The European Union has reached its mid-twenties.

On its twenty-fifth birthday on November 1, however, there were no fireworks, inspiring speeches, or fancy receptions in Brussels though. Mired in internal quarrels, from Brexit to rising Euroscepticism, European leaders may feel there is not much to celebrate.

Even the robust economic expansion of recent years is slowly and surely coming to an end, as the recently released EU fall forecast points out. The predicted anemic growth of 1.7 percent in 2020—the lowest since 2014—comes after weaker data than expected during the third quarter of 2018.

Yet, for all the circumspection, the achievements of the Maastricht Treaty, which came into effect on November 1, 1993, are massive: from integrating Eastern Europe to creating the euro and advancing political integration.

Integration of Eastern Europe

Sensing the historic window presented by the end of the Cold War, the then twelve-member European Community leaped at the opportunity to shepherd newly independent eastern countries into prosperous democracies. The Maastricht Treaty paved the way for EU eastern enlargement, offering prospective members access to a large internal market, generous regional funds, and increased trade.

In exchange, the EU required these countries to meet the “Copenhagen criteria,” a set of rigorous institutional, economic, and social standards.

Critics claimed the enlargement was rushed, fearing the incorporation of under-ripe candidates and governance complications of a larger, heterodox union. In recent years these concerns have re-emerged as Poland and Hungary face questions over institutional deterioration of the rule of law. But the overall picture shows those fears were unfounded. In the long run, democratic practices have consolidated and economic outcomes have been striking. In a short period of time, Poland’s GDP per capita has risen from 40 percent of the EU average in the early 1990s to 70 percent today, according to Eurostat. By anchoring eastern countries within the EU, the Maastricht Treaty has already had a huge success that is hard to overstate.

An ambitious EU

Simultaneously, the Maastricht Treaty also drove a profound transformation of European institutions. After a single market, endowed with free circulation of goods, services, capital, and people, had been enshrined in the Single European Act of 1987, Maastricht propelled the expansion of the EU into the areas of foreign and security policy, and justice and home affairs cooperation. This expanded ambition is well reflected in the name change, from European Community to European Union.

Even if advances in these areas were embryonic, they were decided via a top-down approach and should have had broader democratic involvement. In any case, it was a move in the right direction: existing deep economic integration eventually needed closer political union to appear legitimate in the eyes of its citizens. In this sense, Maastricht paved the way forward.

Economic governance

Above all, the most visible achievement of the Maastricht Treaty is the creation of a common European currency, the euro.

The euro was meant to achieve price stability, fiscal soundness, economic convergence, and growth. Despite its faults and against the unprecedented financial crisis of 2008, the euro has had reasonable success.

Oversized attention to economically weaker member states has overshadowed the fact that the Eurozone as a single entity is on solid economic footing. The Eurozone today enjoys gross domestic product (GDP) growth, falling unemployment, price stability, and falling public debt (currently at 84 percent of GDP).

This has been possible thanks to the deepening of the Economic and Monetary Union that originated in Maastricht.

To enforce price stability, monetary policy was transferred to an independent body, the European Central Bank, formally established in 1998. Measured by the metric of relative price stability, the bank has been an outstanding success, given the large inflation moves of previous decades. However, the treaty did not ensure sufficient fiscal and financial integration and supervision, which proved a costly mistake during the European debt crisis. Today the ECB has increased financial oversight capabilities and a banking union is slowly being constructed.

