The year 2019 saw a wave of demonstrations across Latin America, and governments have attempted to respond to citizen demands with varying degrees of vigor and success. In Panama, citizens have taken to the streets in recent years to protest government corruption. Now amid the COVID-19 pandemic, fresh allegations of corruption and institutional inefficiencies are fueling a renewed push towards reforms and greater transparency. In order for Panama to emerge from the pandemic with inclusive and sustainable growth, the country needs a new social contract that combats corruption and provides equal opportunities for everyone. With the election of Joe Biden—who brings a strong commitment to Latin America and the Caribbean—as president-elect of the United States, now is the perfect time for Panama to take concrete steps to improve its image, in order to attract investment from and strengthen economic ties with the United States.

Corruption has persisted in Panama for decades. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Panama loses $520 million a year—approximately 1 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP)—to corruption. Investigations surrounding the Odebrecht Case, the largest corruption case in Latin America and the Caribbean, concluded in Panama on October 14, 2020: The Brazilian construction company was found guilty of paying more than $100 million in bribes to officials in the governments of former Panamanian presidents Martín Torrijos (2004-2009), Ricardo Martinelli (2009-2014) and Juan Carlos Varela (2014-2019). But only ten out of the one hundred individuals charged have been convicted with crimes. The fate of the rest of the suspects lies at the hands of Panama’s judicial system, which is often criticized for being neither independent nor depoliticized.

As of last month, the Attorney General’s office was investigating over a dozen crimes against the public administration related to irregularities in contracts, cost overruns, and the use of state bonds during the pandemic. Among the several government officials under investigation, Vice President and Minister of the Presidency José Gabriel “Gaby” Carrizo was accused of overpricing medical equipment and awarding multimillion-dollar contracts to advertising firms. Minister of Public Works Rafael Sabonge has also been targeted by social media campaigns demanding his resignation after allegedly purchasing hospital infrastructure at inflated prices. Earlier in May, Public Security Minister Juan Manuel Pino sought to buy $7.1 million worth of weapons and ammunition, putting the purchase on hold only after public pressure. And while the country’s Social Security Fund (Caja de Seguro Social, or CSS) struggled to find ventilators for COVID-19 patients, Vice Minister of the Presidency Juan Carlos Muñoz issued letters of commitment to acquire ventilators at $49,000 each, far above the market price of $5,000 each. Amid protests, Muñoz resigned.

Between September 2019 and September 2020, Panama increased its public debt by $7.5 billion, bringing the total to $36 billion. For the first time since 2006, Panama’s public debt has risen above 50 percent of the country’s national GDP, amid allegations of fiscal mismanagement by the government. As a result of a deterioration in Panama’s fiscal and debt metrics, Moody’s revised the country’s outlook from stable to negative. Government-issued bonds have largely contributed to this increase in Panama’s public debt, with limited clarity or transparency regarding how these funds will be allocated.

A series of other factors, when combined with criticisms over corruption and the country’s rising debt, could unleash social unrest in Panama in the coming months. With a projected GDP drop of 13.6 percent this year, unemployment will grow from 7.1 percent to 25 percent. In other words, the number of people without formal employment will more than triple, with the most affected demographic being those under the age of thirty.

In times of crisis, confidence and credibility in institutions is needed more than ever. Plagued by international scandals in recent years, and after being added to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) gray list, the Panamanian government needs to help improve the country’s image to bolster foreign investment. US President-elect Joe Biden will bring a return to US leadership in the region via the mobilization of private investment and the prioritization of economic development. Panama must be able to provide confidence in the equitable and transparent use of resources to generate profitability to investors and the Biden-Harris administration. Attracting foreign investment can help boost sustainable and inclusive economic growth, as well as productivity and the labor force, all of which will be crucial to the post-pandemic recovery.

