The debate over sanctions is one of the hottest issues in any discussion on Russian-European relations. Sanctions were first imposed in 2014 by EU member states on Russia, and then by Russia on the EU. In recent months, Russian officials have argued that the EU should lift them, while there have been some signals coming from Europe that ending sanctions may be the best way to return to business as usual.

The debate over sanctions is one of the hottest issues in any discussion on Russian-European relations. Sanctions were first imposed in 2014 by EU member states on Russia, and then by Russia on the EU. In recent months, Russian officials have argued that the EU should lift them, while there have been some signals coming from Europe that ending sanctions may be the best way to return to business as usual.

Both in Russia and Europe, those who call for sanctions’ end say they damage business ties between former partners and cause huge losses for many European enterprises. If sanctions are gone, trade and investment relations between the EU and Russia will resume at full scale, they argue.

This is false, and the main argument used by European supporters of a new reset of economic cooperation with Russia are false.

Europe’s agricultural sector has long been the area most sensitive to the current sanctions regime. Russia claims it lost up to Є20 billion in sales in 2015 alone due to the ban on imports. While that estimate is questionable, it may have some ground: Europeans have already found new markets for their produce. Russian countersanctions had a greater impact on Eastern European nations (the ban affected 41 percent of all agricultural exports from Lithuania, and 18-19 percent of all agricultural exports from Estonia, Finland, and Poland), but they were able to cope. Agricultural products accounted for 30 percent of these nations’ total exports, so the decline has not exceeded Є2.0 billion, while overall EU agricultural exports nevertheless rose by Є7.3 billion in 2015. The resumption of trade won’t dramatically change the EU’s economic landscape—but two other factors are much more important.

First, the Russian economy is in the midst of a crisis; real disposable incomes were down by around 10 percent in 2015, and people are looking for the cheapest food—which generally doesn’t include European products. If brought back to the Russian market, European produce would be uncompetitive because of its high price, and its share in Russian groceries will never be the same as before.

Second, Russia launched a huge import substitution program, which makes the competition even stronger; in addition, many new players—Latin America and China in particular—have entered the market, filling niches that were previously occupied by European producers.

In sum, the lifting of sanctions may increase the EU’s agricultural exports to Russia by 15 to 20 percent over what they were before—but this is not enough to justify such a major foreign policy shift.

The second sector that the West tried to target was the Russian oil and gas industry, which is predominantly owned or controlled by the government. Sanctions targeted high-tech exports which might be used in either offshore oil and gas drilling, or defense and aerospace production. These sanctions are quite effective; some Russian satellite communication projects have been postponed because of the lack of components.

But sanctions are not solely responsible for the 45 percent drop in EU machinery exports to Russia that occurred in 2013-2015. Oil companies had already cancelled their offshore projects, since most were barely paying off at $100 per barrel. Additionally, the Russian state is now trying to strip the energy sector of much of its cash to cover the budget deficit—so the lifting of sanctions would not boost the demand for such equipment in Russia. Moreover, fixed investments in Russia fell by more than 8 percent in 2015 and will decline by more than 10 percent this year, so a policy change will not bring much relief to Europeans.

In addition, the fall in oil prices provoked an overall slump in Russian sales of high tech products, passenger cars, and many durable consumer goods. Since November 2015, Russians have spent more than 30 percent of their incomes on food alone, so there is little room to boost the sales of European goods there (and there were never any restrictions on importing EU-made industrial consumer products to Russia), even if sanctions are lifted.

The third and most important aspect of the Western measures was the ban on new loans for a huge portion of Russia’s banks and corporations. Russian companies, both financial and non-financial, were forced to repay up to $160 billion in loans that came due in 2014 and 2015, decreasing their capacity to invest in new projects. This was a severe blow, since prior to the occupation of Crimea, Russian companies received more loans from Western financiers than from Russian banks.

The end of the sanctions regime could be good news for Russians, since it might contribute to a dramatic improvement in the country’s current account balance, if only two obstacles were absent from the overall picture.

