When Chinese negotiators reportedly walked back some of their commitments to structural changes within the framework of a US-China trade deal late last week, US President Donald J. Trump threatened to increase tariffs on Chinese imports from 10 percent to 25 percent despite ongoing negotiations — a threat that became a reality at midnight on May 10. China announced retaliatory tariffs and Trump said he would impose tariffs of 25 percent on $325 billion in Chinese imports to the United States that are not currently taxed if there is no trade deal within the next few weeks. Trump’s focus could next shift to a different front: a May 18 deadline to decide on how to react to a US Commerce Department report — a decision that could result in tariffs on imported cars and car parts. How might this week’s developments impact his decision? And what does this mean for the prospect of commencing formal US-European Union (EU) trade negotiations?

Why car tariffs are a likelihood

After the European Council gave the green light to the European Commission to start negotiating with the United States on industrial goods (excluding agricultural products), and on removing burdensome conformity assessment requirements where feasible (removal of non-tariff barriers), EU trade representatives came to Washington earlier this week for another round of meetings with their US counterparts. However, the two sides have yet to launch formal negotiations, which have been held up by disagreements over the scope of a potential agreement.

There is a big incentive for the EU to keep open a dialogue: as long as conversations are ongoing, the Trump administration has agreed not to impose any further tariffs on the EU. Yet there are several reasons to believe that the Trump administration might reconsider its position toward Europe, especially in light of recent developments in its negotiations with China. These reasons include:

Chinese retaliation: US cars could be among the products that are hit by Chinese retaliation. In 2017, the United States sent about a fifth of its car exports (more than $10 billion worth of cars) to China. That number dropped to $6.6 billion after China put a 25 percent tariff on US car imports in response to US tariffs. The tariffs on US cars were lifted in December after the United States and China agreed to intensify trade negotiations. If China targets US cars in response to this week’s US tariffs, it might incentivize the Trump administration to impose tariffs on foreign cars and car parts in order to protect US manufacturers.

Expected European gains from US-China escalation: Recent UNCTAD analysis indicates exports from the EU may grow by as much as $71 billion as a consequence of the US tariffs on Chinese exports, replacing US and Chinese firms. Trump is likely to see this as a justification to raise car tariffs to rebalance a deepening trade deficit with the EU.

US focus on agriculture: Apart from structural changes to the way China conducts business, one of the focal points of the US-China trade negotiations is to significantly increase US agricultural exports to China. The new US tariffs and expected Chinese retaliation are likely to put additional strain on US farmers. This will increase the Trump administration’s desire to include agriculture in a potential trade deal with the EU — something on which the EU will not budge because some of its member states are dependent on agriculture and want to keep their markets shielded from more competition. Trump could use the threat of car tariffs on the EU to again try and put agriculture on the negotiating table.

Lack of progress: Tariffs are clearly a significant tool of the Trump administration’s trade strategy. If negotiations do not go to Trump’s satisfaction or take longer than anticipated, the administration threatens punitive measures. One of the reasons why Trump decided to increase tariffs on Chinese imports was because of a lack of progress in the negotiations. The same argument could be made for the EU.

US economic situation: Recent Q1 data show that the US economy is performing exceptionally well. This has emboldened the Trump administration to take drastic measures against China. The same logic could encourage the administration to favor car tariffs on May 18.

No window of opportunity for a transatlantic deal: The window to conclude transatlantic trade negotiations seems to have shut with European parliamentary elections coming up later in May followed by US elections in 2020.

How would tariffs affect companies and consumers?

Car tariffs would affect companies and consumers both directly and indirectly. In the immediate term, European cars in the United States would cost more. US companies that purchase cars and car parts outside the United States will have to pay the tariff and will (at least in part) pass these additional costs down to the consumer. Indirectly, companies and consumers on both sides of the Atlantic will lose out on the potential economic gains that would have resulted from a transatlantic agreement on industrial goods, and on conformity assessment, negotiations for which would come to an abrupt halt if car tariffs were to be announced. In contrast to China, which is continuing to negotiate with the United States despite the latest tariff increase, the EU has made it clear that should any further duties be imposed it would cease any negotiations with the United States and respond with retaliatory measures.