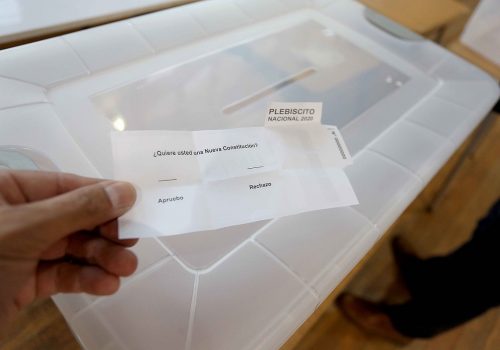

While the COVID-19 pandemic presents a number of new socioeconomic challenges and intensifies weaknesses pertaining to inequality and corruption, it also presents an opportunity for the Panamanian government to rethink the future. Panama can emerge from this crisis and embark on a dynamic and sustainable growth path, but only if the country devises a new social contract that strives to provide equal opportunities for all. As in the case of Chile, which on October 25 voted to rewrite the country’s Constitution after mass protests against inequality, a new social contract for Panama must be designed together with its society and must include key proposals for revitalizing the economy, which was one of the fastest growing in the world prior to the pandemic. Most critically, the creation of institutional incentives to deter corruption and an independent judicial system that prosecutes, convicts, and sentences individuals found guilty of corruption must be put in place to address improbity.

These recommendations are further detailed below:

- Citizen engagement: The United Nations (UN) argues that involving citizens in governance structures, such as an anti-corruption authority, is an important way to prevent corruption. In addition to nonviolent protests, citizens can pressure governments to be transparent and accountable with awareness-building social media campaigns and websites that track government irregularities and register corruption complaints. Among several civil society initiatives, independent digital journalism company Nueva Nación collects, analyzes, and disseminates public data to promote transparency and encourage civil debate in Panama.

- Economic revitalization: Set to experience a double-digit economic contraction and unprecedented public indebtedness, the government must boost the economy, while also being transparent and prudent in using its resources. At the same time, the pandemic has exposed vulnerabilities in Panama’s health, social, and education systems that must be addressed in order for the recovery to be truly inclusive and sustainable. One example that Panama could follow is what Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean Executive Secretary Alicia Bárcena outlines as a digital basket—a proposal that would provide a cell phone, a laptop or tablet, and broadband access—to support connectivity for low-income households across the region; in Panama, less than 40 percent of students have internet access. Panamanian President Laurentino Cortizo announced a $30 million Solidarity Education Plan (in Spanish, Plan Educativo Solidario) to allow free internet access to public school students, but so far there are only 8,300 active students using the free platform.

- Institutional incentives: Panama must consider following the actions prescribed in The World Bank’s recently-launched set of Anticorruption Initiatives that aim to combat corruption. The suggested actions intend to help countries follow global standards and monitor activity; understand elite networks of corruption; develop sector-based approaches to combating corruption; promote transparency and access to information; and address facilitators of corruption. Based on Panama’s vigorous anti-corruption movement, the government could take concrete steps to promote transparency and access to information by designing data driven policies and working with civil society to promote and deliver trainings on such policies for anti-corruption and accountability.

- Independent judicial system: Corruption in Panama’s judicial system, and especially among its judges, has been reported for years, undermining the country’s democracy. Panama could consider signing an agreement with the UN for the creation of an independent commission—similar to Guatemala’s International Commission against Impunity (CICIG), which gained international acclaim before Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales terminated the agreement after CICIG investigated him—to support state institutions specifically in the investigation of crimes committed by the judicial branch. Lessons learned from CICIG’s rise and fall in Guatemala will be critical in Panama to ensure rule of law prevails over the interests of the elite. The establishment of an independent commission in Panama would also help strengthen economic ties with the next US administration, with President-elect Joe Biden being a strong supporter of Guatemala’s CICIG and corruption being among his key concerns for the region.

Cristina Guevara is a program assistant for the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

Further reading:

Image: Protester are seen with bands on their heads during an anti-corruption march in Panama City July 1, 2015. The band reads "No to Corruption in my Panama". REUTERS/Carlos Jasso