Arnaud de Borchgrave, UPI Editor at Large, notes that the recent shocks in the U.S. and world financial markets have created a radical realignment in global perceptions

:

Even though the Moscow Stock Exchange was closed twice by Kremlin edict after plunging 50 percent, the Russian leadership could barely contain its glee over U.S. discomfiture. U.S. global economic leadership, gloated Soviet leaders, is now at an end. President Dmitry Medvedev blamed selfish “American capitalism” for the Wall Street meltdown. “Casino capitalism” was a little less disreputable than “bandit capitalism,” but both were widely used at home and abroad.

EU countries echoed Moscow’s call for multilateralism in financial regulation. For French President Nicolas Sarkozy, “laissez-faire” free-market economies would soon go the way of the dodo. Other powerful European voices said the world will never be the same again.

China, confident of its steady ascendancy to superpowerdom, let it be known through think tank exchanges that the moment when Beijing could look Washington “straight in the eye as equals” would come a little sooner than anticipated. Say 2025 instead of 2030.

Thomas Friedman, demonstrating his legendary capacity to spin grand theory out of a single anecdote, sees freespending Swedish tourists as a sign that the United States is losing its sovereignty.

We are all Swedes now. Forget about “Live Free or Die.” Until we get our financial act together, our motto is going to be: “Swedish spoken here — or Arabic or Chinese or German …”

I’m not so sure.

We’ve been hearing that China is going to become the Next Great Superpower for at least a quarter century now and the combined European economic monolith has been poised to overtake the U.S. as the leading economic actor for quite some time. While the relative position of both China and Europe has grown stronger, the United States remains easily the most powerful economic actor and that shows no sign of changing. As with predictions in the 1990s that Japan, Inc. would overtake us, projecting short-term trends into the distant future will likely prove wrong.

Europe is having plenty of economic problems of its own and most are of its own making. While tighter regulation of the financial markets, especially on the Continent, has insulated most EU countries from some of the worst shocks of the crisis, it also inhibited some of the spectacular gains that the United States has experienced over the past several decades. Similarly, while Europe’s economic system has done a better job of protecting the poor — notably, in providing health care, retirement benefits, and other protections — it has come at the price of much less opportunity to become wealthy.

De Borchgrave writes, “Osama bin Laden’s Sept. 11, 2001, attacks inflicted some $700 billion worth of damage to the U.S. economy. The government bailout is worth, again thus far, $700 billion.” That’s a brilliant line; indeed, I awarded it Quote of the Day honors. But the fact that we have the ability to provide $700 billion in loan guarantees in a matter of days — without it even entering into anyone’s mind whether the necessary credit would be extended to the Treasury — demonstrates how massive the American economy is. While I strongly decry the spending recklessness that got us into this mess, the fact of the matter is that the United States has the wherewithal to absorb, in short order, a $700 billion hit from al Qaeda, a $700 billion war, and a $700 billion bailout. To be sure, it’ll hurt. But, frankly, not all that much.

Michael Clemens of the Center for Global Development provides some interesting perspective.

The entire effect of the 1994 so-called “Tequila” Crisis on per-capita real income of the average Mexican . . . was erased in exactly three years. In Thailand, epicenter of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, it took all of six years. In Indonesia, the poverty rate in the population was back to its pre-crisis level within just three years. Even the big, bad 1982 Latin American debt crisis, in this figure, looks a lot more like mean reversion: Yes growth was bad in Mexico after 1982, but it had been unusually high in the years beforehand, and the net result is that real income per capita simply reverted to its historical trend. The same goes for Thailand in 1997. Bad years are typically followed by offsetting good years, and good years by bad. The good years get smaller headlines, or none at all.

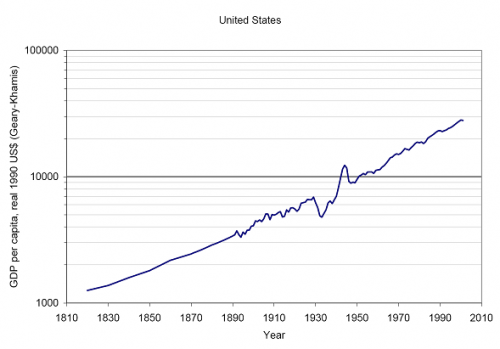

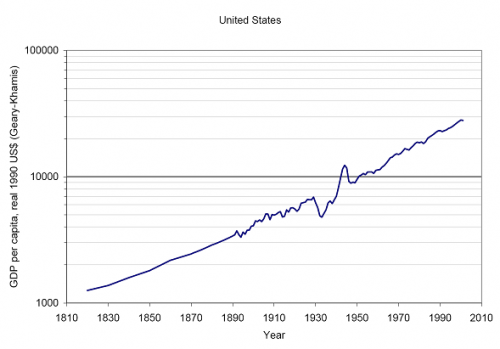

He also points us to this graph of real GDP per capita for the last 200 years of American history:

He writes:

Over these years we had violent financial crashes of various types, bank panics, piles of recessions and a huge depression, many foreign wars and one enormous domestic war, had a central bank and didn’t, were on the gold standard and weren’t, had governments topple in scandal and multiple leaders assassinated, and what did it all amount to in the medium to long run? In per-capita income terms: Nothing. The overall trend does not bend or shift. Every bad year was followed by a good year that returned us to trend. The US average growth rate of real per capita incomes over the last 190 years has been 1.8% a year, and the same rate over the last 10 years has been…. 1.8% a year. Stare at that graph: The Great Depression was traumatic in countless ways, but astonishingly, it’s not clear that we are any worse off today than we would be if the whole thing never occurred. Anyone who made such a claim in the 1930s would have been scoffed at, but that’s what happened.

Obviously, as financial analysts like to remind us, past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is, however, the best indicator we have.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council.