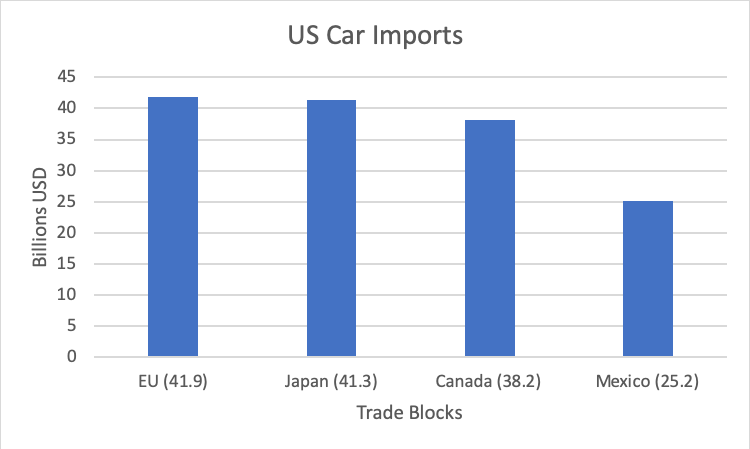

US Car Imports in 2018

Is all hope lost?

If the United States and China were to reach a deal Trump could feel empowered to be tough on Europe. He would be well-advised not to overextend his negotiators by opening up another front in a trade war.

There are plenty of options besides the “tariff” or “no-tariff” scenarios. These range from different timelines for different countries to delaying the decision to impose tariffs on a smaller list of countries. May 18 is an artificial deadline that Trump can extend by requesting further analysis on the economic impact of tariffs on the US economy or closing the current investigation and conducting another Section 232 investigation into the national security impact of the import of cars and car parts. He could also decide to give a 180-day exemption for countries that have ongoing trade negotiations with the United States (the EU and Japan) or offer affected countries to agree to export quotas to avoid further tariffs, as he did in the case of steel and aluminum tariffs. These temporary exemptions could be accompanied by a strict deadline by when deals with the EU and Japan would have to be reached.

Not imposing car tariffs would make sense economically and would be important for the United States’ China strategy. If the Trump administration wants to keep multilateral support to address Chinese trade practices at a global level, i.e. through a trilateral dialogue with the EU and Japan, Trump should not impose further tariffs on either of these partners—coincidentally the two biggest exporters of cars and car parts to the United States.

Marie Kasperek is deputy director of the Atlantic Council’s Global Business & Economics Program. You can follow her on Twitter @TheTradeShop.

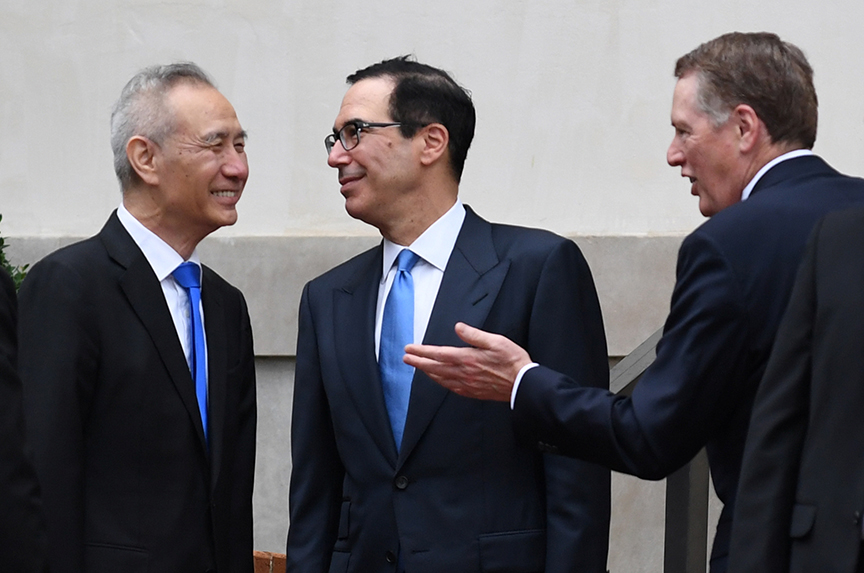

Image: From left: Chinese Vice Premier Liu He smiled as he talked with US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer as he arrived at the office of the Trade Representative for further trade talks in Washington on May 10. (Reuters/Clodagh Kilcoyne)