First, two years ago, Russia was a country with 1.3 percent GDP growth, the stock market RTS index was at 1450 points, and significant investment opportunities were fueled by $107 per barrel of oil. Russia today is a country with a 3.7 percent GDP decline for 2015, the RTS index has fallen to 650 points, and oil is selling at $30 a barrel—all of which are causing many foreign companies in Russia to terminate their operations. Many Russian borrowers missed the margin calls and their covenants have been violated, so few Western banks will now provide them with new loans. Even if EU authorities lift the ban, one will most likely not see a great surge in Russian financing in coming years.

Second, while EU leaders convene every six months to discuss sanctions on Russia, their American counterparts do not. Even if Brussels allows EU banks to resume lending, they will, in doing so, violate US restrictions and expose themselves to American sanctions hitting all their dollar-denominated operations, which are crucial to any global financial institution. Therefore, no single EU bank will provide loans to Russian banks and companies on the US sanctions list—and it looks like this list is even longer than the European one.

Lifting the EU’s sanctions on Russia would be senseless from a purely economic point of view: it will not restore cooperation between the EU and Russia to its previous condition. From this point of view, the only real reason to consider such a move is the resumption of Russia’s economic growth, which might make Russia a useful European partner once again. But for the Europeans to be mislead by false promises and to subjugate their political principles to illusionary economic benefits would be a huge and inexcusable mistake.

Vladislav L. Inozemtsev is a Visiting Fellow at the Atlantic Council and a professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

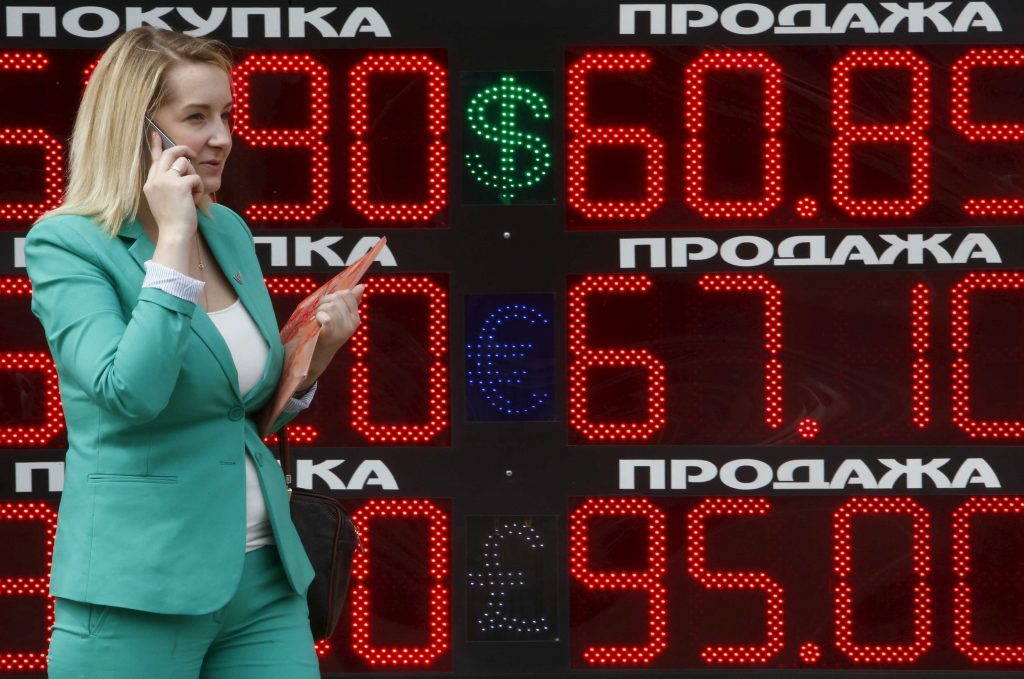

Image: A woman talks on the phone while walking past a board showing currency exchange rates of the US dollar, Euro and the British pound (top-bottom) against the rouble in Moscow, Russia, July 28, 2015. Russia's growth prospects deteriorated sharply midway through last year, when an existing slowdown was compounded by Western economic sanctions over the Ukraine conflict and a collapse in the price of oil, the country's main export earner. REUTERS/Sergei Karpukhin