In the late 1970s, Egyptian Foreign Minister Boutros Boutros-Ghali couldn’t figure out why African summit meetings unanimously voted against Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel. So he decided to sprinkle his delegation with intelligence gumshoes for the next summit in Sierra Leone in 1980. Their mission: Find out what kind of chicanery was going on behind the scenes.

All the heads of state were staying in the same hotel in Freetown, which made sleuthing a lot easier. Boutros-Ghali wasn’t surprised by the results. Each one received a Gucci briefcase with $1 million. There was one exception: Hastings Banda of Malawi. He got $100,000 in a brown paper bag. All courtesy of Moammar Gadhafi.

The Libyan dictator staged his Sept. 1, 1969, coup with exquisite timing. The CIA station chief was taking his time sampling the Michelin Guide’s three-star restaurants as he drove through France to Marseilles. The British MI6 chief was on home leave in the United Kingdom. And King Idris was on his yacht in the eastern Mediterranean, soon to land in Turkey for medical treatment.

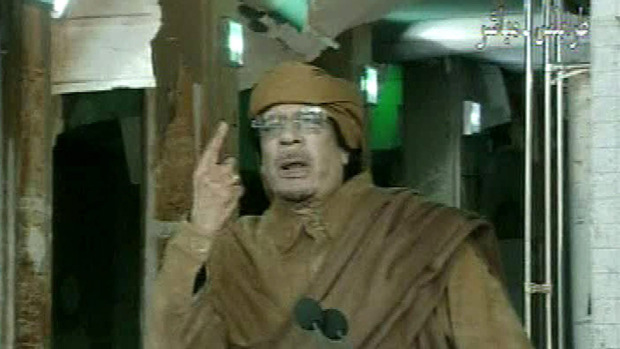

For this journalist who interviewed Gadhafi six times over the past four decades, the Libyan absolute dictator is a megalomaniac manic depressive. In his first year in power, he endeared himself to most Libyans by showing up at the back door of a hospital disguised in rags as a poor, stooped old woman. He explained in a high-pitched voice that he needed help as he thought he was dying. He was told to come back in the morning and the door was slammed in his face.

Next day, Gadhafi closed the hospital and sent the staff to look for work elsewhere.

His popularity soared.

Then, with a mix of lavishly funded propaganda, subversion, assassination and terrorism plots, he went on to interfere in the internal affairs of no less than 40 countries over his four decades in power.

He dispatched a Libyan expeditionary force with armored personnel carriers and tanks by ship to Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. By the time the ship docked in Dar, Idi Amin had taken off into a golden exile in Saudi Arabia.

Gadhafi plotted coups and counter-coups all over sub-Sahara Africa. Armed with petrodollars, he established himself as Africa’s supremo. One great news photo shows him on a large couch in Tripoli with four African heads of state — two on each side — with a bored Gadhafi reading a newspaper.

Before the 1973 Yom Kippur war, he flew to Cairo several times in his private jet without advance notice, raced through the VIP lounge and jumped in a taxi to see his favorite Egyptian newspaper editor Mohamed Heikal, close friend of the late dictator Gamal Abdel Nasser. On one such caper, Heikal had just returned from Beijing. He regaled Gadhafi, whose historical knowledge started and stopped in high school, the story of China’s "Long March" led by Mao Zedong in 1934-35. This gave Gadhafi his next idea.

No sooner back in Tripoli than he organized a "Long March" on Cairo. This was designed to provoke President Anwar Sadat into a more muscular Pan-Arab foreign policy. Thousands were mobilized in eastern Libya and sent off to march to Cairo. Sadat’s intelligence service followed all the planning — and his elite troops were deployed to turn the marchers back whence they came.

In 1974, after an interview with Gadhafi, this reporter was on a Swissair flight about to take off for Geneva when Libyan plainclothesmen came aboard and shouted my name. They ordered me off the plane. I explained I had a bag in the hold. They said, "No worry. Plane no leave without you."

As we drove off the tarmac they explained "Colonel Gadhafi wants to see you immediately." I protested I had just seen him the day before.

"Yes, we know, but he wants to see you again." It took 30 minutes to get to his headquarters at Azizia barracks.

"Yesterday," the interpreter said listening to the chief, "you said Sadat might invade Libya. Now you must tell me everything you know."

I gave him my word of honor I knew nothing about Sadat’s plans, only that I knew he was more than a little angry at the colonel’s lavishly funded subversive activities in Cairo. And that I wouldn’t be surprised if Sadat retaliated.

After giving Gadhafi my word of honor on his Koran, he relented and let me return to the airport. By the time I got back aboard, the aircraft had been held at the gate three hours. It was mid-June and more than 90 degrees. Angry dagger looks from fellow passengers would be an understatement.

In 1993, at the end of a two-hour interview, I said, "Now you’re going to tell me what really happened with Pan Am 103." He dismissed everyone in the tent about 60 miles south of Tripoli. And in halting English he reminded me that a "peaceful Iran Air Airbus on its daily flight across the gulf from Bandar Abbas to Dubai, with no other planes in the sky, was shot down in July 1988 by the USS Vincennes, killing 290 people. … You claimed it was an accident but no one in our part of the world believed you. So retaliation was unavoidable."

He went on to explain that the Iranian intelligence service subcontracted part of the counter-blow to one of the Syrian intelligence services, which, in turn, turned to Libya for assistance. "We knew this would be a big blow," he said but claimed they didn’t know what, specifically, the target was.

Pan Am 103 was blown out of the sky over Scotland in December 1988, killing 259 on the aircraft and 11 on the ground. Gadhafi eventually turned over two wanted intelligence service suspects. One was cleared and the other released on compassionate grounds two years ago. Turned out he wasn’t dying of cancer. It was allegedly part of another oil deal with BP.

Gadhafi forked over $2.7 billion as a settlement with the families of 270 killed, or $10 million per victim.

After the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003, Gadhafi thought he might be next on President George W. Bush’s hit parade. He quickly surrendered his entire secret nuclear weapons program, bought from Pakistan’s infamous Dr. A.Q. Khan.

But now, cornered in an Orwellian nightmare, he praised President Barack Obama’s African ancestry and Muslim proclivities and blamed everything on a common enemy — Osama bin Laden. He still has a chemical-biological arsenal. And this mentally sick head of state could be tempted by an apocalyptic Gotterdammerung.

Arnaud de Borchgrave, a member of the Atlantic Council, is editor-at-large at UPI and the Washington Times. This column was syndicated by UPI.

Image: Feb__22__2011LO_1205834cl-8.jpg