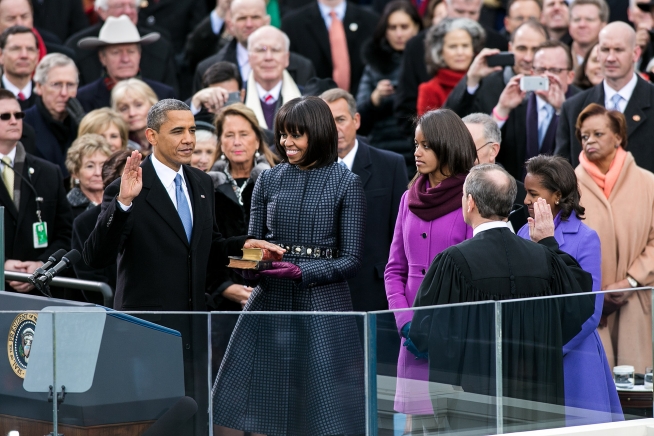

In his second inaugural address, President Obama offered these thoughts on winding down an age of conflict: “Enduring security and lasting peace do not require perpetual war.” And, he continued, “We will show the courage to try and resolve our differences with other nations peacefully – not because we are naive about the dangers we face, but because engagement can more durably lift suspicion and fear.”

These are noble aspirations, and one is drawn to sympathize with them. But do they really fit the world we live in today? The assumptions behind these sentiments seem to be (a) that the United States has differences with other nations and chooses to resolve them either by force or by peaceful means; (b) other nations view the US with suspicion and fear, which we should dispel; and (c) that if the US does not engage in perpetual warfare, there will be peace.

In the world of 2013, such assumptions sound off-key. Today’s conflicts have little to do with American differences with other nations, or fear and suspicion of the US. For example, the conflict in Syria – where the US has studiously avoided engagement – is driven by a despot willing to kill more than 60,000 of his own citizens (and counting) in order to cling to power. Those citizens seek to protect themselves, fight back, and topple the dictator, yet they receive little US or Western support.

Similarly, the war in Afghanistan is internally focused. It started because Al Qaeda used Afghan territory to plot the 9/11 attacks, but today’s conflict is based on the Taliban seeking to overthrow the Afghan Constitution and the elected government in order to re-impose their own harsh rule. US engagement is aimed at helping Afghan authorities become strong enough to fend off continued attacks from the Taliban and stand on their own (and thus prevent terrorists from again using it as a launchpad).

Indeed, the greatest risks to peace and security today – for the US and the world – seem linked with too little US involvement, rather than too much. Following America’s withdrawal from Iraq, violence – and the risk of even greater conflict – has increased. After the overthrow of Muammar Qaddafi in Libya, the new authorities struggled on their own to gain control of weapons and militias in the country – with the result that Islamist militants were able to carry out the attacks in Benghazi that killed four Americans, while other jihadists – as well as arms – crossed into Mali.

When France stepped in to prevent the extremists taking over the entire country of Mali – and thus gaining all the territory and economic resources that would imply – militants then attacked a gas facility and took dozens of hostages in Algeria last Wednesday. Algerian forces then stormed the plant allowing hostages to escape. In all, 38 hostages and 29 militants were killed in the standoff and chaos, with five hostages still unaccounted for.

One can surely understand the fatigue felt in the US and Europe at the loss of life and treasure in far-off lands. The temptation to pull back and focus on “nation-building at home” is strong. Few in US see these regional conflicts as America’s problems. No one wants the US to be a global policeman.

Yet as France continues to take the lead in preventing the collapse of government and creation of a terrorist-controlled state in Mali, leaders in Washington and the capitals of Europe should consider the wider implications of this alarming conflict (in addition to providing more robust assistance). The absence of US leadership creates a vacuum that dangerous elements actively exploit – ultimately harming American and global security.

Mr. Obama is right to suggest that the best solutions to such conflicts are not military. It is both safer and cheaper to protect our interests through more substantial and proactive support for democracy, reform, and local security, than it is to wait until the risks are so great that military intervention is necessary. But when it gets to the point that extremists are using force to impose their own will, force may become necessary to stop them. And indeed, the credible use of force becomes a deterrent to further conflict down the road.

For more than two years, people in the broader Middle East and North Africa have been on an unprecedented journey – demanding greater democracy and justice in society, instead of the Hobson’s choice between secular tyrants and Islamist dictatorship. As events in Egypt, Syria, Libya, Mali, and Algeria all show, there are enormous risks in this transition. Yet with the genie now out of the bottle, there is no turning back.

Moderates and reformers in these regions need far more substantial assistance from Western democracies in maintaining security and delivering on democratic and economic reform. The US and other democratic nations have a direct interest in providing this assistance. It is the failure to exercise such leadership, instead leaving a vacuum for extremists to fill, that provides the greatest risk of conflict in the world of 2013.

Kurt Volker, a former US ambassador to NATO, is executive director of the McCain Institute for International Leadership, a part of Arizona State University, and a member of the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Advisors Group. This piece first appeared on The Christian Science Monitor.

Photo credit: The White House

Image: p012113sh-0576_0.jpg