From Mark Landler, the New York Times: At home in France, he has long been called “Sarko l’Américain. ” But it took an American president and the threat of a massacre in Libya to give President Nicolas Sarkozy the chance to channel his inner American. With his call for military action against Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi, his recognition of the rebels and his readiness to arm them, Mr. Sarkozy has looked every inch the swaggering world leader, less a latter-day Charles de Gaulle than a Gallic Ronald Reagan.

For President Obama, too, Mr. Sarkozy has been an enabler, but of a different sort. By thrusting France so far out front, he has allowed Mr. Obama to claim credibly that Libya is now a model of multilateral cooperation, not merely the third Muslim country the United States has gone to war with in the last decade. Pulled reluctantly into the conflict by the urgent pleas of European and Arab leaders — none of the pleas more urgent than Mr. Sarkozy’s — Mr. Obama has managed to sound almost European.

It is an unlikely geopolitical Alphonse-and-Gaston routine, featuring two men who are outriders in their own political landscapes and who have each taken a risk by going against the conventional wisdom in Paris and Washington. But the routine also has broader implications because it augurs a world in which the United States, militarily stretched and fiscally depleted, can no longer afford to play global policeman alone.

“It would be tempting to say Sarkozy the American is encountering Obama the European, but it would be wrong,” said Dominique Moïsi, the founder of the French Institute for International Relations, who helped popularize the nickname “Sarko l’Américain.” For these two very different leaders, “this is a marriage of convenience. …”

“The Europeans keep saying, ‘We’re ready to lead, we’re ready to lead, we’re ready to lead,’ ” said Anne-Marie Slaughter, a former policy planning director at the State Department who now teaches at Princeton. “Finally, we’ve found a Frenchman willing to step into the role. …”

For Mr. Sarkozy, there are huge risks to all these adventures. Libya could slip into a stalemate between the rebels and Colonel Qaddafi’s forces. Having recognized the rebels early as legitimate rulers of Libya could boomerang, given how little the West knows about them. Mr. Sarkozy could face the wrath of voters if the United States is viewed as having shifted too much of the burden to France.

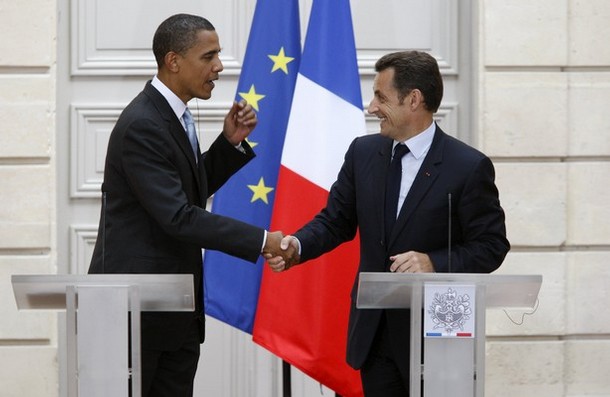

There are dangers for Mr. Obama, too. Critics in Congress say he has thrown the United States into a mission with an ill-defined goal. For all his talk about partners and burden-sharing, the American military still constitutes the bulk of NATO’s fighting force, and as such, is essential in the operation. Without Mr. Obama as his wingman, Mr. Sarkozy would lose much of his swagger. Then, too, the idea of a military operation not led by the United States does not sit well with some Republicans. (photo: Reuters)

Image: obama-sarkozy.jpg