President Vladimir Putin, and hence Russia’s state-run mass media, say the war in eastern Ukraine is a “people’s struggle” by ethnic Russians against attacks by ethnic Ukrainian fascists and Nazis backed by the United States. In the Kremlin’s account, the anonymous, often masked, Russian soldiers in this war are heroic local men, not fighters sent in from Russia.

Maria Turchenkova, a Russian reporter for the Ekho Moskvy (Echo of Moscow) radio station, this week offers one of the most poignant accounts of the Russian soldiery in this war. Tragically, she and a few colleagues got fleeting access to thirty-one Russian fighters in southeast Ukraine only by escorting their bodies back to Russia. Like the Russians’ mission in Ukraine, their return in death was wrapped in secrecy. No officials would show Turchenkova the list of the dead.

Turchenkova titles her report “Cargo 200,” the military code used by the Soviet Union to label transport operations that carried the bodies of Soviet soldiers home from Afghanistan. Her report is lengthy, but it is worth having on the record in English (below), as well as in its original Russian .

Cargo 200 Maria Turchenkova/Ekho Moskvy

It is quiet at the border in Uspenka. On the Russian side, no one is moving. But frontier guards who were bored five minutes ago are, with some astonishment, looking over the truck marked with red crosses and the large numerals “200” painted on its sided. They view it from different sides, taking photographs with their cellphones while the customs guys verify the documents for this cargo.

The verification of papers proceeds formally, but with some palpable tension from the uncertainty of where this “cargo” has come from, and just who has sent it. The truck’s driver, Slava, can’t explain very much. This morning “people whom [he] could not refuse” asked him to drive this truck to Russia, explaining only that it was important that he do so.

Look over the shoulder of the officer, and you see this certificate: “Donetsk Provincial Bureau of the Medical Examiner. … Date: 05/29/2014 … Certified that neither the corpse of Mr. Zhdanovich, Sergei Borisovich, born in 1966, nor the coffin contains items that are prohibited from passage across the borders of Ukraine.”

There are thirty-one such certificates, the same number as the coffins sent from Donetsk two hours ago in this refrigerator-truck. A convoy of three vehicles – a car of police officers, the truck itself, and then a car with us, the journalists — left the city only in the evening. As we got to the border, it was already dark. The light of lanters flickers on the faces of the guards and no one wants to talk. They just wait while the document verification is competed, and keep their eyes on the truck.

Cargo 200 Inside the truck are thirty-one coffins bearing stick-on labels of the “Donetsk People’s Republic.” They carry the bodies of Russian citizens who were killed in Donetsk during the battle for their airport there on May 26. Since the beginning of the military action in April, rumors had been circulating of Russians taking part in the combat around Donetsk, but while they were alive, these people were not seen.

The battle for the Donetsk airport (which still is controlled by the Ukrainian side, even as the city center [is held] by the self-proclaimed DPR) was the most tragic of the entire period of the anti-terrorist operation [launched by Ukraine’s military] in Donbas. The exact number of those killed is still unknown, but according to various sources is not less than fifty people.

The day afterward, reporters were shown showed a pile of bodies in camouflage uniforms. They were laid on the bloodstained floor in the basement of the morgue at the Kalinin in the center of Donetsk city. Many were mutilated, some missing heads or limbs. These were the bodies of those who had been in the Kamaz [a military truck] with the wounded, a truck that came under fire near the airport on the day of the battle. The morgue’s worked continuously, many smoking right in the room. Breathing in the room, and within fifty meters of the entrance, was simply impossible because of the putrid smell.

The morgue was not big enough, so at some point DPR activists arranged for two refrigerated grocery trucks, into which some of the dead were loaded. The trucks’ drivers were here at the morgue, smoking one cigarette after another. They said armed militiamen had stopped them on the road and said simply: “We need the truck.” Now, with their rolling refrigerators loaded with corpses, they were just waiting until the trucks could be released.

