Atlantic Council experts share their take on the outcome of the German elections. Here’s what they have to say:

Atlantic Council experts share their take on the outcome of the German elections. Here’s what they have to say:

Evelyn Farkas, nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Future Europe Initiative, Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center, and Brent Scowcroft Center on International Security. She served from 2012 to 2015 as deputy assistant secretary of defense for Russia/Ukraine/Eurasia, responsible for policy toward Russia, the Black Sea, Balkans, and Caucasus regions and conventional arms control.

On Chancellor Merkel’s re-election

The outcome of this election, which gives the chancellor another mandate, is a positive development for Germany, the transatlantic relationship, and America. The chancellor is a strong leader who understands what is at stake for Europe, especially when it comes to the threat posed by [Russian President Vladimir] Putin and Putinism.

I believe that Chancellor Merkel has the determination, the political will, and the ability to strengthen Europe’s defenses against the Kremlin. This is the number one priority.

The second priority is not merely to respond to the Kremlin per se, but to address the challenge posed by autocracy towards democracy in Europe and elsewhere. She can be the standard-bearer for Western democracy in Europe.

On the US-German relationship

With regard to the US-German relationship, it is positive that she has been re-elected. She already has a relationship with President Trump, and knows what is at stake. There is no need to get her up to speed in any way, shape or form, so she can be effective from day one. She has done a good job advocating for the relationship on terms that our president and this administration understands, by, for example, highlighting the thousands of jobs that Germany and German companies have created in America.

On the AfD’s performance

Globally, we are seeing the pernicious rise in nativism and intolerance and this latest election result in Germany is an indication that Germany is not impervious to this trend. Of course, they have their history always in their immediate rear view mirror, but this is a wakeup call to Germans and all of us that we need to better educate our citizens. so that they don’t succumb to dangerous, divisive and simplistic messages driven by fear and intolerance.

Daniel Fried, distinguished fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Future of Europe Initiative and Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center. He served as assistant secretary of state for Europe from 2005 to 2009.

The bottom line is that the election outcome is not the best, but it’s also not the worst. It shows two things. One, that the populist and anti-liberal wave, which many had optimistically concluded had crested and was in decline in Europe after the French, Dutch, and Austrian elections is still a significant factor in European politics. That is of concern.

The second thing it shows is that despite the fact that Merkel’s party came in first by a long way, the two centrist German parties in power suffered losses compared to their last showing.

John E. Herbst, director of the Atlantic Council’s Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center. He served as US ambassador to Ukraine from 2003 to 2006.

Angela Merkel and her party won the expected easy victory [on September 24] with approximately 34 percent of the vote. But her party, like the Social Democrats, lost ground from the last elections as the far-right Alternative for Germany party picked up over 13 percent of the vote and made it into the German parliament for the first time. With the Social Democrats declaring that they will go into opposition, Chancellor Merkel will have to put together a coalition with both the Free Democrats and the Greens, no easy task.

The impact of this on foreign policy will be felt over time. Chancellor Merkel’s foreign policy has been distinguished by German leadership designed to 1) keep the EU strong and unified; 2) maintain the EU’s relatively open policy on immigration; and 3) help end Russia’s war in Ukraine’s east by pursuing a diplomatic solution protecting Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and maintaining economic sanctions on Russia until the solution is achieved.

If political considerations loom large, the election may prompt the chancellor to move at least a bit to the right on immigration. If the chancellor is unable to establish a coalition with the Free Democrats and the Greens and the Social Democrats agree to join with the Christian Democrats, she may choose to adopt tougher conditions for the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the EU—a key demand of the Social Democrats.

German policy regarding the war in Donbas is least likely to be influenced by the election. While the Kremlin might take some satisfaction in the gains of the AfD, they are certainly unhappy to see the Social Democrats lose ground. The SPD was the most influential voice in Germany for at least easing sanctions on Moscow. No matter who joins the coalition, the chancellor is unlikely to be under domestic pressure to ease sanctions. SPD leader Martin Schulz is stronger on sanctions than Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel. And on the international front, French President Emmanuel Macron is more committed to EU sanctions policy than his predecessor.

While in the short and medium term, the elections will not push Merkel to change policy toward Ukraine and Russia, the long term is something else. While AfD has made major gains on the immigration issue, it is also naïve about Moscow’s revisionism. If the AfD continues to prosper in future elections, it could push Berlin to a weaker policy in the face of Kremlin aggression; but this is not the only possibility.

