Even as it supports the Olympic thaw between North and South Korea, US President Donald J. Trump’s administration is keeping up pressure on Pyongyang, evidenced by US Vice President Mike Pence’s promise that the “toughest and most aggressive” sanctions on North Korea are imminent.

Even as it supports the Olympic thaw between North and South Korea, US President Donald J. Trump’s administration is keeping up pressure on Pyongyang, evidenced by US Vice President Mike Pence’s promise that the “toughest and most aggressive” sanctions on North Korea are imminent.

On February 7, two days ahead of the opening ceremonies of the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, Pence described North Korea as having the “most tyrannical and oppressive regime on the planet.” He insisted that the United States will continue to intensify the heat of sanctions until North Korea takes concrete steps toward denuclearization.

By the tone of Pence’s remarks, it would seem that in Washington’s eyes a joint Korean Olympic team does not amount to a “concrete step,” and US officials are right to remain skeptical, according to Alexander Vershbow, a distinguished fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center on Strategy and Security.

“Seoul and Washington should be under no illusion that the North’s charm offensive is anything but an attempt to drive a wedge between the United States and its Korean allies aimed at loosening the noose of economic sanctions,” said Vershbow, a former US ambassador to South Korea.

The Trump administration’s plan to enhance sanctions seems to show that Washington is not fooled by Pyongyang’s recent restraint.

While Pence had left open the possibility of meeting North Korean officials while in South Korea, North Korean officials announced on February 8 that there will be no meeting with Pence or other members of the US delegation.

While the threat of more sanctions may seem at odds with Pence’s scheduled appearance at the Games alongside North Korean officials, the move is part of a broader strategy to finally bring Kim to the table to discuss slowing his march toward a nuclear North Korea.

“Looking beyond the Games,” Vershbow said, “the United States should keep the North Koreans on the defensive not through more saber rattling, but by opening the door to dialogue on a durable de-escalation of tensions leading to the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.”

The 2018 Winter Olympics have served as a forum for sports diplomacy on the divided peninsula, thawing tensions between historical rivals.

After talks between North and South Korean officials in the demilitarized zone (DMZ) on the border between their countries earlier this year, it was decided North Korea would join the Games. The decision received a positive response from an international community looking to improve ties with Kim’s regime.

“By acceding to North Korea’s desire to join the Republic of Korea (ROK)-hosted Winter Olympics, the government of [South Korean President] Moon Jae-in has enabled a relaxation of tensions—however temporary—and a modest North-South dialogue,” said Robert A. Manning, a senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center on Strategy and Security. He added: “Few expect it to lead to significant North-South reconciliation or progress toward denuclearizing North Korea, but it does open the door to new opportunities just a crack.”

North and South Korea athletes will march under one flag and compete as a unified team throughout the Games, a decision which has been met with a degree of resistance. While this decision is not enough for Washington to say North Korea is on the right track to de-escalation or relax sanctions on the Kim regime, according to Vershbow, it may help the Games run a little more smoothly.

“The United States was smart to welcome the ‘thaw’ in relations between North and South Korea in the lead-up to the Olympics, ensuring that the Games can take place without violence,” he said.

Manning added: “Given the risks of North Korea’s provocative pattern of behavior, it can be viewed as a low-cost insurance policy for a successful Olympics.”

On the other hand, “that Kim Jong-un decided to hold a military parade [ahead of the Games] does not inspire confidence,” he said. North Korea held a massive military parade on February 8 to mark the founding of the Korean People’s Army by Kim’s grandfather, Kim Il-sung.

While positive steps have been taken, symbolic overtures will not be enough to heal the rift between the two Koreas. “Public opinion in the ROK is divided, reflected in a tumbling of Moon’s approval rating,” said Manning. He added: “Some see Seoul as being too accommodating, and the decision to field a joint women’s hockey team—at the expense of South Korean athletes—is one point of contention.”

Skeptical about whether the cooperation surrounding the Olympics will lead to lasting change from Pyongyang, Manning said: “It will be surprising if the quasi-détente survives beyond March.”

The United States and South Korea plan to conduct military exercises in April, “and Kim will likely continue his aggressive nuclear and missile testing,” he predicted.

Rachel Ansley is assistant director of editorial content at the Atlantic Council.

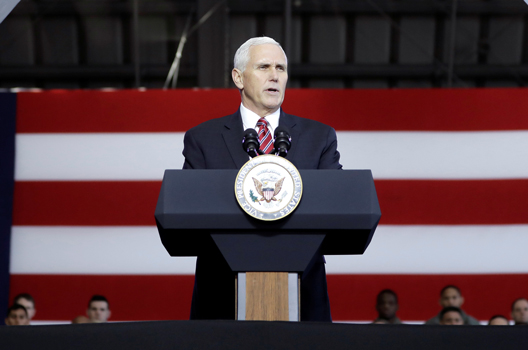

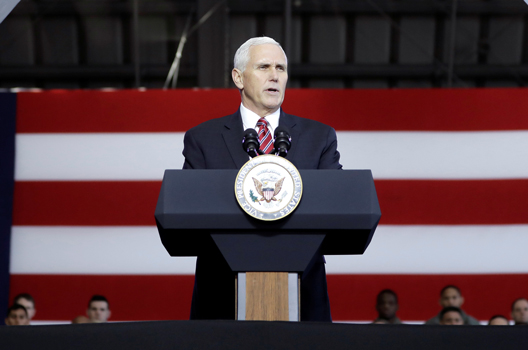

Image: US Vice President Mike Pence addresses members of U.S. military services and Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) before he departs for South Korea, at U.S. Air Force Yokota base in Fussa, on the outskirts of Tokyo, Japan February 8, 2018. (REUTERS/Kiyoshi Ota/Pool)