Thirty-one Bodies, But Few Names On Tuesday [May 27], local residents started coming to identify the bodies. Some searched for missing relatives, others came to look at lists of the dead, which did not exist. Searching for the bodies of their loved ones in the trucks, where the corpses were stacked one atop another was not possible. So the morgue’s staff prepared mug shots of the dead. By Wednesday, this process had led to the identification of only two bodies – those of Donetsk residents Mark Zverev and Eduard Tyuryutikov.

Until Wednesday night, it remained unclear to whom the other bodies belonged. The mystery was revealed in an unpredictable way. At the end of the day, as we met colleagues in the hotel cafe for dinner, up stepped a man from the circle around Alexander Borodai, prime minister of the self-declared Donetsk People’s Republic. He told us that the next day two trucks would carry the bodies from Donetsk to Russia. And he asked a favor of the reporters – to escort them to the border. He promised to tell us in half an hour, exactly where they would go and who would accompany this “cargo.” He would ask us to tell him whether we agreed to go. We listened, stunned.

This was the first recognition that the battles in the Donbas killed Russian citizens. For two weeks in social media, rumors had circulated that bodies of Russians killed fighting in the east [of Ukraine] had been sent secretly across the border to Russia. But nobody from the DPR would confirm this, much less advertise it.

Now, the leadership of the DPR was asking correspondents to cover this event and escort the convoy, probably because they expected an attack by Ukrainan forces and calculated that the presence of journalists might prevent it.

We utterly failed to understand how this step by the leaders of the Donetsk People’s Republic meshed with the declarations from Moscow that insist that Donbas is a “people’s struggle,” and that deny the participation of Russian citizens in the conflict. And we wondered what reaction to this might be expected from the Kremlin.

In the end we decided to go, and word of the coming event quickly flew around the hotel.

100 Journalists, But No Coverage The next morning, about a hundred journalists from the international media gathered at the morgue. Among them were crews from Channel One and Russia 24 [Russian state television stations], which subsequently reported no news of this event. Alexander Borodai showed up, as did Denis Pushilin, the self-proclaimed speaker of the Supreme Council of the DPR. These two stayed apart from one another, each within his own ring of bodyguards armed with assault rifles, each one talking separately with journalists.

They [Borodai and Pushilin] both said the same: that they would send “Cargo 200,” with its Russian volunteers who had come to support the fight of the DPR’s militia, back to Russia; that they didn’t want any provocation, so the truck would travel with no armed escort.

Variously colored coffins, which DPR activists said had been collected from throughout Donetsk, had been placed at the entrance to the morgue, and journalists speculated whether the bodies had been loaded in them already or not.

The departure of the convoy from the morgue had been planned originally for 1 p.m., and for about four hours, journalists waited for the coffins to be loaded on the truck. The more time passed, the less we believed that the shipment actually would take place. The morgue’s staff moved around with lists of the names of the dead, and even for a couple of moments showed them to reporters, but would not let us photograph or look carefully at them. Besides the press were employees of the Kalinin Hospital, where the morgue was located, watching the scene out of curiosity. And a local resident, Mark Zverev, who came to the farewell.

None of the DPR activists or residents of Donetsk came to take this last opportunity to bid farewell to these “volunteers who came to the defense of the Russian people.” Despite the heavy presence of the press, the event seemed secretive – a tragedy that would be mourned only on the other side of the Russian border.

The loading of coffins into the truck began.

Just then came news that the “Vostok” battalion (one of the disparate militias, and one that has become the strongest in Donbas) had taken over the provincial-municipal government headquarters from the DPR activists. Pushilin and Borodai hastily left. And most journalists rushed to the city center as soon as the coffins were loaded. These reporters later conveyed the news that the dead bodies at the morgue had been loaded and sent to the Russian border.

Surreal But the coffins leaving the morgue were empty.

It seemed that each new turn of the story converted it into a surreal movie script.

