What’s striking about the debate over President Obama’s plan for a punitive strike against Syrian President Bashar Assad is the extent to which it centers on countries other than Syria. There’s a reason for this. A concept that has had a long, significant though subtle influence on U.S. foreign policy is at work again: credibility.

What’s striking about the debate over President Obama’s plan for a punitive strike against Syrian President Bashar Assad is the extent to which it centers on countries other than Syria. There’s a reason for this. A concept that has had a long, significant though subtle influence on U.S. foreign policy is at work again: credibility.

The foundational assumption — certainly the subtext — of many arguments for hitting Assad is that America’s reputation is on the line. It’s said that many bad things will happen if Obama folds: Various friends and allies will doubt America’s pledges to protect them; adversaries (Iran, North Korea, Hezbollah, Al Qaeda and others), smelling weakness, will act with impunity.

“Credibility” has great power in national security debates. It conveys strategic sagacity by using historical analogies. (Neville Chamberlain at Munich is a staple.) It warns of consequences that transcend specific nations or issues. It points to the “big picture” and to complex interconnections. It invokes the United States’ unique responsibilities for maintaining global order.

In reality, the credibility gambit often combines sleight of hand with lazy thinking (historical parallels tend to be asserted, not demonstrated) and is a variation on the discredited domino theory. This becomes apparent if one examines how it is being deployed in the debate on Syria.

Obama made a bad decision by publicly, and needlessly, warning a brutal strongman that the United States would resort to military force were he to use chemical weapons. With the White House having announced that Assad had done just that, Obama appears tangled in his own red lines.

But he should not make another mistake now just because he made one earlier. Yet that’s what those who invoke credibility in effect recommend because they don’t explain convincingly why it’s important for him to prove his resolve in this instance. They present credibility as an end in itself, not as a means to achieve a desired outcome, which is what it is.

The concept often serves as an all-purpose rationale. The result is that it can permit the past to dictate the future and give choice and prudence, the essentials of sound statecraft, short shrift.

Consider Syria in this light, focusing on desired outcomes. The president hasn’t explained precisely what he intends to accomplish with a limited strike. He has specified that it’s not about changing the balance on Syria’s battlefields (which favors Assad), let alone ousting the regime. But such an operation won’t end the slaughter. Those killed in the Aug. 21 chemical attack account for only 1.4% of Syria’s death toll over the last two years, which exceeds 100,000. The operation Obama proposes would leave Assad with abundant means to continue killing, even if he loses important military assets.

Nor would the opposition be bolstered. Indeed, Assad, who will retain the military advantage, might target with even greater ferocity the groups that urged the U.S. to punish him.

Further, it’s misleading to depict the president’s plan as limited. Even a “tailored” attack against what is a chaotic, fragile and war-ridden country could have unanticipated and destabilizing consequences — ones that the United States would be unable to contain short of deeper involvement. But the war-weary American public is in no mood for another long war. Adding to the instability of Syria and its neighborhood would scarcely add to America’s credibility.

Those who favor a strike against Syria invariably argue that the president must act because otherwise the Iranian leadership will conclude that it can call his bluff and build nuclear weapons. That’s a plausible scenario, but not the only one. Another is that an American attack on Syria could convince Iranian hard-liners that nuclear weapons are an essential deterrent. Or they might conclude that if Obama decides not to strike Syria, he would have to attack an Iran on the verge of building the bomb. The stakes would be incomparably higher and the pressure on the president much greater, precisely because he failed to enforce his red line in Syria.

Although those who invoke credibility pretend otherwise, it’s impossible to predict which outcome is most probable. Given this uncertainty, the logic for attacking one country in order to send a message to another is shaky.

The appeal to credibility has a long history in U.S. foreign policy. Consider Vietnam. We had to keep escalating and not quit — so it was said — because the Soviet Union and China would detect weakness and test the United States in various places (Berlin, Taiwan). Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, the argument went, had to learn that President George W. Bush was not bluffing about using force to dismantle his (supposed) stockpile of weapons of mass destruction; it was not just about Iraq but also about North Korea and other “rogue states.”

Speaking of North Korea, would an American strike against Syria increase or decrease the (admittedly) slim chances for a deal that ends in denuclearization, or convince Pyongyang that nuclear weapons are an essential insurance policy?

Credibility is now trying to shape the Syria debate. Its logic is no sounder today than it was in bygone years. But it’s no less dangerous.

Rajan Menon is a professor of political science at the City College of New York/City University of New York and a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

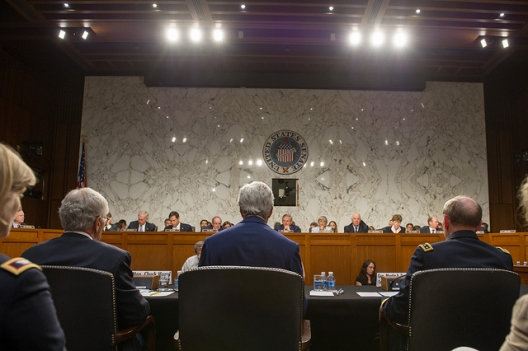

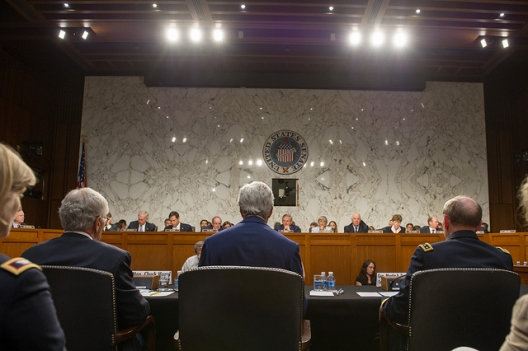

Image: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin E. Dempsey speaks along with Secretary of State John Kerry and Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel during a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing at the Hart Senate Office building in Washington D.C. Sept. 3, 2013 (Photo: Flickr/CJCS/Daniel Hinton)