British Prime Minister unlikely to get his way on curbing welfare payments to EU migrants, says Atlantic Council’s Fran Burwell

British Prime Minister David Cameron will likely get some of his demands for reform of the European Union, but on at least one — curbing welfare payments for EU citizens migrating to the United Kingdom — he is likely to face considerable pushback, said Fran Burwell, Vice President for European Union and Special Initiatives at the Atlantic Council.

Cameron, in a letter to European Council President Donald Tusk on Nov. 10, presented four goals for reforming the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union. He wants to increase economic competitiveness within the EU, a larger role for national parliaments, safeguards for countries that do not use the euro, and to slow migration by other EU citizens to the United Kingdom by curbing welfare payments for four years.

“Things like competitiveness is the direction Europe wants to go in any way,” said Burwell.

But Cameron will find it more difficult to get his way on removing the words “ever closer union” from European treaties and barring immigrants from other EU countries from social welfare benefits for four years, she said.

“The obstacle he is more likely to face is the charge at home that he has not been ambitious enough. There are those in Britain who want a total remake of the relationship, and I don’t think he comes close to that,” she added.

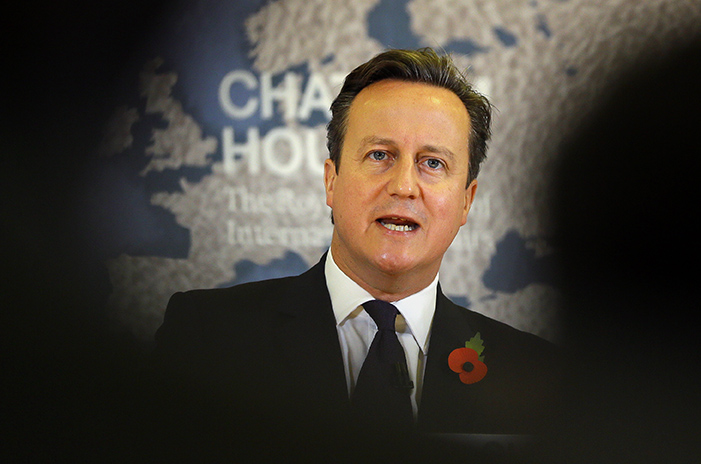

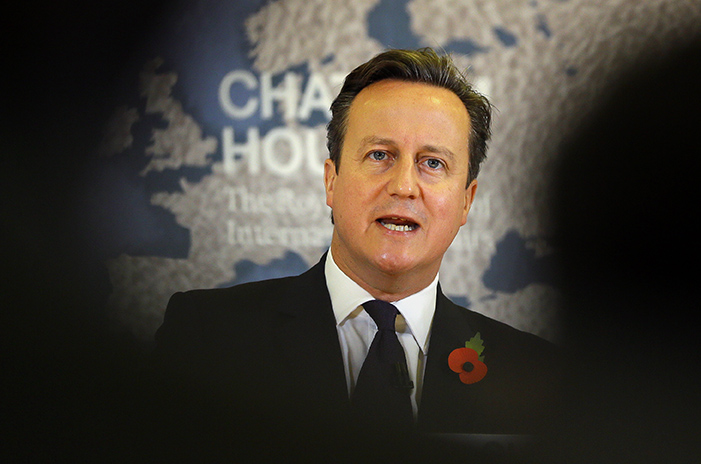

Cameron has promised to hold an in/out referendum before the end of 2017 on whether the United Kingdom should remain in the EU. Speaking at Chatham House in London on Nov. 10, he said the United Kingdom faces a “huge decision” in the referendum.

Cameron’s demands will be discussed at the EU summit in Brussels in December.

Fran Burwell spoke in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts from the interview:

Q: Why does Prime Minister Cameron want to change the United Kingdom’s relationship with the EU?

Burwell: In some ways this is a domestic British issue. Within Britain there has been, since the beginning of its relationship with the then European Community, a lot of ambiguity over whether Britain was committed in the same way as the continental European states.

Winston Churchill was very much in favor of a United States of Europe, but not with Britain inside. It took a couple tries for Britain to get in, but it has always been a little bit different for them than it has been for the others. That is largely historical. The others —the French, the Germans, the Italians — were devastated by World War II. For them joining what eventually became the EU was a way of ensuring that war would not break out again. For the British, joining coincided with the final loss of empire and so reaching out to the continent marked a diminution of its status.

While it is partly about this long-running domestic debate, it is also partly that the EU can be a very cumbersome governing organization and much more fond of regulations than many of the British. The EU has become a place where Britain can be outvoted. The EU is about pooling sovereignty. That is not what a lot of the British are eager to do.

On the other hand, the EU is Britain’s major trading partner. And, for example, it would be much more difficult for all the Britons who have retired to Spain if they were no longer members of the EU.

Yet there are many in Britain who believe that Britain by itself is the best way to control its future destiny.

