Secretary of Defense Bob Gates has rightly been hailed as a great public servant, a stellar Secretary, and a constructive partner to Secretary Clinton. He also frequently makes the case for building up civilian international affairs capacity in his most prominent policy speeches. Yet a number of his proposals applying this policy in fact undercut civilian authorities and capabilities. Foremost among these is the idea for new, permanent, shared DOD-State resources and authorities for conflict prevention, post-conflict reconstruction, and security assistance.

Secretary Gates has an article in the latest issue of Foreign Affairs that builds on his December letter to Secretary Clinton, proposing joint funds between State and Defense. It is the latest salvo in a long-running debate over how to manage security assistance programs, how to fund contingencies, and how to integrate short-term defense requirements with longer-term development and diplomatic considerations.

He Who Pays the Piper Calls the Tune

Temporary authorities in the last few years (1206, 1207, CERP) have been devised and implemented, driven by two wars and a global counter-terrorism strategy. DoD’s ability to get funding for these efforts on a large enough scale trumped concerns about the appropriate roles of State and USAID. These short-term authorities should not be the long-term pattern.

First, Gates proposes a shared-pool of funding to address conflict prevention. This is the “day job” of the Department of State and USAID and should be funded through accounts controlled by the Secretary of State. DoD’s rightful awareness of the importance of “Phase 0” operations does not change the fact that the most important tools in conflict prevention are diplomatic and development ones, not military ones. Providing some of the funding through DoD committees and with one key in the pocket of the Secretary of Defense would distort the decision making on when, where, and for what purposes such funding should be applied. There is a crying need for more flexible funding that can be applied quickly where there is a new risk or opportunity and DoD is to be commended for its ability to wrest those kinds of authorities from Congress. State and USAID need additional, un-earmarked funds that can be spent quickly, including on security sector assistance activities appropriately undertaken by the DOD.

The second proposed pool is for post-conflict stabilization and reconstruction. The U.S. military knows better than anyone how critical it is to get this right because the cost of failure in blood and treasure are too high. DoD has done important work on developing doctrine for how to manage these complex environments and has put up seed money for State and USAID to operate (Section 1207). It has always been clear, however, that these resources and authority were temporary, and that reconstruction and stabilization should be a civilian activity funded through the Department of State. Recent budget requests have shifted the funding permanently to State through a Complex Crises Fund. Congress obliged last year, and so it should remain. Any CERP funding for DoD should include clear purposes related to military activities and a requirement to coordinate with civilian officials. The close relationship between S/CRS at State and DoD on doctrine and deployments indicates that these funds would be used to address instability and to expand civilian operations in areas where DoD has an interest.

Gates’ shared pools proposals provide the mirage of easy money but would come with too many strings. The Secretary of State should remain the lead on foreign policy activities and maintaining control of funding ensures she, and her successors, can exercise that authority. The larger problem with these proposals is the continued perception that the role of diplomatic and development activities is supporting military operations. In reality, in most places, most of the time, the United States will not have a military presence in countries where we will have an interest in ensuring or securing the peace.

Burying the Lede

Secretary Gates’ proposal is most serious on the subject of training and equipping of foreign militaries. This is the focus of the Foreign Affairs article, suggesting that the other two proposals discussed above may be red herrings, for which DOD does not expect to gain administration support.

No one disagrees with DoD’s comparative advantages in helping build partner militaries and the value of military contacts with counterparts in a world of coalitions and ungoverned spaces. And no one disagrees that security assistance is a vital part of foreign policy and must be considered as part of our overall relationships and carefully reviewed for impact on human rights. Traditional train and equip missions, such as those done through foreign military financing, balance these two facts by being funded as foreign assistance, overseen by the Department of State, and implemented by the Department of Defense.

Creating funding outside this arrangement and moving to a “dual-key” would undermine this balance. No amount of consultation or even concurrence requirements outweighs the influence that resources and personnel bring to policy debates. Shared pools between unequal partners cannot guarantee State’s foreign policy leadership when DOD will likely still provide the majority of funds and staffing.