As it turned out, the bodies had been moved the previous day to an ice-cream factory. There, they had been loaded into coffins and prepared for shipment to Russia. The truck with the coffins drove into the factory and the gate was closed. In a small space hidden from the view of passersby outside, workers of the factory and DPR activists hastily carried the bodies from the factory’s cold-storage room, gathered body parts, and put the remains first in black bags, then in the variously colored coffins. They smoked, looked around, and loaded the coffins into the refrigerator truck. Meanwhile, other activists painted the sides and the roof of the truck with red crosses and the number “200.”

Three colleagues and I followed the truck from the morgue and it turned out were the only ones for whom this was an interesting and important story. Our interest aroused some respect by the DPR activists. They allowed us to be present while the bodies were loaded, and let us photograph them. One woman told me that she hoped that the Ukrainian military and the “Right Sector” would show humanism and let the truck pass in peace, saying “they are fascists, but there must be something human in them.” I asked if she would be part of the escort. She looked me in the eye and asked, “What, do you want me to be killed?”

We still did not now how we would go, and could not imagine what would happen on the road. It was already evening. We began to worry how we would return to Donetsk. The city had declared a curfew and from 10 p.m. almost no one was on the streets. At checkpoints on the roads, it is unsafe at night. Especially for journalists, who are constantly suspected here of disloyalty or espionage. And then no one knows in which areas exchanges of gunfire could break out. We decided that we would accompany the refrigerator truck until it got dark.

I mentioned this to one of those responsible for sending the truck. And suddenly he offered to leave the vehicle overnight and depart in the morning, so that we could go all the way to the border. It became clear that, for whatever reason, the truck would not be sent without us, the journalists.

That caused some alarm. But we decided just to hope that we would have time before dark and play things by ear.

The Road to Russia About seven in the evening all the bodies were loaded into the truck, the coffins sealed. The activists washed their hands and had a smoke. The nameless Russian volunteers, who had come “to protect Russians” in eastern Ukraine, were seen off on their last journey home in a refrigerator truck from an ice cream factory in silence. In the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic, they did everything that was thought necessary here for the dead Russians. And the DPR stickers on the coffins would have to tell their relatives about their exploits in Donbas. The war continues, and the activists argue at the roadblocks.

We drove through the streets of Donetsk, people glancing indifferently at of the truck, hurrying about their business. In central the activists were being expelled from the Donetsk Regional State Administration and the barricades dismantled.

It was getting dark.

The truck went quickly on the road, not stopping at the militia checkpoints, not slowing down in the towns.

We went to Uspenka. Four kilometers before the border, the truck stopped at a Ukrainian military checkpoint. Soldiers approached the cab per their routine, and the driver handed him the documents for the “cargo.”

As soon as the soldier realized what was inside, his movements became sharp, his voice loud. He called the other soldiers who surrounded the truck, cocked their rifles, pointed them at the truck and ordered the driver to open it. For a long time, the solider did not believe his eyes, looking from the paperwork to the coffins in the truck. He did not know what to do with them. Soldiers noticed our car, and that we “suspiciously” stood at some distance from the truck and watched. Now the rifles were directed at us. Once convinced that we were journalists, they returned to the truck.

-Where are the coffins from? the soldier asked the driver.

Everything was clear without words. The soldiers asked no more questions, checked the documents and ordered the driver to stand on the roadside at the checkpoint. Police officers who were sitting in the first car that accompanied the truck got out and said something to the soldiers. And the truck was allowed through without additional checks.

When we reached the border it was already dark.

No one was warned that this particular cargo would pass through customs. The border guards mechanically checked documents and the truck, according to instructions. They stamped the truck through the border as they would have done a truck loaded with sacks of potatoes.

No one agreed to show us the list of the dead, but we saw a few names on the certificates for the corpses.

Sergey, Yuri, Alexander and Alexander Mr. Sergey Zhdanovich, born in 1966. Information on him already has been out on the internet. On Vkontakte [a Russian website similar to Facebook] there is a group named “Afghanistan: Nothing is forgotten, no one is forgotten.” Someone there writes that he was a retired instructor at the Special Operations Center of the Russian FSB [the former KGB], a veteran of Afghanistan and Chechnya. It is also reported that on May 19 he arrived in Rostov-on-Don for training [on his way to Ukraine] and was killed May 26 in Donetsk.

