From Charlemagne, the Economist: A new report by a group of prominent economists—sponsored by Jacques Delors, the former president of the European Commission, and Helmut Schmidt, the former German chancellor—describes in telling detail how the euro is destroying itself.

Start with the European Central Bank’s “one size fits all” interest rate, which the report’s leading author, Henrik Enderlein of the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, relabels a “one size fits none” rate. Differences in inflation are magnified: in countries with higher-than-average inflation (eg, Italy), the real interest is too low, fuelling more inflation; the opposite is true in countries where inflation is low (eg, Germany). Another problem is that the single market is far from complete, so that competition does not even out price differences across the EU. The market in services, which represents the biggest share of economic output, is still fragmented. Moreover, European workers are less likely to move in search of jobs than, say, American ones. A further curse is that countries of the euro zone do not independently control their own money. Because each lacks its own central bank to act as a lender of last resort, troubled countries can more easily be pushed into default as markets panic. Lastly, cross-border financial integration has spread far enough to channel contagion from one country to another, but not so far as to break the cycle of weak banks and weak sovereigns bringing each other down.

These shortcomings have now become painfully familiar. Some of them were known when the euro was created. Mr Delors himself, in a seminal report of 1989 launching the process of monetary union, warned about the dangers of economic imbalances and the risk that states could be shut out of bond markets. Yet the dangers were for the most part ignored, or reckoned to be manageable through fiscal rules and the promise of economic convergence. Those who saw trouble in store thought a crisis would provide the impulse for greater integration in future. . . .

The hope of forging a common European identity has given way to greater national assertiveness, even chauvinism. Anti-immigrant and anti-EU parties are gathering strength. . . .

Economic logic dictates that the euro zone must become more federal, sharing banking risks and issuing debt jointly. Political reality, however, works against this. European treasuries are still national, as is politics. For creditor nations, “more Europe” could come to mean paying the debts of unworthy foreigners; for debtors, it could mean having foreigners intruding ever deeper into their affairs. . . .

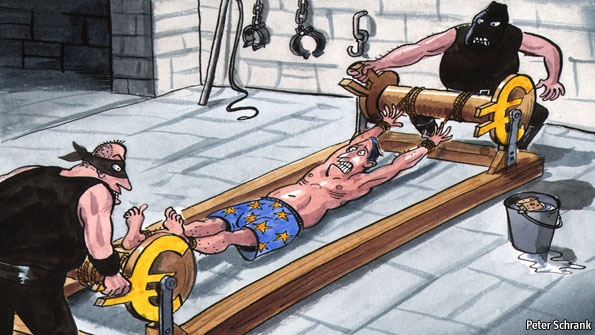

Can the euro zone survive the rack for that long? Perhaps the pain will be such that citizens and leaders will look to integration for relief. The danger is that, if the torture goes on, the European project will expire first. (graphic: Peter Schrank/Economist)

Image: economist%207%206%2012%20Euro.jpg