Europe’s two major parties suffered considerable losses to smaller parties—both Euroskeptic and pro-European integration—in elections to the European Parliament from May 23 to May 26.

While the center-right European People’s Party (EPP) and center-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) remain the two largest parties in the European Parliament, both parties suffered double-digit seat losses, according to preliminary results. The big gainers of the night were the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE), which benefited from the debut of French President Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche party, and an array of far-right Euroskeptic parties who made gains throughout Europe.

The Brexit Party exploited the internal division among the British Conservative and Labour parties to secure first place in the United Kingdom, while in Italy, Matteo Salvini’s far-right League Party also finished first. Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party bested French President Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche party for first place in France, projected to receive twenty-two seats to Macron’s twenty-one. Several Green parties also made considerable gains in countries such as Ireland, Germany, and France, vaulting their grouping to double-digit seat gains.

Going forward, parties with MEPs must now form political groupings within the Parliament. For many of the established parties, this is already set in stone, but many of the far-right players have yet to establish a firm home. It remains to be seen if the British Brexit Party and the Italian Five-Star Movement, for instance, will find the partners in seven member states necessary to form a group.

European leaders will meet at a summit on May 28 to begin selecting a recommendation for the new president of the European Commission, which the new European Parliament must approve. According to the spitzenkandidaten system first used in 2014, the new Commission president should be the “lead candidate” from the political grouping that won the most seats in the election, in this case the European People’s Party and German MEP Manfred Weber. There has been speculation, however, that the European heads of state could ignore this system, given the poor showing of EPP and internal division within that party over the suspension of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party. The growing number of outsider parties could also force European leaders to select a compromise candidate in order to secure enough support to pass the EU Parliament, as the EPP and S&D no longer control a majority of seats between them.

An emerging fight between the European Parliament and heads of government could just be the beginning of a long tussle with a body that now reflects much more Euroskepticism and political diversity than the leaders of Europe.

Atlantic Council experts react to the results of the European Union Parliamentary elections:

Benjamin Haddad, director of the Atlantic Council’s Future Europe Initiative:

“As predicted, the political landscape in Europe is scattered and will make coalition building more complex in the next parliament. For all the focus on the rise of populism, mainstream parties still represent the vast majority of elected officials.

“In France, Marine Le Pen wins her second EU election in a row with Macron’s En Marche a close second. While in no way a victory for En Marche, this score does confirm Macron’s institution that the divide between ‘progressives’ and ‘nationalists’ would shape the French (and European) political landscape. This analysis is vindicated by the collapse of France’s two establishment incumbent parties: the Socialists and the Republicans.

“One other important aspect of this election is the strong showing in France and especially Germany of the Greens, especially among millennial voters. Environmental issues are taking an increasingly central stage in European politics.

“The hardest is yet to come. With no clear majority in parliament, EU leaders will have to agree in the next days on who will take the key positions for the next five years. According to projections, the EPP will get [around] 178 seats and S&D 152. That’s seventy-three fewer seats than in the previous parliament. A far cry from the majority needed in this 751 seats assembly. The time when the two parties could divide seats is over and the upcoming EU summit might signal the end of the spitzenkandidaten formula.”

Frances Burwell, a distinguished fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Future Europe Initiative:

“The big story is that the Parliament will be so divided, with no obvious governing majority. And given the diversity of the parties in terms of outlook and policy priorities, it will be difficult to make coalitions among the party groups so that the Parliament can push its own views in the legislative process. Any coalitions are likely to be temporary and issue-specific. As a result, Parliament will become a very uncertain and unpredictable actor.”

Bart Oosterveld, C. Boyden Gray fellow on global finance and growth and director of the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program:

“The fracturing of the European Parliament is challenging, but there continues to be a solid pro-European project majority. The stronghold that the center-right and left had on decision-making in Europe was also something that populist groups responded to, so I don’t see its demise as something purely negative.

“Turnout increased across the board and the elections were of more interest to voters than the European Parliament elections have been at any time in the past two decades.

“While center-left and right parties lost their traditional dominance, gains were distributed mostly to the generally pro-European Greens and Liberals. Hard-right, anti-Europe/immigration parties did not make meaningful gains in terms of seats in the European Parliament.”

Jörn Fleck, associate director in the Atlantic Council’s Future Europe Initiative:

“The decades-old ‘grand coalition’ of Christian Democrats and Socialists is history in the European Parliament too, following a trend of electoral losses for the mainstream parties in the member states in recent years.

“But despite the hype about the gains of nationalists, populists, and Euroskeptics, the next European Parliament will remain solidly pro-European. Shifts away from the Socialists and to a lesser degree the Conservatives have largely benefited the Greens and Liberals. The new parliament will be a more exciting, complex, and more political legislature, requiring greater coalition-building, compromise, and competition among several pro-European party families. Democracy and competition about the European project’s future vision, political agenda, and policy is back with a bang at a European level.”

David A. Wemer is assistant director, editorial at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

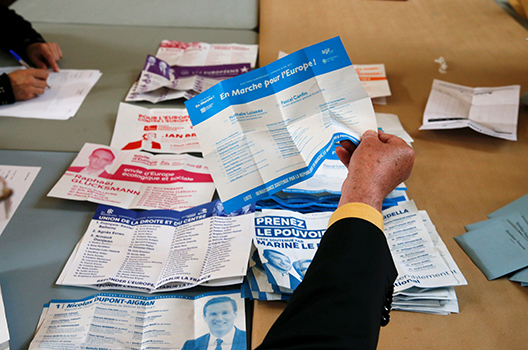

Image: An election official examines ballots as vote counting starts in European parliament elections in Cambrai, France, May 26, 2019. (REUTERS/Pascal Rossignol)