The Section 1206 program and the new proposed joint pool were designed for rapid-reaction and to be available for unforeseen needs. But they were also clearly in response to DoD views that FMF funding is insufficient, inadequately flexible, too slow, and not targeted to the priorities DoD would emphasize. Instead of working to support an increase in the State Department’s budget and capacity as his speeches indicate, in this case Secretary Gates is proposing to institutionalize the resource imbalance and enshrine in law DOD’s dominance over security assistance decisions. If greater flexibility is needed, perhaps that needs to be achieved in a reworking of current FMF authorities, not by creating yet another pool of funding.

Conclusion

In the last 10 years, DoD has expanded its mission and resources to fill the gaps it perceives in civilian capabilities. Even DoD cites the importance of the vastly less expensive and more effective civilian solutions in areas like post-conflict stabilization. So why does DoD find an empty space to fill? There are a variety of political answers: Congressional mistrust of civilian departments, insufficient Administration leadership, uncertainty about overseas nation building. Yet most important is that Congress finds it far easier to fund the military due to a sense of military competence and a commitment to providing whatever is necessary for “defense” activities.

This reality, however, is not something simply to be managed or worked around. Nor should the extra costs just be tolerated amid other expensive DoD budget items or merely ineffective programs be overlooked. Having DoD perform civilian tasks is harmful to our national security interests.

- Mixing authorities and funding in this way prevents rational division of labor between Defense and State based on the more efficient and effective allocation of resources and on comparative advantages of each.

- It also confuses appropriate military and civilian roles. It is important to ensure that U.S. overseas engagement has a strong civilian face; greater military presence does not always serve our long-term interests well. Optics matter especially in combating violent extremism and fighting insurgencies.

- In a world of limited budgets, continuing to concentrate funding at DoD risks crowding out the development of civilian capabilities. Once created, DoD programs and missions are nearly impossible to downsize. The lack of civilian resources begets lack of management capacity and predictably undermines the requests for resources. This vicious cycle ultimately precludes the development of capabilities that are needed far beyond the scope of DoD’s areas of operation.

- Capabilities – people and money – combined with strong DoD interest will exert outsized influence on decisions about where and why assistance should be provided. This undermines the authority of the President and Secretary of State to direct foreign policy.

DoD should be continuing efforts to build civilian capacity and supporting increases in the international affairs budget instead of continuing to creep into mission areas for which it claims to have no interest or expertise. Greater civilian capacity is the best way to mitigate the risk that DoD will be called to respond to a conflict that threatens us. Secretary Clinton should engage Secretary Gates seriously in discussions about the appropriate management of security assistance policy, without being distracted by the proposals for conflict prevention and conflict response funding pools. She should thank Secretary Gates for his support for the international affairs budget and enlist him in her rounds in Congress. This would give Gates the chance to use his well-deserved reputation to make a major shift that would cap off his lasting legacy.

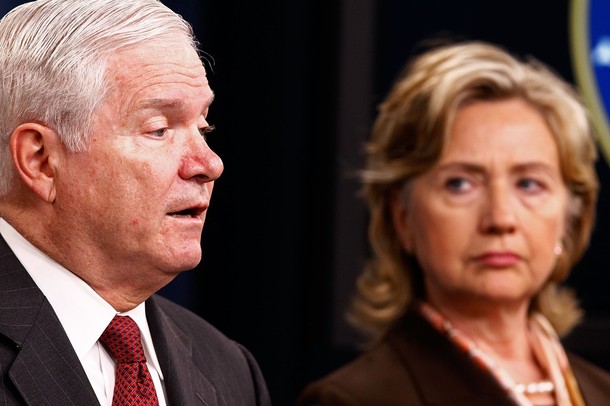

Laura A. Hall is a Council on Foreign Relations International Affairs Fellow at the Henry L. Stimson Center. This essay was published at the Budget Insight blog as "Relying on the Kindness of Others: A Risky Partner-Building Strategy." Photo credit: Getty Images.

Image: gates-clinton-closeup.jpg