From Stephen Fidler and Alistair MacDonald, the Wall Street Journal: Europe’s strapped militaries are looking for ways to cooperate with one another to compensate for cutbacks. But past efforts on that front have run into difficulties. Joint-procurement projects have been tripped up by national rivalries and domestic politics. One early effort to join ground forces, a Franco-German army brigade created in the late 1980s, has never been deployed in combat, in part because the two countries have contrasting views on the use of force. . . .

The Netherlands has whittled its defense budget from 1.6% of gross domestic product in 2006 to an expected 1.15% by 2015, according to IHS Jane’s. Rob de Wijk, a former Dutch defense adviser, told the Netherlands’ Parliament in May that the country’s military spending had fallen too far and the Dutch were now just "international freeloaders" on defense. He says the response he got from politicians left him with the impression that "they just didn’t care."

The Dutch have the equipment necessary for projecting power overseas: F-16 jets, submarines, air refuelers, frigates, surveillance capabilities and heavy-lift helicopters. But the numbers aren’t sufficient, says Mr. de Wijk, to keep operations going for more than short periods. A spokesman for the Netherlands Ministry of Defence did not return calls seeking comment.

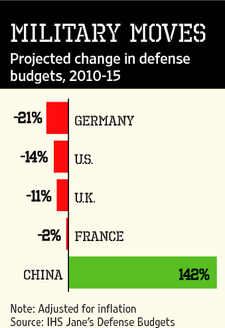

Defense-spending trends across Europe alarm Mr. Rasmussen, who became NATO’s civilian chief in 2009. "If you’re not able to deploy troops beyond your borders, then you can’t exert influence internationally, and then that gap will be filled by emerging powers that don’t necessarily share your values and thinking," he says. He didn’t specific any countries, but China is often mentioned in this context.

Mr. Rasmussen says one answer is what he calls "smart defense." Cooperation among countries in buying defense equipment, in training and in military exercises, he says, can deliver better value for the money. Countries also can specialize in certain military tasks. He wants that issue at the top of the agenda for NATO’s next summit in Chicago next year.

"Instead of pursuing purely national programs, we get more bang for the buck if we pool and share resources," he says. He has identified what he calls 10 critical capabilities, including the strategic airlifting of troops and equipment, intelligence gathering, drone technology and ground surveillance.

NATO already has done some pooling. Twelve countries cooperated to buy three C-17 air transports for carrying troops and equipment. Two NATO Airborne Warning and Control aircraft, staffed by multinational crews, have helped to coordinate air operations over Libya. . . .

Mart Laar, defense minister of Estonia, one of the few countries increasing its defense spending, contends that the future for European defense lies with shared procurement and pooling resources. Recently, Estonia and Finland—which doesn’t belong to NATO—bought 12 Thales-Raytheon radar systems, which meant that Estonia effectively got two radars for the price of one, says Mr. Laar.

Denmark, whose contributions in Libya were praised by Mr. Gates, already specialized its armed forces five years ago, giving up on submarines, other parts of its navy and some radar systems. With respect to submarines, "somebody is doing it smarter than we are, so we will rely on somebody else in NATO," says Danish defense minister Gitte Lillelund Bech. . . .

The Netherlands and Belgium have been cooperating for years, and they share a navy headquarters. The Netherlands is talking to Germany about the joint production of ammunition. Britain and France, which have similar views about the use of force, last year vowed to form a joint expeditionary force, share some equipment and cooperate on developing military technology. . . .

There is skepticism, nonetheless, that much will change, particularly given what happened in the past. British and French efforts over the past decade to cooperate on building aircraft carriers foundered, in part because they couldn’t agree on designs. In 1999, the U.K. pulled out of a project with France and Italy to build warships. A missile-defense project involving Germany, Italy and the U.S., now in the development phase, has so far failed to secure financing from Berlin and Washington for production.

Other European projects have been dogged by delays and cost overruns, including a four-nation consortium that built the Eurofighter, which was used by the British Royal Air Force over Libya, and an eight-nation project to build the A-400M military transport aircraft. Many European countries see no alternative but to cooperate on major projects, despite difficulties secure agreements among themselves. (graphic: Wall Street Journal)

Image: wsj%208%2024%2011%20defense%20spending.jpg