General Stanley McChrystal’s widely-publicized comments deriding senior Obama administration officials and their roles in the Afghanistan strategy have, as he himself has acknowledged, "compromised the mission." He’s meeting with said team this morning and could well be fired. Regardless, it’s time to come up with a unified and coherent policy.

The controversy has certainly refueled the debate, with administration critics coming out in droves.

In the midst of a WSJ op-ed arguing that McChrystal must be sacked despite being "a selfless, fearless and inspiring soldier" and "something of a military genius," former State Department counselor Eliot Cohen argues,

The Obama administration has made three large errors in the running of the Afghan war.

First, it assembled a dysfunctional team composed of Gen. McChrystal, Amb. Karl Eikenberry and Amb. Richard Holbrooke—three able men who as anyone who knew them would predict could not work effectively together. Mr. Eikenberry was a former commander in Afghanistan, junior in rank to and less successful than Gen. McChrystal, and had very differing view of the conflict. Mr. Holbrooke, a bureaucratic force of nature, inserted an additional layer of command into a fraught set of relationships. As a stream of leaks has revealed, the staffs loathe each other.

The second error lies in the excruciating strategy review of last fall. Internal dissension spilled into public, making it clear that Vice President Joe Biden took a very different view of the war than the Defense Department and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. The competitive leaking, sniping and bickering that pervaded the review worsened the climate of command and undoubtedly left Gen. McChrystal and his team unnerved.

The third, and fatal, error came in Mr. Obama’s West Point speech in December. He put his own ambivalence about the Afghan war on public view and then announced that he would begin a withdrawal in July 2011. This blunder demoralized his own side while elating the enemy and encouraging Afghan friends and neutrals to scramble to make their accommodations while they could.

WaPo columnist Jackson Diehl, who argues that McChrystal should be retained because firing him "could spell disaster for the military campaign he is now overseeing in southern Afghanistan, and it would reward those in the administration who have been trying to undermine him, including through media leaks of their own," likewise thinks it’s time for the administration to get things right.

[T]he tensions McChrystal disclosed were not news to anyone who has been following the Afghanistan mission in recent months; I first wrote about them more than a month ago.

Nor is McChrystal the only participant in the feuding who has gone public with his argument. A scathing memo by Eikenberry describing Karzai as an unreliable partner was leaked to the press last fall. At a White House press briefing during Karzai’s visit to Washington last month, the ambassador pointedly refused to endorse the Afghan leader he must work with.

Biden, for his part, gave an interview to Newsweek’s Jonathan Alter in which he said that in July of next year “you are going to see a whole lot of [U.S. troops] moving out.” Yet as Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates tartly pointed out over the weekend, “that absolutely has not been decided.” Instead, Biden was pushing his personal version of the strategy Obama approved, which calls for the beginning of withdrawals next year, with the size and pace to be determined by conditions at that time.

The real trouble is that Obama never resolved the dispute within his administration over Afghanistan strategy. With the backing of Gates and the Pentagon’s top generals, McChrystal sought to apply to Afghanistan the counterinsurgency approach that succeeded over the last three years in Iraq, an option requiring the deployment of tens of thousands more troops. Biden opposed sending most of the reinforcements and argued for a “counterterrorism plus” strategy centered on preventing al-Qaeda from establishing another refuge.

Senator John McCain, who of course lost to Obama in the last presidential election, adds:

"If the president fires McChrystal, we need a new ambassador and we need an entire new team over there. But most importantly, we need the president to say what Secretary Clinton and Secretary Gates have both said but what the president refuses to say: Our withdrawal in the middle of 2011 will be conditions based. It’s got to be conditions based and he’s got to say it."

AEI’s Thomas Donnelly and Weekly Standard editor William Kristol agree:

So McChrystal should not be the only one to go. Ambassador Karl Eikenberry and “AfPak” czar Richard Holbrooke should likewise either submit their resignations or be fired by President Obama. Vice President Biden and his surrogates should be told to sit down and be quiet, to stop fighting policy battles in the press. The administration’s "team of rivals" approach is producing only rivalry.

Most of all, the commander-in-chief must take command. Barack Obama’s commitment is famously and publicly uncertain. No one—not his lieutenants, nor his cabinet, nor his generals, nor the American people, nor our allies, nor the Afghans, nor our enemies—can be sure whether the president wants to win the war or just to end the war.

The McChrystal contretemps creates an opportunity to right many of these wrongs; the White House should not waste this crisis. Anything less than a clean sweep will leave the war effort impaired.

Ordinarily, I wouldn’t base an entire piece around the views of Republican critics, especially when they’re all neoconservatives and naturally opposed to the administration’s policies. But I agree with their criticisms despite having thought for two years or so that we’ve accomplished all we can reasonably expect to accomplish in Afghanistan and should head for the exits. Thus, these criticisms of the administration’s process ring true despite my policy preferences being closer to the administration than to these critics.

As regular readers of this space know, I’ve been quite critical of the administration’s Afghanistan policy since they began its rollout. First, they rolled out a "new" strategy that wasn’t new. Then they fired a perfectly competent commander to put in their own man, McChrystal, to implement a counterinsurgency policy. Then, after he submitted his plan, they spent weeks publicly hemming and hawing over it, not only leaving Allies twisting in the wind but leaving us wondering why they installed McChrystal if they weren’t going to follow the strategy he was specifically chosen to implement. Then, they announced a bizarre compromise solution that included a troop surge, approval of a counterinsurgency military strategy, a political strategy that called for mere counterterrorism and development, and a timetable that allowed for neither.

And, as WaPo’s Anne Kornblut notes this morning, the jockeying between McChrystal and Vice President Biden, who represent the opposite poles in the internal debate, has continued well after the decision was announced.

My takeaway from all this was that President Obama had come to believe, as had I, that the very ambitious set of goals articulated by his predecessor were unattainable but that he believed saying that was politically untenable. Since he had campaigned on Afghanistan as a "war of necessity" that the Bush administration had under-resourced to pursue a "war of choice" in Iraq, he couldn’t very well say, mere months into his term, that Afghanistan wasn’t worth it after all. Further, bugging out before the job was done would lead to charges of weakness that no president, particularly a Democratic president with no military bona fides, wants to fight.

Presuming that McChrystal is going to go at this point, that means yet another change of generals and, necessarily, at least some change in strategy. That’s unfortunate given that there’s very little political will left in the United States and the other NATO countries for this war. But it does provide yet another opportunity for the president to decide what it is he wants to accomplish in Afghanistan and what resources he’s willing to put into it. The two should mesh.

Further, the critics are right: Whatever the ultimate plan, the key players have to be on the same sheet of music. So pick people committed to the president’s agenda, whatever that may be.

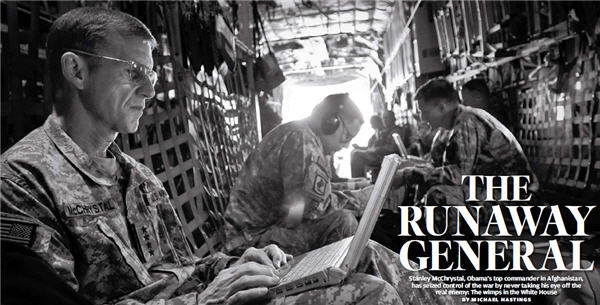

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council. Image: Rolling Stone.

Image: mcchrystal-runaway-general.jpg