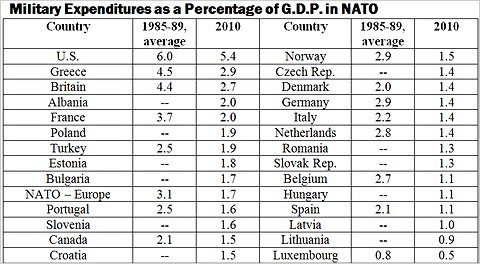

From Gulliver, Ink Spots: [I]t happens that in a decade of unprecedented global military expenditures and increased operational tempo and warfighting demands on Western countries, the point of highest average proportional spending by the relevant sub-groups was in 2001 — prior to the start of those operations!

I alluded to this above, but you should also take note of the fact that the Non-U.S. NATO figures are a few percentage points below the European NATO figures across the board… meaning that Canada’s thriftiness is dragging the purportedly stingy Europeans down. . . .

Considering the popular wisdom about which allies are and are not pulling their weight in NATO, I think many people will be surprised to see this graphic. Of course, some analysts have perceived the not-so-subtle shift in new member states’ priorities over the last several years. But here’s the proverbial picture worth a thousand words: the former Eastern bloc countries have consistently contributed a smaller share of GDP, on average, to their defense over the last decade. As coalition operations in Afghanistan ramped up in the latter part of the 2000s, the traditional allies held spending steady or made slight increases. . . .

The opposite is true of the former Eastern bloc countries, of which only Estonia and Albania (an aspiring and then brand-new member) aggressively increased their defense share. . . .

As Secretary Gates made clear before leaving office, worries about a two-tiered alliance no longer break down along the same lines as during the Bush administration, when the U.S. and its plucky new post-communist allies were thought to be eager for a fight in contrast with the staid and stingy Western Europeans. Instead the UK, France, Germany, Italy, and Norway have held military spending relatively steady as a percentage of GDP while many new NATO members have sought to cash in on the security dividend of Article 5 guarantees to redirect some spending away from defense programs. These trends should have been predictable: after all, it was certainly in the interest of NATO aspirants to dedicate extra resources to defense for a time in order to achieve vital diplomatic (and by consequence, strategic) effects, while the military expenditures of traditional allies will have settled at their current levels through iterative analysis of defense requirements and other governmental spending priorities. Over the next decade, I’d expect we’ll see the same phenomenon occur with the new allies, and barring unexpected surge requirements (which, of course, we can’t do), spending/GDP ratios should be reasonably stable and settled across the alliance. Maybe Albania and Estonia will continue to increase spending and outstrip their similar neighbors, but probably not.

Proportional defense spending obviously isn’t the only indicator of commitment to the Alliance’s health and well-being, and it would be unfair to dismiss the contributions of Canadian, Polish, and Dutch soldiers (and Estonians, for that matter) just because of unimpressively average budgetary contributions. But it’s certainly interesting to see how the numbers don’t exactly sync with popular expectations. (graphic: NATO/New York Times)

Image: nato%207%2015%2011%20defense%20budgets%20GDP_0.jpg