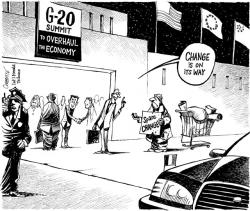

Will this weekend’s G20 summit really be “Bretton Woods II?” The answer from Europe (like the U.S.) seems to be no.

The European press is largely doubtful that the meeting will result in an overhaul of the global financial system. Going into the Washington gathering of the world’s largest economies, most analysts believe that political and practical limits on the implementation of a coordinated rescue plan will linger after the meeting adjourns.

In the UK, the Economist’s blogs are busy with commentary on the summit. The publication’s editors called the meeting a “last chance at a positive legacy” for President Bush, while Richard Baldwin cautioned that empty statements may do more harm than good:

Governments and central banks have stopped their financial systems from bleeding to death by applying tourniquets, but the longer-term solutions are unclear. Meanwhile, governments are getting themselves in deep holes of various types—fiscal, regulatory, current account, and concerning the politics of nationalization. Exit strategies are nowhere to be found.

Moreover, national leaders seem unprepared for the next round of difficulties that will arise as the global recession grows and financial crisis spreads to emerging markets. Economically and financially, there is a clear sense that things are spiraling out of control again. In this fragile situation, a bland G20 summit declaration could do more harm than good. Signs that our great leaders can’t agree on priorities will signal to investors that the future will resemble the recent past.

Gideon Rachman seemed even more pessimistic than Baldwin, titling his latest FT column “The Bretton Woods Sequel Will Flop.” He writes:

[L]ike most sequels, Bretton Woods II is not going to be nearly as good as the original. The first conference gave birth to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Its successor will be duller and less consequential.

Rachman notes that the Bretton Woods conference had the advantage of two years of planning and was necessary following the total destruction of the international order during World War II. He also questions motives, arguing that European excitement about the conference is based at least partly on “the idea that the age of American primacy is over – and a new multilateral era is dawning.” Rachman states that the G20 does recognize shifts in global power by including countries such as China and India, but he adds: “[B]ringing them into the system is no guarantee of success. The more voices around the table at Bretton Woods II – and the more equality there is between them – the harder it will be to reach agreement.”

In the FT Economists’ Forum blog, Richard Portes flatly states, “Expectations for the G20 meeting on November 15 are excessive. It will not agree on changes to the institutions of global governance, nor will it come up with an ‘n-point plan’ for dealing with the crisis.” He argues that the summit should focus on raising confidence. G20 leaders need to convince the world that a show of unity on principles is better in the short-term than a detailed plan of action. He concludes: “What is feasible for the meeting on November 15? To agree on principles, though not in the full detail set out above; and to establish working groups with fixed timetables, all ideally coming to detailed conclusions by spring 2009, when the new U.S. administration should be ready for decisions.”

But the question remains, is another Bretton Woods needed? If so, the world would be well advised not to hold its breath for such a rearrangement this weekend.

And what about Russia? Martin Gilman of the Moscow Times argues: “[U]nlike most of the other G20 members, Russia is a large creditor country. With the third-largest foreign exchange reserves in the world, the country has a natural role in any discussion of the reform of the global monetary system.” He expounds:

The IMF also has a very limited pot of money — about $250 billion — relative to the size of the problems faced by its members. Short of a major increase in quotas or shares, the fund will need to turn to creditor countries such as China, Japan, Russia and Saudi Arabia to obtain parallel financing for countries in need. But that leads to the problem of legitimacy.

The core of the problem is the political issue of who controls the IMF. The G7 has about 45 percent of the voting rights and Western countries almost 60 percent, yet the seven largest creditor countries in the world, except Japan, are not in that group. The anomalies are striking. Russia has a quota less than Italy, China and France, and the United States retains veto power.

If Gilman is willing to concede that control of the IMF is political, it seems strange that he would expect Western leaders to expand Russia’s IMF voting rights in light of all the recent tensions (and mistrust) over Georgia, missiles, sinking stocks, et cetera. Russia and China certainly do need to be incorporated into the international financial system, but like Portes’ points above, these issues are of a much longer-term scope; attempting to solve them this weekend would be far too haphazard.

Euractiv also picks up on the increasing importance of emerging economies, writing that the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) are calling for stronger representation in the World Bank and the IMF. Deutsche Welle similarly notes the desire among developing economies for a stronger voice.

In an EU-27 statement, member states have agreed upon “common principles … to build a new international financial system.” They have called on Washington to enact better regulation of credit rating agencies and accounting practices, reduce excessive risk-taking in the financial sector, and help the IMF restore and revive the global financial system.

Both the German and the French presses seem to view the conference as a stepping stone to further reform. The center-left Süddeutsche Zeitung writes: “Redesigning the global financial system is a historic challenge, and not one that can depend on the results of a single conference. One should see the Washington D.C. summit as the beginning of a process.” French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner similarly stated, “I am not expecting big recipes coming out of the G20 meeting. But I am expecting, particularly from the new administration, certainly a road map.”

Gordon Brown, the earlier hero of the financial crisis for introducing his three-pronged rescue package (adding liquidity to financial markets, buying up preferred stocks in banks, and guaranteeing interbank lending), urged the world’s leading economies to implement coordinated tax cuts in order to curb the effects of a global recession.

The overall message for this weekend’s G20 meeting seems to be that world leaders should avoid hasty moves enacted only to project the image that progress is being made. Rather than trying to create and implement a massive overhaul to the global financial system in just days and with little preparation, the summit should be used to agree on principles and lay the groundwork for future coordinated action and institutional reform.

Peter Cassata is an assistant editor with the Atlantic Council.

Image: G20Cartoon.warsawbiopic.jpg