EU’s Economic Ties to Russia Slow its Pace, But New Steps Show Unity With US

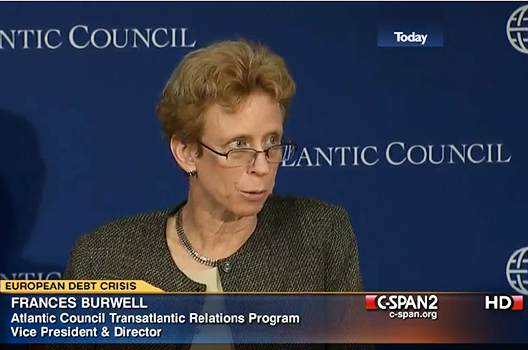

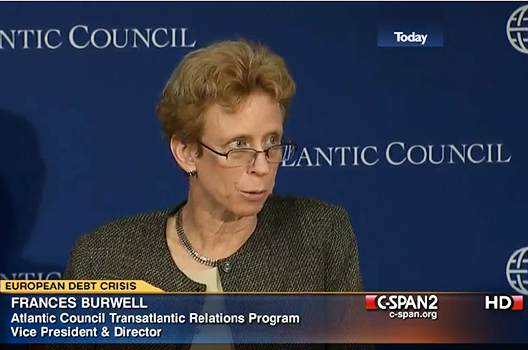

This week’s European sanctions on Russia are “a game-changer” in applying the European Union’s first restrictions on a relatively broad sector of trade, says the Atlantic Council’s Fran Burwell. While the sanctions are shaped to avoid directly damaging key European economic interests, and are not as broad as many US policymakers seek, Burwell said they also are likely to cause secondary effects in Russia that will tend to drive more investment out of that country. In the West’s effort to pressure Russian President Vladimir Putin to halt his attacks on Ukraine, the EU’s new sanctions align Europe with the United States in targeting key political and business allies of the Russian leader.

The EU struck Putin’s closest cronies for the first time today, ordering a ban on transactions or travel on the continent by two of them – businessman Arkady Rotenberg and banker Yuri Kovalchuk – who had been sanctioned by the US government. US-European planning on any new steps against Russia is likely to hit a lull during Europe’s August vacation period and the installation in September of a new European Council president and administration, Burwell noted. As the US works to maintain pressure on Russia, “We need to not let these sanctions become a competition between the United States and Europe as to who can be tougher,” she said.

Tuesday’s announcements of new “US and EU sanctions were totally coordinated, and the timing of this was meant to send a message to Russia that ‘we are unified,’” Burwell said.

Among the points Burwell made in an interview at the Council were these:

On the ‘Cuba Effect.’ As the US asks Europe for broader sanctions, a little-noted drag on the process has been many Europeans’ belief that the United States locks itself into sanctions regimes that can run beyond their usefulness. Many Europeans “You can just hear it in the conversations, in which Europeans will say, ‘The Americans have had sanctions on Iran for how many years? And sanctions on Cuba for my entire lifetime!’ So our credibility in getting sanctions ended is not especially high.”

On Europe’s new banking sanctions and their impact. “Russian state banks will no longer be able to raise money in European capital markets. That’s really significant in that this is where they have raised capital. These Russian institutions say that they can go elsewhere, and that’s probably true in the short run, but this makes it much more difficult for European companies that were thinking of investing in Russia to get financial backing.” Even though the sanction technically “just says that you cannot buy their bonds [in Europe], I think it’s going to make everyone allergic to dealing with these state-run banks. You are seeing in Europe a hesitation … where companies are pulling back because they believe that there will be trouble or restrictions in the future. So the sanctions become wider than what they legally are, because of the psychological impact, the expectations they create.”

On Europe’s greater stakes, and greater pain, in sanctioning Russia. “We have to remember that Europe, and particularly Germany, have a much more significant stake in trade with Russia than we do. … We Americans have $38 billion annually in trade with Russia; the EU has $400 billion. And Germany has a large share of that. In Germany, as well, it is not just a few big companies. In the United States, it tends to be Exxon-Mobil, and Chevron and a few others, primarily in the energy sector. In Germany, the connections with Russia are much more widespread – the provision of all sorts of goods and services. … And I think we are going to see retribution against European companies. We’ve already seen Polish meat products banned from Russia because they are considered ‘unhealthy’. I would not be surprised to see European companies suddenly discover that they have tax problems in Russia.”

On Europe’s change of mood: It wasn’t just the destruction of the Malaysian airliner. “We’ve seen a real change in Europe’s mood, partly because of the shoot-down of the airliner, but even more from the Russian response afterward. I think there was an expectation, particularly among the Germans, that the Russians would do the decent thing, secure the area, and make sure that those who shot down this aircraft would be brought to justice. … The Germans had an expectation that this would be a moment when Putin would pull back. … Merkel had been looking to keep Putin engaged during the crisis, but I think came to the conclusion that the time for caution was now past.”

On Russia’s vulnerability to sanctions. Burwell noted that a key climbdown by Putin came in his acceptance in late May of the legitimacy of Ukraine’s presidential election. That “was a point when European and US sanctions had started to bite. It was shortly after we saw the first figures of capital flight from the Russian economy during the first quarter of the year. … What Europeans would say is that through these sanctions we hope that, if not Mr. Putin, then his allies will see that they really don’t want to take Russia down this economic path. … Moreover, these sanctions will damage the personal economic interests of Putin and his allies because these state-owned banks that have been sanctioned have been important in helping these elites who have profited most from the Russian economy. Penalizing them could help bring the moment in which they say ‘this is something that we really don’t want, either for our country or ourselves.’ This is what the Europeans hope for.”

On the unpredictability of Moscow’s response. “Of course, it’s unclear what the Russian government’s response will be, given the very mixed messages we have seen from Putin. It’s quite striking that, since the airliner shoot-down, there apparently have continued to be serious armaments continuing to move across the border in Ukraine, when the lesson should have been learned that when you do this you can’t control how they may be used.”

On Germany’s cooperation with the US over Russia despite tensions with Washington. “The German government and the chancellor in particular have been able to compartmentalize issues in the relationship with us. For example, she’s made very clear that she is in still very much in favor of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, while also making very clear that she is not very mollified by our response to date on the NSA surveillance in Germany and the CIA espionage scandal. So I would say that the Germans and we are perfectly capable of continuing to work” on issues that demand cooperation despite the tensions on surveillance and intelligence issues.

James Rupert is an editor at the Atlantic Council.

Image: Screenshot via C-SPAN