After a year of instability, Chileans vote in a critical referendum on October 25 that will determine whether a new, democratically enacted constitution will replace the one originally imposed by dictator Augusto Pinochet in 1980. While the new constitution could help jumpstart efforts to alleviate many of the inequalities in Chilean society, the struggle to get to this point should give caution to other countries that have left structural inequalities unaddressed.

Not so long ago, Chile was considered the most prosperous country in Latin America. With a per capita gross domestic product close to fifteen thousand dollars, credible macroeconomic policies, institutional stability, and an expanding middle-class, Chile was viewed as an economic success story following its return to democracy in 1990.

That perception faltered in October 2019. What began as a student-led protest in Santiago against a 4 percent hike in metro fares soon became massive, countrywide demonstrations. Following looting, arson, and vandalism of public and private property, Chilean President Sebastian Piñera imposed a state of emergency that included curfews and military deployments in the streets. Complaints of human rights violations accumulated as citizens and international organizations claimed excessive use of force by law enforcement agents.

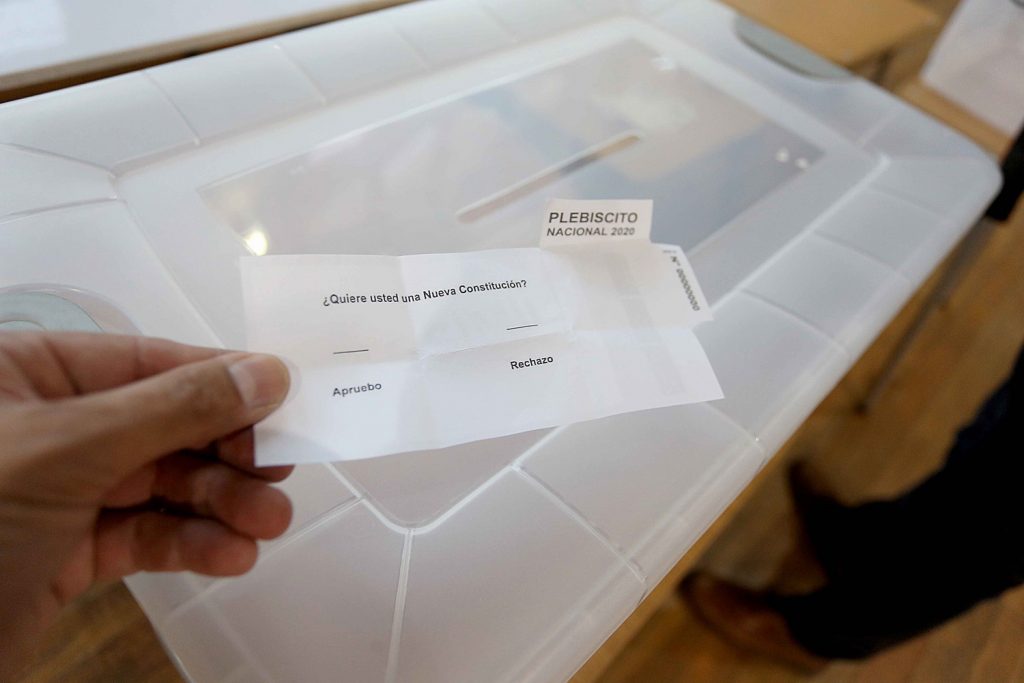

As protests grew, Piñera committed to social welfare reforms, changed one third of his cabinet, and reached an agreement with the opposition to hold a referendum in April 2020 to replace the constitution. Because of the COVID-19 crisis, the referendum was postponed—it will finally take place this week. However, the government’s approval rating remains low, and as the country reopens, tension is increasing on the eve of the referendum.

The protests in Chile raised concerns with the structural weaknesses of what has been called “el modelo” (the model): a set of free-market fundamentalism rules enshrined in Pinochet’s constitution that over the years failed to bridge Chile’s inequality gap in a meaningful way. Today, a majority of Chileans remain vulnerable to economic shocks and lack access to quality public services.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made the socioeconomic divide more striking than ever before. In May 2020, former Chilean Health Minister Jaime Mañalich recognized, amid the rapid spread of the virus, that “there is a level of poverty and overcrowding that I was not aware of.” This happened a few months after Piñera said that Chile was a “true oasis” in a troubled region.

“Despite the economic improvements of the last decades, many feel they were left behind. The explosive upheaval that we witnessed was the uprising of the excluded,” said Harley Shaiken, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley that specializes in Latin America and believes the new constitution could be an opportunity to create shared prosperity.

What is going on in Chile should pique the interest of other Latin American countries and the United States. The South American country of nineteen million people could be a canary in the coal mine: an advanced warning to wealthy countries that have lingering inequality issues. What is happening in Chile could happen elsewhere. The Chileans in the streets are decrying a ruling class they see as disconnected from the concerns of average citizens. They also have diffuse demands: more balanced distribution of income, less influence of the private sector on politics, improved health services, better quality of education, rights for minority groups, a reduction in the costs of living, an expanded social safety net, and a replacement of the country’s dictatorship-era charter. The movement is leaderless and not affiliated with a political party—it is a populist outpouring.

When governments are not able to fulfill the expectations for increased living standards, the idea that liberal democracy is the best way to address society’s demands runs the risk of starting to fade. That is why this upcoming vote is so important. People on the streets must realize they do have a voice; this avoids further fractures in society.

To achieve reconciliation, Chile needs a national project; that is, a concerted roadmap to achieve prosperity that includes a clear pathway to improve everyone’s wellbeing and reduce inequality. As Oscar Landerretche, former board chairman of the Chilean state-owned copper company Codelco and professor at the University of Chile, said: “All countries, rich and poor, need a national project to unite society. People also need to know how they contribute to that project, and what the rewards for their sacrifices are going to be.” This is precisely what a new constitution could provide.

It is not difficult to imagine that what happened in Chile could come to happen in other Latin American countries that are struggling to close inequality gaps and reduce poverty as polarization and political, economic, and security tensions intensify, all in unique yet familiar ways.

Other countries would be wise to heed the lessons being learned in Chile. Unless structural inequalities are combatted, what looks like broad economic success one day could quickly turn into crisis.

Daniel Payares-Montoya is an intern at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin American Center, and a research fellow at the University of California’s Center for Latin American Studies at Berkeley.

Further reading:

Image: Santiago de Chile, Chile.- In the photo taken on October 22, 2020, a ballot is shown for the plebiscite on Sunday, October 25.