About Yuri Abrosimov, born in 1982, the certificate for whose corpse we also saw, we have been able to learn nothing.

Some sources on the Internet refer to an Alexander Vlasov and an Alexander Morozov also citizens of Russia, who died at the airport in Donetsk. In comments [on Russian websites] they are called heroes and fighters against fascism; readers are urged to raise their names on the flag and to “throw off a comfortable life and unite to fight the Nazis.”

A letter is circulating on social networks, presented as the last posting by Alexander Vlasov on his VKontakte page. That cannot be verified, as his page has been deleted. The letter reads as follows: “I was supposed to go to Slaviansk any day, myself and two of my friends. I told my mother, explained to my wife, wrote my will, but I had some debts I did not have time to repay. … For a month, I prepared my family. In that time corridors across the border appeared, and people who were not indifferent to me. At the crossing we were supposed to get assault rifles. I, because of my size and strength, [was given] a machine gun, equipment, and so on.”

Further on, he writes that “the channel through Rostov closed. One deputy helped, but it happened … The second campaign covered Security Service of Ukraine.” On his decision to go to Donbas Alexander writes: “Odessa and this whole situation pushed me. I’m a big guy, I cannot sit behind a woman’s back and hide behind [excuses of] the work and children.”

When you’re in Donetsk, you know that the information war being waged in Ukrainian and Russian media has absolutely erased on both sides the border of reality and understanding for what is actually happening now in the east of Ukraine. In reality, only victims remain from this war. Not one of the domestic federal television channels – which for months built up a concrete [public] idea of a genocide against Russians in eastern Ukraine, of the domination by fascists in the west [of Ukraine] – have reported that 31 Russian citizens were killed in Donetsk on 26 May. The channels have not explained the achievement for which they died, or how they got into this war, who opened the “channel through Rostov,” who distributes the weapons – and who meets the coffins with the stickers from the DPR. In the Ukrainian media, these dead are called mercenaries and terrorists.

The history of the first “Cargo 200” sent from Donbas to Russia ended for me and my colleagues on the frontier in Uspenka. And we were the only ones who escorted the Russians who died in the battle for the Donetsk airport, home from Ukraine.

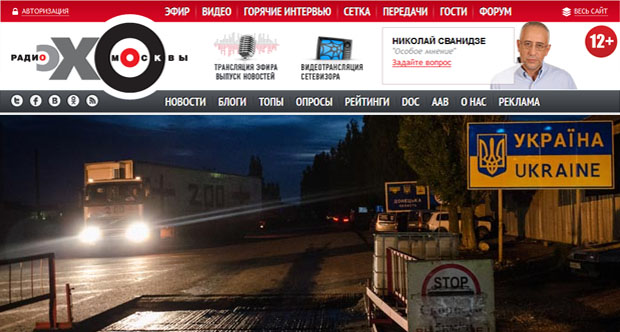

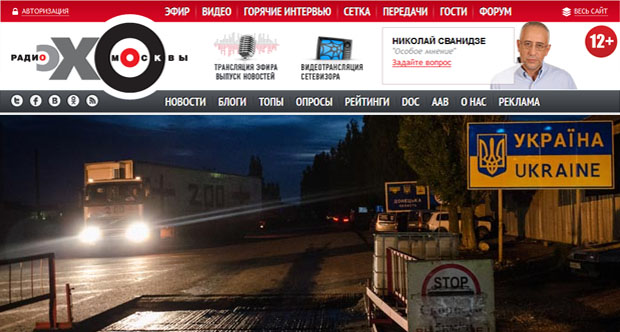

Image: Screenshots from the Ekho Moskvy website show Maria Turchenkova's photo of the "Cargo 200" truck carrying bodies of Russian fighters across the border from Ukraine to Russia.