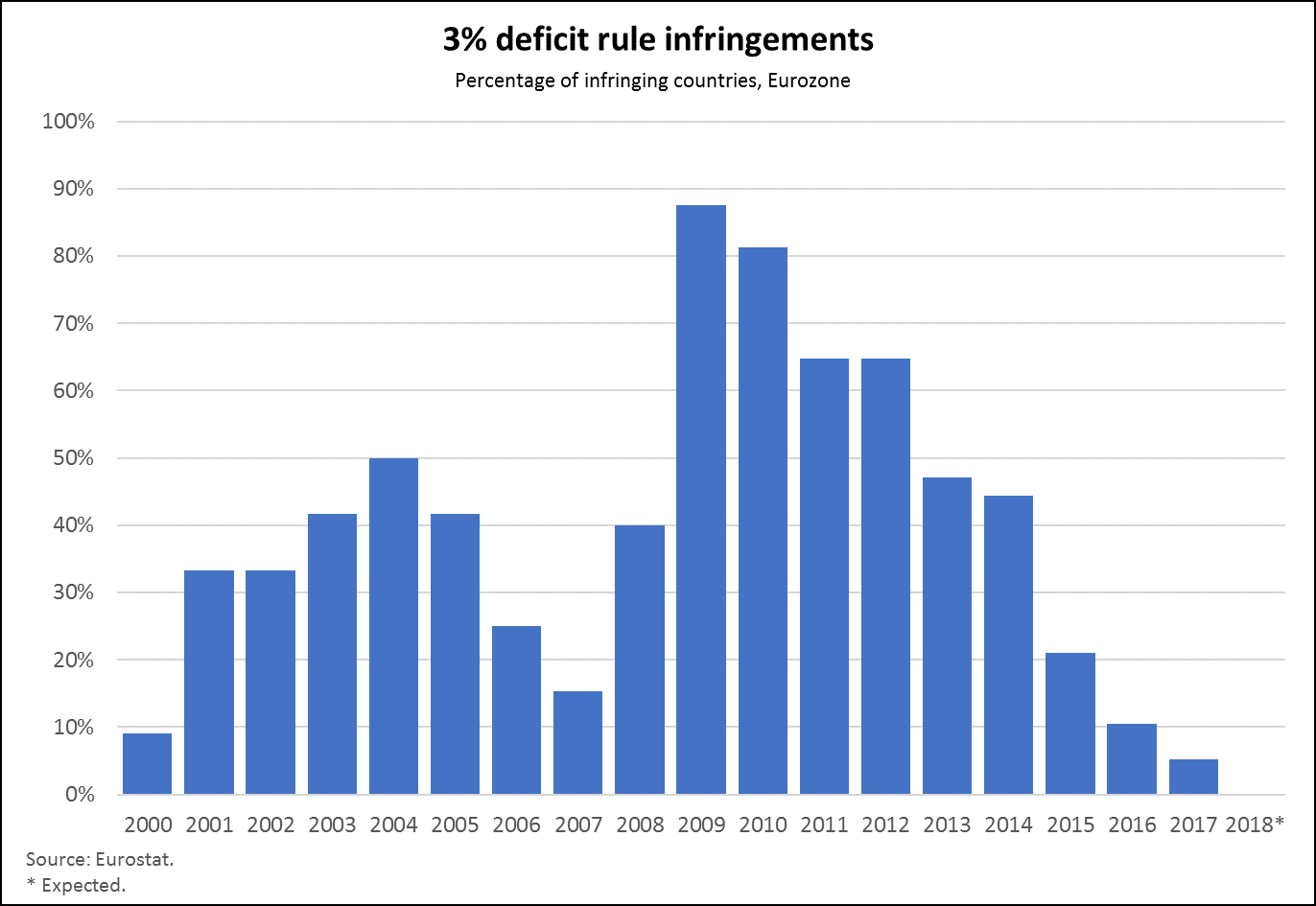

With the goal of ensuring long-term fiscal sustainability, the Maastricht criteria forced member states to keep annual budget deficits below 3 percent of GDP and public debt below 60 percent of GDP. In this area however, the record is less than stellar.

As many critics have suggested, the Maastricht rules may have contributed to pro-cyclical fiscal policies: making things worse during times of crisis and deepening imbalances during expansions. They are also highly complex, hardly transparent, and error-prone, which has helped eurosceptics frame them as a direct infringement of national sovereignty.

What’s more, member states usually get away with not abiding by them, since enforcement mechanisms such as sanctions are hard to impose and can be counterproductive.

Since the Maastricht rules were introduced, there hasn’t been a single year when all EU member states have met its criteria. In fact, 2018 might be the first time ever when all Eurozone (but not EU) countries comply, if Spain is able to meet its target just below 3 percent (see figure below).

European leaders are aware that Maastricht rules need to change. In fact, several reforms have been introduced, notably the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) in 1997, and the so-called six-pack and two-pack measures of 2011 and 2013, respectively. However, the fundamental flaws remain unchecked.

Ambitious reforms proposed by French President Emmanuel Macron would seek greater fiscal integration to stabilize the economy in the face of sudden shocks that cannot be managed at the national level alone. In the current political climate, however, these efforts have so far faltered.

Eventually, the Maastricht fiscal framework will need to evolve. History shows that EU integration advances in leaps, rather than a steady climb. Maastricht was a great stride, but for now, the EU will have to content itself with minor tweaks before the next big jump.

Álvaro Morales Salto-Weis is a program assistant with the Global Business & Economics at the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @alvarosaltoweis.

Image: European Union flags flutter outside the EU Commission headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, March 8, 2018. (REUTERS/Yves Herman/File Photo)