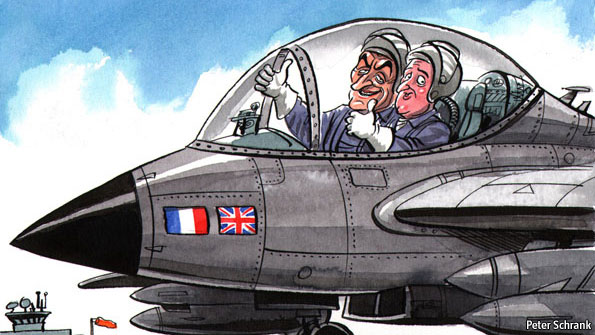

Britain and France would be the only permanent members and the leaders. They have the most powerful military capabilities in Europe and similar strategic cultures, based on an interventionist philosophy. Linked by two defence treaties, they are learning to work together on issues such as aircraft carriers and new military technologies. …

Some of the countries outside this military avant-garde would resent its existence. But they should recognise that a Union of 27 is not well-suited to conduct a shooting war, and that the US cannot be relied upon to fight wars on behalf of Europe. That means the Europeans have to take more responsibility, though not necessarily through the Union. NATO sometimes works with 28 members (though during the Libyan crisis Turkey delayed some key decisions). When it works it does so because the US leads and cajoles the others. Within Europe, a tight Franco-British alliance needs to give that kind of leadership.

Those excluded should emulate Britain’s response to the rise of the Euro Group: it welcomes more integrated economic policy-making among the 17, so long as it does not have to take part. Germany and other pacifistic member-states should take a similarly constructive attitude towards any Franco-British scheme to boost Europe’s military power.

Charles Grant is director of the Centre for European Reform. (graphic: Peter Schrank/Economist)

Image: economist%203%2024%2011%20Sarkozy%20Cameron%20in%20jet.jpg