Though ostensibly a tool to pause fighting between regime and rebel forces in Syria, the latest ceasefire attempt on February 26 collapsed in less than two hours. This was in fact a Russian-supported “humanitarian pause,” intended to last five hours and allow aid to reach the besieged inhabitants of the Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Damascus. Five hours proved to be not enough time for aid workers to carry out the mission, and too much time for combatants to stop fighting.

Though ostensibly a tool to pause fighting between regime and rebel forces in Syria, the latest ceasefire attempt on February 26 collapsed in less than two hours. This was in fact a Russian-supported “humanitarian pause,” intended to last five hours and allow aid to reach the besieged inhabitants of the Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Damascus. Five hours proved to be not enough time for aid workers to carry out the mission, and too much time for combatants to stop fighting.

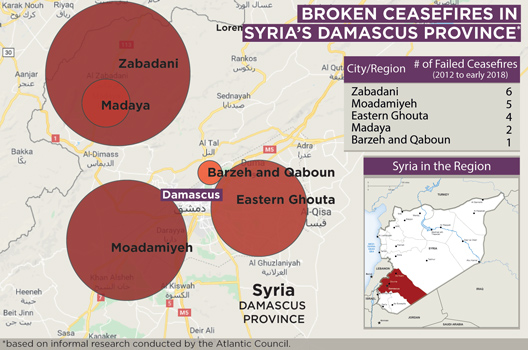

Prior to this measure, the United Nations (UN) Security Council (and therefore Russia) had approved a longer, more ambitious thirty-day ceasefire after the ongoing regime offensive on Eastern Ghouta caused over five hundred deaths in one week. That ceasefire cannot really be said to have broken down because it never took hold in the first place.

There are a few key reasons why all the ceasefires, de-escalation agreements, humanitarian pauses, and cessations of hostilities eventually collapse in Syria.

One of the main downfalls to any ceasefire attempt is the regime’s outlook on the war, namely, the fact that it does not recognize the legitimacy of any opposition that challenges its political monopoly over Syria. Rather, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad views these challengers as traitors to the nation, fools tricked into believing their cause is just, or sectarians out to subjugate the Alawite sect. Assad believes absolute control over all of Syria is the only way to subdue and deter such challengers. Such a view of the conflict necessitates that rivals be destroyed or reintegrated into the very regime structures against which they rebel.

If this is Assad’s frame of reference, it would be irrational for the international community to expect the regime to respect ceasefires that would normalize the presence of opposition groups in crucial territory such as the Damascus suburbs. Further, the regime has successfully used collective punishment, namely in Aleppo, to subdue densely-populated, built-up, opposition-held areas, bombing rebels and civilians alike. This strategy makes it illogical for Assad to allow humanitarian aid or evacuate the ill and injured, as often mandated by ceasefire agreements. Making these concessions when the regime enjoys its current overwhelming military advantage over its rivals would make very little sense.

It is impossible to convince the Assad regime that Syria can or ought to be shared with hostile armed groups, especially without the credible threat or use of force—and perhaps with it as well.

In the absences of ceasefires imposed by force, the regime will continue to opt for military victories whenever possible. Where they prove elusive, the regime will treat this as a temporary obstacle to be revisited at a more opportune time, perhaps after weaker areas are subjugated or resources freed up from other battles. That has been its pattern throughout the war, in which cessations of hostility are used to free up regime resources to fight on more urgent or more promising frontlines.

After seven years of war, Western policymakers and diplomats still seem unable to grasp basic truths about the situation in Syria. Having rightfully condemned the regime for its atrocities, these actors fail to see the war through Assad’s eyes. Consequently, those in Washington and Brussels continue to expect the regime to behave in ways that undermine its own interests and contradict its understanding of the war. Alongside this myopic view, the West continues to place substantial faith in Russia’s willingness and ability to curb regime excesses and secure lasting, meaningful ceasefires, and cessations of hostility. Russia has indeed backed a number of these initiatives, yet it is Assad who decides whether they hold. All he has to do is break a ceasefire in order to impose new realities on all other parties. Since so few have, one (or both) of two things is true:

The explanation least charitable to Russia is that it supports continued regime violations even as it strings western governments along in diplomatic initiatives. The Kremlin does so by distracting international rivals, projecting respectability as a responsible member of the international community, and buying time for the Assad regime to complete its reconquest of Syria. Based on the situation on the ground in Syria, this strategy, based on a combination of Russian cynicism and masterful execution, it appears things have gone exactly to plan.

However, it is also possible that Russia would like the Kremlin-backed ceasefires to hold, allowing Russian President Vladimir Putin to demonstrate his political clout. Russia does not need Assad to reconquer all of Syria, but it cannot compel the regime to jeopardize its own core strategic interests by abandoning its commitment to doing so, despite its military support for Assad.

There is probably a combination of Russian deception and limits on its influence over Assad at play. Yet both Western observers and Syrian opposition members and supporters have tended to minimize Assad’s agency in Syria, and to view him as a puppet or dependent of Russia. It is true that he would not have survived without Russian help, but how would that give Russia the ability to coerce him into ceding parts of his country to mortal enemies? Would Russia withdraw its military support, thereby allowing Assad to be defeated? Would it abandon its entire platform of support for Syria’s government, the entire rationale for having intervened in the first place?

Since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2012, the only successful cessations of hostilities have been instated in the wake of the regime’s thorough crushing of armed opposition groups, and sometimes the forced displacement of local populations. This is because the regime only accepts lasting ceasefires after it has already won. Rebel groups know this, which is why they accept ceasefires to prolong their survival and, for local groups, the safety of the local population. The Syrian regime also knows this, which is why it ultimately abandons ceasefires for a military solution to the problem of stubborn opposition holdouts.

Not only will there be no lasting ceasefire in the Eastern Ghouta, but other opposition holdouts thus far spared by Russian-supported “de-escalation agreements” such as those in southern Syria will be attacked after Eastern Ghouta falls.

The Syrian war is complex and presents fiendish policy challenges, but the futility of ceasefires is easy to understand. What is odd is that Western governments continue to embrace a strategy that bets on Russian goodwill and regime irrationality. There are only three ways to end hostilities in opposition-held parts of Syria: external powers would need to impose a stalemate by rectifying the severe imbalance of power between regime and opposition, intervene militarily against the regime, or let the fighting end with total regime victory on Assad’s terms. Any other approach, such as an endless cycle of ceasefires, is more likely to further expose Western superficiality and incompetence, and prolong the suffering of Syrians.

Faysal Itani is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. You can follow him on Twitter @faysalitani.

Image: A woman pushed a stroller past damaged buildings in the rebel-held besieged city of Douma, in the eastern Damascus suburb of Ghouta, Syria, on January 8, 2017. (Reuters/Bassam Khabieh)