A Commentator Close to Putin Writes: Unitary Ukraine is Finished

A prominent Russian business magazine, Ekspert, publishes a lead article this week by two highly placed Russian policy thinkers writing about Ukraine’s southeastern provinces and proclaiming, “We won’t abandon them.” That emotional headline might represent more than just another piece of nationalist opinion-making, for the article’s co-author, Ekspert chief editor Valeriy Fadeyev, has served as an ideologist of sorts for President Vladimir Putin’s ruling party, United Russia. Fadeyev serves on the party’s High Council.

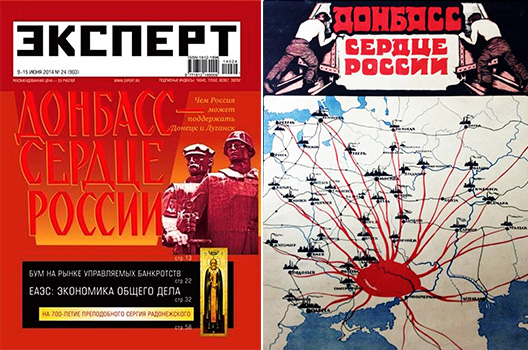

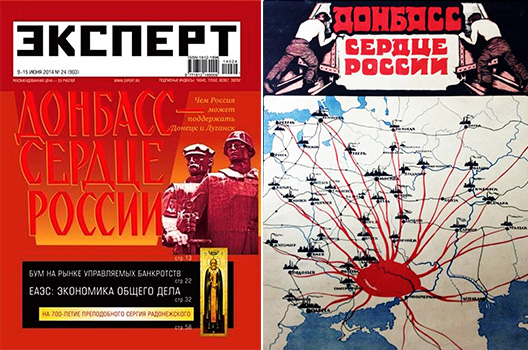

The magazine’s bright red cover declares “Donbas is the Heart of Russia” – an exact reprise of official 1920s Soviet propaganda that underscored the inalienably Russian character of what Moscow calls “Novorossiya,” a zone (including Donbas and other regions of Ukraine) that Czarist Russia conquered in the 18th and 19th centuries. Donbas, or the Donetsk basin, is one of Ukraine’s most densely populated regions – studded with gritty cities whose economies have slumped along with their inefficient, heavy, rust-belt industries (including metals, chemicals, and coal). A famously garish 1921 Soviet poster with the same title as Ekspert’s cover depicts Donbas as a pulsating red heart, pumping industrial goods through blood vessels across Soviet lands.

In proclaiming that Russia now will not surrender its attachment to the Ukrainian provinces of Donbas (Donetsk and Luhansk), the article says that a unitary Ukraine has fallen apart and already cannot be restored within its current borders. That said, Fadeyev and his co-author (chief editor Vitaliy Leybin of Russkiy Reporter) advise that Russia should not invade Ukraine, a threat dramatized by thousands of Russian troop this week’s reported incursion into Luhansk by Russian tanks.

While Fadeyev is no official spokesman, his views reflect and reinforce those of the elite around Putin. A US Embassy cable from Moscow in 2006 described him as having “been a leading figure in defining an ideology for the United Russia party.” In 2012, Putin appointed him to the Civic Chamber, a presidential advisory council.

“The Donbas can never be a part of Ukraine if Ukraine is to be based on a unitary and ethnic-national ideology, write Fadeyev and Leybin. In a certain sense the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics are already a part of Russia, because in fact they are an outpost of the ‘Russian world’ in the evolving conflict,” they write.

Still, the writers caution that Russia should not prematurely recognize the self-proclaimed people’s republics or send in Russian troops. Those steps would escalate an already tense standoff between Russia and the West and compel the United States to pressure Europe into introducing further sanctions, which would threaten international relations and increase Russia’s political, economic and military risks.

A Unitary Ukraine is History

Fadeyev and Leybin echo the Kremlin in blaming Kyiv for the crisis. The rebels of Donetsk and Luhansk made no extravagant demands, did not seriously intend to secede from Ukraine, and simply wanted self-rule, a say in how their budgets are spent and an official status for the Russian language, the editors write. They don’t mention the rebels’ armed seizures of administration buildings and hostages, or the presence of Russian fighters among them. Rather, they write, Kyiv’s “dumb, uncompromising stance, encouraged by the West, did not leave the residents of the east any possibility of attaining their interests through peaceful, political means.”

