The Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) is at a crucial juncture. They have momentum on the ground, but they risk losing the chance to restore a unified Libya if they acquiesce to an Egyptian proposal for what amounts to a ceasefire in place, backed by Russia. This could lead eventually to a dismembered Libya, with the GNA without effective control over its most vital national resources. Instead, the GNA can insist on continuing its relationship with a broad international coalition and talks among Libyans convened under auspices of a United Nations mediator.

Meanwhile, the international coalition of which the United States is a member should back the Tripoli government in asserting its national sovereignty. This is the necessary step toward political and economic unity under a democratic constitution. The alternative, being pushed by the latest proposals emanating from Cairo, is not Libya for the Libyans. It would be spheres of influence for Egypt, Turkey, and Russia.

Libyans have an existential stake in the future of their country. While they have often practiced politics badly, it is noteworthy that the democratic experiment launched in 2011 succeeded for awhile against very heavy odds. Democratic rule is hard to achieve everywhere, but Libyans lacked the advantages of experience in self rule. This was true when Libya was part of the Ottoman Empire for centuries, and it was even more the case under Italian colonial rule for several decades. Even as an independent state, first under King Idris and then under Muammar Gadhafi, self rule had virtually no meaning for most Libyans.

It is right to challenge Libyan leaders to overcome their narrow aspirations to power and do a better job of making constructive political compromises. It would be wrong to expect them to do this without more international support for state institutions and less foreign interference in Libyan domestic politics. American friends of Libya should recall the hard struggle of our own independence leaders and that it took us about seventy years and a horrible civil war to finally reach a lasting consensus upon which to build our political future.

A number of countries have vital national interests at play in Libya. Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, other African neighbors, and nearby Western European countries feel the threat of instability in Libya. Rightly so. They would suffer the consequences of terrorists thriving on Libyan territory and finding ready access to them through porous borders, just as they already incur harm through arms smuggling and uncontrolled migration. Conversely, these countries have the most to gain in various ways by political progress and economic prosperity in Libya.

Other players in the Libyan drama have less at stake in terms of vital interests but may have considerable reasons to be engaged in terms of their national self image, international influence, and reputation. The United States, Russia, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, the European Union, and the United Nations would head that list. All have been involved to some extent since Libyans rose against Gadhafi in 2011. Libya is significant for them, but that fact does not excuse actions based on narrow self interest. Less obvious, but also true, it does not excuse inaction by the United States and failure to aid in bringing Libyans to the table where they could work out a political consensus to break the current stalemate and then to begin the necessary tasks of governance.

Despite its troubled history and its current, deep problems, Libya has the potential to become a powerhouse of regional development. Libya has a favorable location at the center of the Mediterranean region where it was one of the most productive parts of the Roman Empire and even produced two Roman emperors. It has important connections to both Africa and the Arab World. For some time to come, its oil and gas reserves will remain important both to the prosperity of its region and to reduce Western Europe’s need for Russian gas. By contrast, it is now a source of trouble to nearby neighbors in every direction. The contrast between future opportunity and current dire reality should motivate interested governments to help restore the promise rather than exploit the realities of conflict.

My sympathy with Egypt’s concern for its direct security interests and long Western border does not overcome my view that the Egyptian government appears to have chosen the wrong tool for defending its national security and enhancing the economic interests it might share with Libya. As for Russian policy toward Libya, I have no sympathy at all. Russian policy seems designed to maintain chaos, restore some of the security cooperation it enjoyed during the Gadhafi period, prevent the full development of Libyan energy flows to Western Europe, and get even with NATO and the United States for what it views as an embarrassment for Russia in 2011. As a former US ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, I question the strategic rationale for overextending the UAE’s influence and risking the firmness of its national security partnership with the United States on matters of far greater importance to UAE interests. The same might be said for our NATO ally Turkey.

Western European nations have much to lose from continued Libyan instability and much to gain from a reversal of fortunes. They should end bickering among themselves and play the kind of leading role that would gain them long lasting benefits while reducing many potential threats. If they do, I believe they will find other governments, such as the United States and key Arab governments, ready to support well considered European initiatives.

The United States government is right to demand that other states should not be free riders hoping to benefit from a leading role by Washington. However, limiting the US role to fighting terrorism risks the periodic resurgence of the kind of threat that was all too ominous when the so-called Islamic State had established its power in the heart of Libya along the Mediterranean. A whack-a-mole approach is short sighted. Safe havens for terrorism and other forms of lawlessness would emerge from the spheres of influence that Egypt, Russia, and Turkey hope to gain. What has happened in Syria is instructive.

Libyans are less resistant to a more active US role and to continued United Nations mediation than they show themselves to be with other external actors. The United States has some unique assets to offer which other external partners and the Libyans themselves would welcome. For starters, Washington decision makers should raise the Libyan issue higher on their agenda for talks at the top level with counterparts in Cairo, Abu Dhabi, Ankara, and key European capitals.

David Mack is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs.

Further reading:

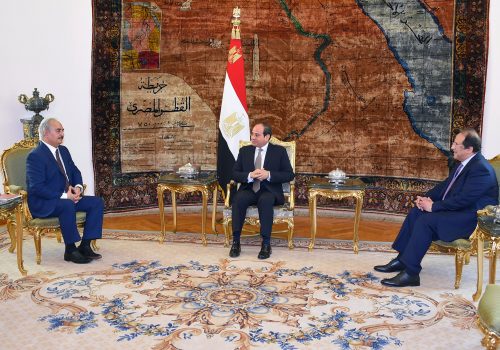

Image: Libya's internationally recognised Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj speaks during a news conference with Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan (not pictured) at the Presidential Palace in Ankara, Turkey, June 4, 2020. Murat Cetinmuhurdar/Turkish Presidential Press Office/Handout via REUTERS