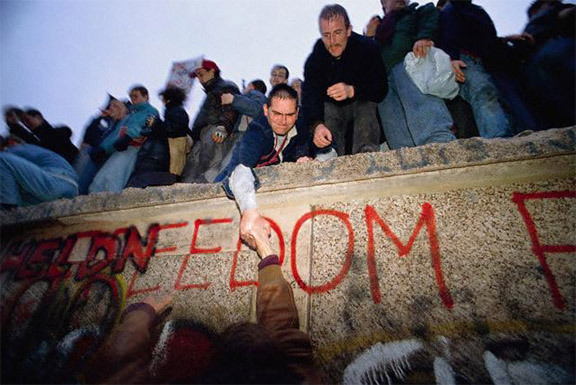

Twenty years is not a very long time in history but the fall of the Berlin Wall already seems like another era. The euphoria, confidence and excitement that accompanied that event were overtaken in short order by cynicism, fear and doubt resulting, according to some quarters at least, from American triumphalism.

Despite the new leaf that Barack Obama’s election appears to have turned over, it will be a long time before the world hears the United States speaking of itself again as the “indispensable nation” or the American way of life as the harbinger of the end of history.

This has also been called the beginning a “new” era of globalization. But 1989 was mainly about Europe. Nobody should forget the tanks and bullets that appeared in Beijing that very same year.

In truth, 1989 represented a culmination more than a new departure. It marked the final end of a long European civil war, the third since 1914. To some it was the apotheosis of a very long campaign for continental unity, George H.W. Bush’s “Europe, whole and free.”

To many Americans, Bush’s statement rang true. Not only because of their own history of e pluribus unum, but also because the European project — and America’s critical role in it — had much to do with Americans’ sense of themselves as transplanted Europeans, eager to prove to the so-called Old World that it could master its diplomatic ways.

But in the end, both Americans and Europeans realized there was much they could teach one another.

Nothing like this relationship exists elsewhere in the world, least of all in its most contentious regions. Like the once great powers of Europe, the United States has long played a powerful role in the Middle East and Northeast Asia, going back to the days of the Barbary Pirates and Commodore Perry’s Black Ships, but in an itinerant and episodic fashion.

Asian civilization does not carry the same cultural significance for most Americans that European civilization once did. An “Asia whole and free” is not a phrase we expect to hear any time soon from an American president.

This is a terrible pity because it seems the lessons of the 20 century learned in Europe are bound to be forgotten.

Namely, that there is no such thing as a permanent rivalry among nations; that neighbors, whatever the obstacles, can be partners; that zero-sum relationships can be the exception, not the norm; that peace is forged both from the top down and from the bottom up; and that global issues — like the environment, crime, trade — are best handled in a regional framework with institutions that promote good neighborliness while at the same time setting higher standards for others to emulate.

For Americans, in particular, a good deal of Europe’s success came down to trusting Europeans and letting them take much of the credit.

It may have taken a half-century of immense destruction at the hands of Europeans to transform the above into axioms that few challenge today. But, again, this is mainly the case in Europe and America.

The West, as it was once proudly called, has come to seem more and more like an island rather than a beacon. Along its peripheries, even just next door, are frightening echoes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The response of most Europeans and Americans to them has been, sadly, one of limited liability. Most spent the 1990s cultivating their own gardens; so far, much of the following decade has been spent building new walls or in being consumed by the passions of the moment.

The world of 2009 is still much freer, more open and more peaceful than the one of a generation ago. But how much longer can this last?

As the zeitgeist of 1989 recedes into distant memory, we should do all we can to keep alive the promise it once represented.

Kenneth Weisbrode is a historian at the European University Institute and author of “The Atlantic Century.” This essay was previously published by the

.

Image: Berlin%20Wall%20Freedom_0.jpg