From David Owen, the Telegraph: Paradoxically, it is Nato rather than the UN that emerges battered and divided from the intervention. Only eight of its 28 members – less than one third – agreed to engage their air forces and bomb Libya. Britain and France bore the brunt of the work, flying over Libya day in, day out. Italy, the old colonial power, did make airfields available, and was broadly supportive. Canada and Norway also contributed. Yet Germany, the most powerful country in Europe, was opposed to intervention, and refused to become involved. Poland was not ready to engage. Turkey and Spain refused to fly attack missions. What was even worse for Nato’s self-esteem, however, was its demonstrable incapacity. Robert Gates, the outgoing US defence secretary, did not mince his words when he said in his farewell speech in Brussels in early June: “The mightiest military alliance in history is only 11 weeks into an operation against a poorly armed regime in a sparsely populated country – yet many allies are beginning to run short of munitions.”

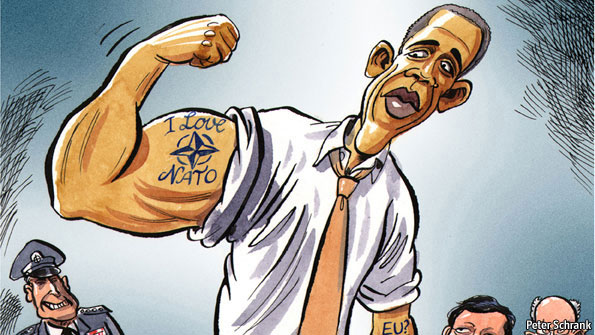

Does this mean, therefore, that Nato is no longer fit for purpose? Not exactly. For all its limitations. it did provide the crucial infrastructure needed for command and control, covering the three essential forces – US, French and British. The campaign proved that Franco-British military co‑operation, which is becoming a cornerstone of both countries’ defence strategy, can and does work – a huge lesson, and a huge relief, for both London and Paris. These two countries, and these two alone, provide the core of Europe’s defence capability. Yet we have also learned that we still rely enormously on the US, and need to operate jointly with them – and that, in effect, means Nato should continue. . . . (graphic: Peter Schrank/Economist)

Image: economist%2011%2030%2010%20EU%20NATO%20envy_0.jpg