Alina Polyakova, director of research, Europe and Eurasia, at the Atlantic Council

With the far-right AfD now the third-largest party in the German parliament, [German Chancellor Angela] Merkel will have to do what many other European leaders have been dealing with for years: learn to respond to the challenge on the right without pandering to the extremists’ agenda.

This historic election has shown that Germany is not immune to the far-right populist surge across Europe.

This year’s elections in Europe have revealed the weakness of the center-left, which has basically collapsed in many European countries. With the SPD’s weakest election results since World War II, Germany now fits this pattern as well.

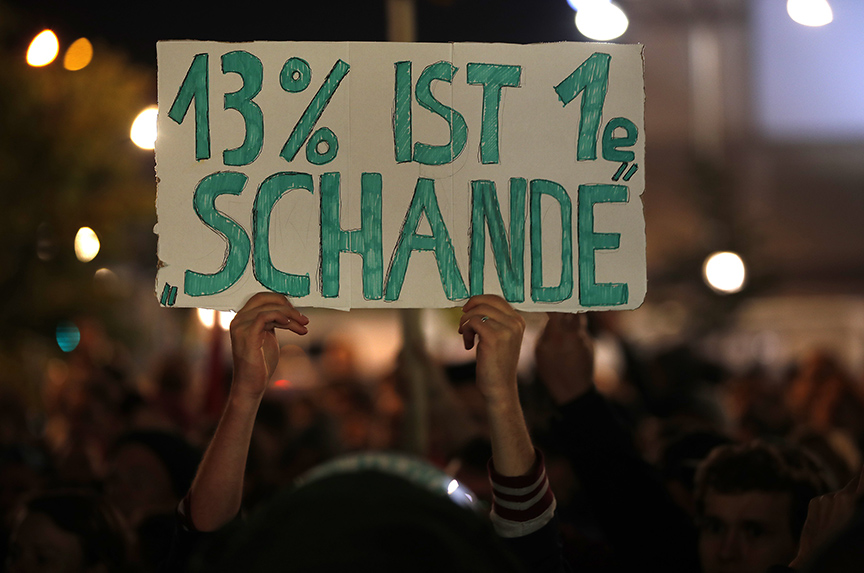

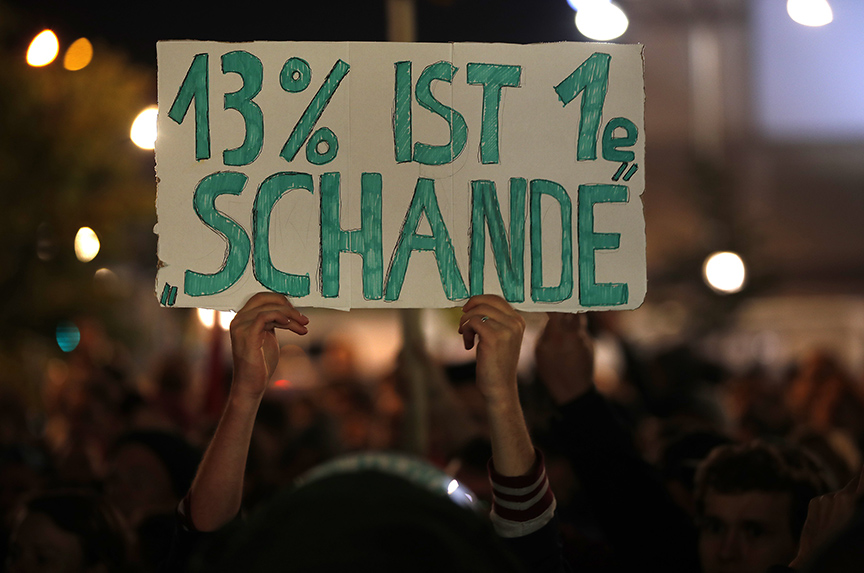

Image: A demonstrator held a poster that read “13 percent is a shame” during a protest against the anti-immigration party Alternative for Germany (AfD) in Berlin on September 24. AfD received 13 percent of the vote becoming the first nationalist party to enter parliament since World War II. (Reuters/Wolfgang Rattay)