“Unfortunately the dominant intellectual class [in Ukraine] does not understand” that a unitary Ukraine is no longer possible, the authors write. “The western ideology of building a Ukrainian nation with the pronounced accent of banderovshchyna has become the core of Ukraine’s political life.” (Banderovshchyna refers to the ideas of Stepan Bandera, a World War II-era ethnic Ukrainian nationalist who proclaimed Ukraine’s independence in part by allying for a time with Nazi Germany from Soviet rule.) “A huge part of the population cannot agree with this ideology,” Fadeyev and Leybin write. “Let us remember that some 30 percent of Ukrainians consider Russian their native tongue and it is unlikely that many of these people are followers of Bandera.”

The writers propose that the situation in eastern Ukraine can develop in any of four ways:

- The Russian supported separatist militants can win a military victory and build a viable functioning independent state – Novorossiya;

- The militants win and join Russia;

- Kyiv violently suppresses the rebels;

- Donetsk and Luhansk resume relations with Kyiv.

A rebel victory is not beyond the realm of possibility, posit the Russian editors. They list the militants’ battle successes: ten destroyed APCs, one tank, several helicopters, “hundreds” of Ukrainian army casualties. While the militias aren’t strong enough to take control of more territory, they are capable of continuing local battles.

Russian Fighters to Ukraine

Russia should not send troops into Ukraine, write Fadeyev and Leybin. Plenty of volunteers from Russia, and from Crimea, have gone to Donbas to fight, they say. Far from encouraging Russian nationalists to do so, Russia has moved to restrict that flow, why write, without suggesting how it has done so. In particular, they say, the Caucasus Mountain regions of North and South Ossetia are “brimming with volunteers who remember the help Russia extended to them in 2008.” That’s a reference to Russia’s invasion of Georgia to seize South Ossetia and recognize its independence.

In Donbas, what the pro-Russian militias need more than anything else is good organization, the article says. There are too many hotheads and not enough experienced officers. The rebel leadership must start organizing an orderly and peaceful life for its citizens. First it must help those who have suffered as a result of the “military aggression,” must deliver pensions and subsidies, and protect those most at risk. “This is a very important trust factor” write Fadeyev and Leybin. Not all will receive help, but all should see that the government is acting in a fair manner.

Another way that Russia should be helping is through humanitarian initiatives, say Fadeyev and Leybin. Russians from Donetsk who live in Moscow have collected 100 million rubles (almost $3 million) for humanitarian help in Donbas, they say.

How Russia Can ‘Support’ Donbas — and Absorb it

The Russian state can help pay the subsidies for Donbas residents, the authors say. To further integrate Luhansk and Donetsk into Russia, the government should ease immigration procedures. Russian schools and universities should open their doors without quotas to students from the two provinces.

The poor, outdated state of Donbas’ heavy industry makes the region ripe for easy integration with Russia, the writers say. “Local oligarchs did not bother to upgrade production,” reaching instead for short-term profits, and so Russian investment could step in to modernize plants. The Russian government should facilitate cooperation between Russian business and Donbas companies, they authors write – although they don’t address how the overwhelmingly private owners of Donbas’ industry would feel about consolidation with Russian companies.

Alongside the Russian state, experienced administrators, including Russian émigrés, should all pitch in to rebuild Donbas businesses and their connections to Russia. If Kyiv should cut off banking transactions with the provinces, the authors suggest that Bank Rossii, Russia’s central bank, Bank Rossii should open offices in the region and slowly introduce the ruble.

The authors ignore what an effort like this could cost Russia. They sustain a popular Donbas myth, that the region pays heavily in taxes, receives little from Ukraine’s central government, and so subsidizes the state budget. The official figures say that’s not so. Last month Ukraine’s finance ministry announced that, in 2013, Donetsk province paid the equivalent of $1.4 billion into the state treasury, while receiving $3.52 billion back from Kyiv.

Irena Chalupa covers Ukraine and Eastern Europe for the Atlantic Council.

Image: Russia’s prominent business weekly, Ekspert, leads its edition this week with the declaration that "Donbas is the Heart of Russia." The article, by chief editor Valeriy Fadeyev, picks up the theme from a 1920s Soviet campaign that included the poster at right, which shows industrial goods from Donbas being pumped throughout the Soviet economy. (www.ekspert.com; CC License)