From Soner Cagaptay, the Bangkok Post: As Egyptians and Tunisians vote to replace ousted despots and the Syrian government teeters on the brink, two old imperial powers are competing to exert their political influence over Arab countries in upheaval.

And they are not America and Russia. After years of cold-war competition over the Middle East and North Africa, it is now France and Turkey that are vying for lucrative business ties and the chance to mould a new generation of leaders in lands that they once controlled. . . .

[O]ne thing has become obvious to the Turks: Paris won’t allow Turkey into the European Union or let it become a powerful player in a French-led Mediterranean region.

Turkey’s newly activist foreign policy has therefore shifted away from Europe. The ruling Justice and Development Party, known as the AKP., is now cultivating ties with former Ottoman lands that were ignored for much of the 20th century. Of the 33 new Turkish diplomatic missions opened in the past decade, 18 are in Muslim and African countries.

This has resulted in new commercial and political ties, often at the expense of Turkey’s ties with Europe.

In 1999, the European Union accounted for over 56% of Turkish trade; in 2011, it was just 41%. Over the same period, Islamic countries’ share of Turkish trade climbed to 20% from 12%. . . .

As France’s business ties with the old secular elite fray, its influence is waning.

It remains a military and cultural power, and will continue to attract Arab elites, even Islamist ones, seeking weapons and luxury goods. However, France will find it hard to market its brand of secularism across the region or match Turkey’s grass-roots business networks, especially in Syria, Lebanon and Iraq, where Turkey already has significant clout.

Even so, the road ahead will be rocky. Turkey ruled the Arab Middle East until World War I, and it must now be careful about how its messages are perceived there.

Arabs might be drawn to fellow Muslims, but like the French, the Turks are former imperial masters.

Arabs are pressing for democracy, and if Turkey behaves like a new imperial power, this approach will backfire.

At a recent conference at Zirve University, a gleaming private school in Gaziantep financed by the local businesses that have made Turkey a regional economic powerhouse, Arab liberals and Islamists from various countries disagreed on most matters but agreed on one thing: that Turkey is welcome in the Middle East but should not dominate it. . . .

Turkey may have the upper hand in soft power, but France has more hard power, as the recent war in Libya and its veto power at the United Nations make clear.

And despite Turkey’s phenomenal growth since 2002, the French economy is more than twice the size of Turkey’s, and France is still dominant in North Africa.

Turkey’s relative stability at a time when the region is in upheaval is attracting investment from less-stable neighbors like Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. Ultimately, political stability and regional clout are Turkey’s hard cash, and its economic growth will depend on both.

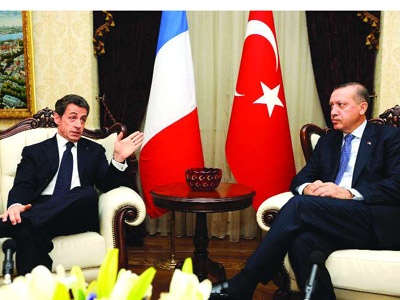

Soner Cagaptay is a senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. (photo: Dünya Bülteni) (via Real Clear World)

Image: dunya%20bulteni%201%2017%2012%20Sarkozy%20Erdogan.jpg