Throughout 2016, Brazilians and foreigners alike kept stating—and hoping—that 2017 would bring more stability, allowing Brazil to reform and grow its economy. But those of us who thought we were heading into calmer waters will have to think again.

Throughout 2016, Brazilians and foreigners alike kept stating—and hoping—that 2017 would bring more stability, allowing Brazil to reform and grow its economy. But those of us who thought we were heading into calmer waters will have to think again.

The new year is gearing up to be another tumultuous one for Brazil, in spite of the country’s recent political recalibration.

The past several weeks have shown that political stability is still out of reach. Just look at the attempted removal of the Senate president, Renan Calheiros, by a Supreme Court justice in early December. Calheiros, an ally of Brazilian President Michel Temer, managed to stay in power, but mounting accusations against him for suspected involvement in the Car Wash corruption scandal have raised questions about his political survival.

This brief crisis in the Senate revealed that Temer, who took over the reins of power after former President Dilma Rousseff was impeached in August, has to depend on the support of a shaky National Congress. It also provokes doubt about the administration’s ability to pass important proposals quickly and without mishaps: the vote for one of the most important measures to rebalance the economy—the cap on public expenditure for twenty years—was nearly postponed to 2017 in the middle of the Calheiros debacle. Had it been postponed, pessimism about the economy would have skyrocketed.

But the greatest threat to political stability right now is the expected, plea-bargained testimony from imprisoned executives of Odebrecht, the construction giant that has been at the center of the Car Wash storm. Their testimonies are bringing the scandal ever closer to Temer and his inner circle. It is rumored that the executives will accuse eleven cabinet ministers and around one hundred congressmen of corruption, many of whom are important allies of the administration.

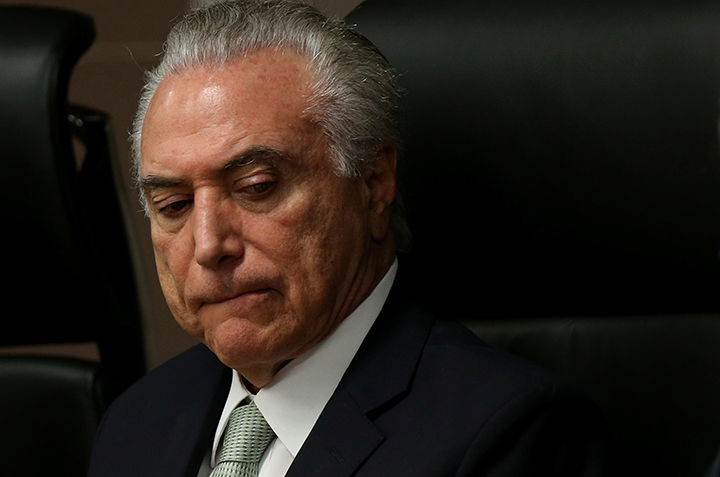

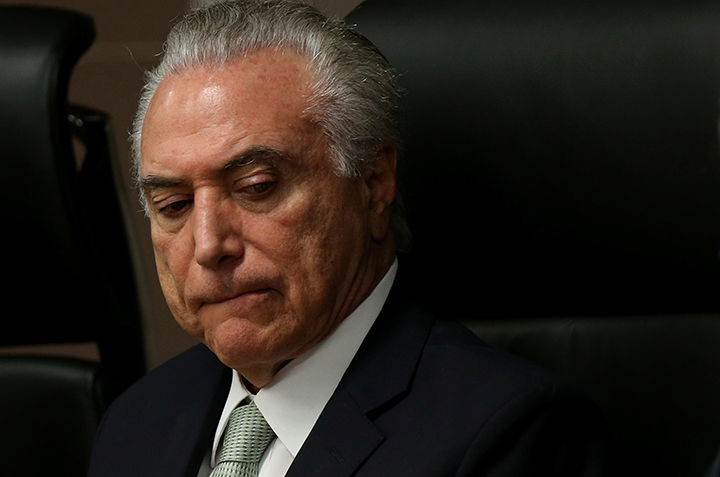

In the midst of these dark clouds, Temer’s popularity has sunk to levels close to those of Rousseff’s before her impeachment. The president might also face trial in the Superior Electoral Court for allegedly using irregular donations to run his campaign in tandem with Rousseff three years ago. Temer’s political degradation, together with his low approval ratings and the general pessimism about the economy, could put pressure on the court to invalidate the president’s mandate from the 2014 election. Ousting Temer in 2017 would prompt an indirect election of a new president by the Brazilian Congress. A general election would not be held until late 2018. Such a dramatic turn of events would benefit nobody.

Leadership elections in both houses of the National Congress will be held in February. The Senate race seems to point toward a victory for Sen. Eunício Oliveira, Calheiros’ right-hand man. Elections in the Chamber of Deputies, in turn, will test Temer’s ability to maintain his cohesive base, as at least four strong allies of the administration are vying for the position.

Even if some of these candidates drop out of the race, the government’s fragmented legislative base reveals the difficulties Temer will face. To avoid an even greater split amongst his allies, the president may have to offer dissatisfied members ministerial positions. Accommodating all factions will not be easy. If Temer is unable to stabilize his base, he will face congressional turbulence in 2017. This instability would undoubtedly impact the much-anticipated pension reform, a key part of Temer’s agenda.

Big waves on the economic front will come just as the new year begins. On January 11, the Monetary Policy Committee (Copom) of the Central Bank will decide on a new interest rate. The Copom is likely to accelerate interest rate reductions. There is a good chance these cuts will continue throughout the year, provided inflation remains under control.

In February, Temer’s economic team is expected to announce the first annual budget under the new expenditures limits. Faced with market pessimism, it is also likely that it will announce economic stimulus measures, including possibly measures to increase available bank lending.

Although the domestic situation will be the deciding factor for economic growth, external elements will also impact the Brazilian economy in 2017. Donald Trump’s inauguration as the next president of the United States in January and the uncertainty that surrounds the new US administration may cause an outflow of investments from Brazil and other emerging economies. The expected, continued hikes in US interest rates will also impact the Brazilian market. Higher US interest rates, combined with low Brazilian interest rates and continued political instability, will increase even more the possibility of negative capital flows.

The congressional calendar of additional reforms, and monetary and fiscal policies suggest that 2017 will be as hectic, if not more so, than 2016.

Ricardo Sennes is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

Image: Brazilian President Michel Temer’s popularity has plummeted since he assumed the presidency after the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff in August. (Reuters/Adriano Machado)