Q: Are the Prime Minister’s goals a) significant or b) modest? Of the four goals, which will be the most difficult to get done?

Burwell: Some of them are significant and some are not.

One of the goals is competitiveness. Most of those in power in the EU right now want greater competitiveness. It is actually striking how much the current European Commission under Jean-Claude Juncker talks a British talk in terms of competitiveness: capital markets union, digital single market, completing the single market. Completing the single market is one of the things the Prime Minister has argued for in his letter and he will not find opposition in Brussels to that aim. It’s just that when it comes down to actually doing it, sometimes it is very difficult. You are trying to remove the obstacles between twenty-eight different systems.

Competitiveness is the direction Europe wants to go in any way. Other demands, such as removing “ever closer union,” which has been a key phrase in the treaties, will be much more difficult. Also, the idea of having immigrants from other EU countries not be eligible for social welfare benefits for four years will meet some opposition. The ideal is that no EU citizen should be discriminated against compared to what a British citizen would receive.

Let’s assume the Prime Minister will not get everything he has asked for, but he will get some of it. The obstacle he is more likely to face is the charge at home that he has not been ambitious enough. There are those in Britain who want a total remake of the relationship, and I don’t think he comes close to that.

Q: Do Britain’s demands open up the door for similar proposals from other EU members?

Burwell: There certainly is a concern that the way these demands have been posed makes it more divisive. Many in the EU agree with the Prime Minister’s criticisms of the European Union. They recognize, for example, the need to find a balance between those countries that are in the Eurozone and those that are not in the Eurozone, so that those that are not in the Eurozone and will never go into the Eurozone will not be penalized.

Since much of this debate has taken place in the context of Britain wants an opt out, rather than working with the EU so that the EU as a whole addresses these issues, it has created some resentment. The questions that the Prime Minister has been asking are important ones for the Union, but they need to be discussed, not as a way of getting an opt out for the British, but as a way of improving the Union.

Q: Cameron has pledged to hold an in-out referendum before the end of 2017. If Britain were to leave the EU, what impact would it have on European integration?

Burwell: It would lead to a speed up of integration within the Eurozone. I am struck by how there is a real desire to keep Britain in. Nobody wants them to leave in part for reasons of balance between the big member states. Many other states like the fact that Britain is always there talking about less regulation and better regulation.

Without Britain there will be a much more serious discussion of the Union’s future. It means that the major country permanently outside the Eurozone is no longer there. All the Central European countries pledged that at some point they would enter the euro. It is not going to happen tomorrow. The new Polish government is very much opposed to it. But they are all considered in EU jargon “pre-ins.” It is the Swedish and the Danes, as well as the British, who have opt outs. If you take the British out of that equation you actually put a lot more weight in the Eurozone.

Q: Has the migrant crisis, fuelled by the war in Syria, had an impact on how Britons feel about remaining in the EU?

Burwell: The migration crisis has had an impact. You have the pictures and videos of people at Calais trying to get on trucks and trains. It has been exaggerated in Britain, but there is no doubt that it has had an impact.

It has also had an impact in the other countries in the EU. The others, who are being inundated, do not see the British contribution as equitable burden sharing.

Q: What impact would Britain’s exit from the EU have on its “special relationship” with the United States?

Burwell: It would lead to a significant deterioration in the special relationship. One of the big assets of Britain, as far as the United States is considered, is that they have a similar view on many of the regulatory issues that we have. As we deal with the EU as a regulatory superpower, Britain is more often closer to us than some of the other countries.

We also look to Britain to help marshal our allies, not just in the NATO context. In the EU context when we go, for example, to try and get sanctions on Russia in the wake of the aggression in Ukraine, or to keep sanctions on Iran, we look to the British to help us convince its European partners. That requires a great deal of credibility from the British. Their engagement in Europe has not been as active in the last couple of years while they have been having this domestic debate. So, when we went for the Ukrainian sanctions it was almost entirely through Germany. We would like to have an active, engaged Britain in the EU who could be our partner in working with the EU, but outside they do not have that credibility or that access.

Q: Do you expect Britain to play a greater role in the EU if British voters decide in the referendum to remain part of the Union?

Burwell: I would hope so, but I am not convinced. If they win the referendum to stay in it would probably be by a fairly narrow margin. If they lose the referendum and Britain were to go out, it would reawaken the Scottish question. One thing that emerged from the Scottish referendum last year was the idea that the Scots really didn’t want to leave the EU. It will also raise severe questions for Ireland and the relationship with Northern Ireland.

Ashish Kumar Sen is a staff writer at the Atlantic Council.

Image: British Prime Minister David Cameron delivers a speech on EU reform at Chatham House in London on Nov. 10. Cameron said he hoped to make good progress with the reforms when EU leaders meet in Brussels in December. (Reuters/Kirsty Wigglesworth)