We can joke that the United States and Great Britain are two nations divided by a common language. But the gap between the United States and Pakistan is neither humorous nor easily reconciled.

Only a fundamental improvement in mutual understanding can rectify the enormous misunderstandings and misperceptions on both sides that threaten this crucial relationship and the countries’ mutual security.

Despite two U.S. presidents declaring Pakistan a major non-NATO ally and promising to implement a new strategic relationship, from Islamabad’s view, the flowery prose hasn’t been accompanied by deed.

And, seen from Washington, Pakistan is often a truculent, uncooperative and difficult partner.

Pakistanis believe that American presidents have virtually unlimited power and authority to make things happen and are angry over what is seen as non-delivery of promises.

Americans don’t appreciate that the Pakistan People’s Party is in a coalition government needing 42 additional seats to hold a majority in a National Assembly of 342 members.

Unfortunately, the White House has reversed the pitfalls of a coalition government (as in Britain or Iraq) with a perception of an absence of political leadership in Islamabad. Perhaps the loss of both houses of the U.S. Congress in November will change its mind.

Pakistanis ask what their country has gotten out of its relationship with America. The United States’ war on terror has cost them dearly: more than 31,000 civilian and military casualties; a spreading insurgency; and a hemorrhaging economy even before super floods ravaged the nation.

The Kerry-Lugar-Berman Act approved $1.5 billion a year in support for five years but only about 10 percent has been transferred and most Pakistanis believe no money has arrived. Since Sept. 11, 2001, the United States has underwritten the Pakistani army to the tune of about $1 billion a year. Unfortunately, that funding has been sent in drips and drabs.

Further, from Islamabad’s perspective, the United States has done little to facilitate better relations between India and Pakistan and the $3.5 billion arms deal signed between New Delhi and Washington didn’t help.

Finally, given its stand on human rights, American silence over India’s martial crack down in Kashmir signals to Pakistanis a double standard.

The conviction and sentencing in a U.S. District Court in New York of Dr. Aafia Siddiqui to 86 years in prison for terrorism and attempted murder have precipitated a huge backlash intensified by NATO’s hot pursuit of Afghan terrorists into Pakistani territory Monday.

These and other incidents underscore profound Pakistani doubts over U.S. reliability and sincerity in defining a new strategic relationship.

Americans have equally powerful points of contention and legitimate grievances with Pakistan. The White House worries that excessive cronyism prevents competent people from serving in Pakistan’s government. Corruption remains a divisive issue.

U.S. leaders don’t see that their strategy in Afghanistan is fully supported, and is perhaps even opposed, by Pakistan. Repeated delays in obtaining visas for U.S. military and government personnel have disintegrated into mini-crises. And Pakistan’s long-standing policy on “fraternization with foreigners” precludes Pakistan army officers meeting socially with foreign contemporaries without permission, further contributes to this trust deficit.

But Pakistan is in or close to extremis precipitated by simultaneous security, economic and now humanitarian crises. Worse, a fourth, politically charged showdown between the chief judge and the government looms. The consequence could be political chaos if the chief judge rules part of the 18th amendment unconstitutional and denies presidential constitutional immunity over allegations of wrongdoing prior to taking office.

Parallels are inexact. Watergate and the impeachment of Bill Clinton over the Affaire Lewinsky crippled the U.S. government. So, too, Pakistan’s government could effectively be shut down or dissolved by a chief judge preoccupied with enhancing his own authority rather than on the destructive consequences for the nation.

Some misunderstandings and grievances may not be resolvable. That doesn’t mean we cannot try. The last chance may be a very serious meeting between the two presidents to work out these differences and begin restrengthening this strategic relationship that is absolutely vital to achieving even a modicum of peace and stability in the region.

After Pearl Harbor and U.S. entry into World War II, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill understood the need for intense, intimate and continuing dialogue. A weekend meeting at Camp David or some other remote location for the leaders of Pakistan and the United States could begin such a process. Careful, advance preparation by both sides, of course, must be assured.

The driving force is the explosive ignition of Pakistan’s security, economic and political crises by the humanitarian catastrophe that Pakistan cannot handle alone. Here, even the possibility of the floods putting Pakistan in extremis is strong enough a rationale to get this vital strategic relationship back on track while closing the trust deficit and mitigating the legitimate differences that deeply divide us. Otherwise, the United States and Pakistan will profoundly suffer.

The only question will be how much.

Harlan Ullman is Senior Advisor at the Atlantic Council, Chairman of the Killowen Group that advises leaders of government and business, and a frequent advisor to NATO. This article was syndicated by UPI. Photo credit: UPI.

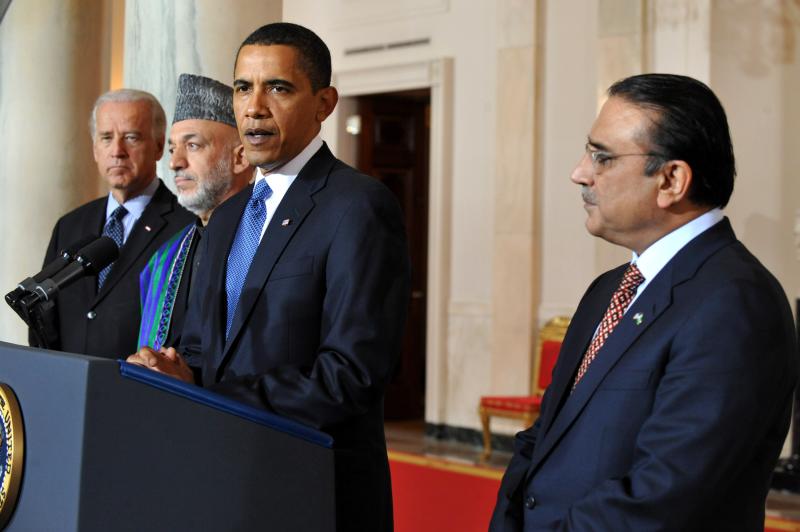

Image: Obama-Zadair-and-Karzai.jpg