The WikiLeaks scandal isn’t even a pale carbon copy of the Pentagon Papers 39 years ago that accelerated America’s Vietnam defeat.

But even then there was nothing that wasn’t known by the war correspondents covering Vietnam. Deception and disinformation were part of the U.S. arsenal. And the daily afternoon military briefing was known as the "Five O’Clock Follies."

This was followed by the civilian briefing that was largely ignored by the war correspondents. Yet this is where one found out about the latest Vietcong atrocity — such as wiping out an entire village to cower neighboring villages into total compliance.

Apart from a handful of reporters, the bulk of the U.S. press corps in Vietnam was anti-war. The self-hating American became a well-known syndrome. And Daniel Ellsberg, the former Pentagon official who gave The New York Times a mountain of pilfered top secret documents in 1971, was a self-avowed anti-Vietnam war pacifist activist. Worshiped by the media, Ellsberg quickly assumed iconic status.

Ellsberg, a former U.S. Marine, photocopied a 7,000-page top secret report on the Vietnam War while working for the Rand Corp., a defense think tank, and gave it to the Times. He then went underground before his arrest. The charges and trial for treason were dropped when it became known agents working for the Nixon White House had broken in to his psychiatrist’s office looking for evidence against him.

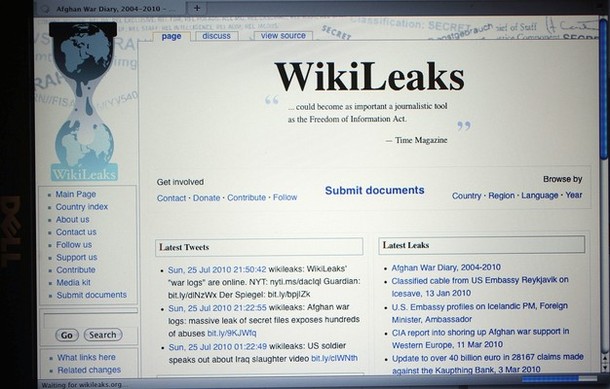

Ellsberg was among the first to conclude that the gusher of wikileaks of stolen classified material isn’t a patch on his secret trove four decades ago — and the impact it had on speeding up an end to the Vietnam War. But all the returns on that assessment aren’t yet in. WikiLeaks may well accelerate the current disenchantment with the Afghan war.

Julian Assange, the Australian front man for WikiLeaks, has a huge organization behind his campaign to end the war, which so far has seen 1,200 Americans killed. In Vietnam, some 58,000 lost their lives. WikiLeaks has 800 part-time anti-war activists with an extended network of 10,000 and some 80,000 supporters. The common denominator is anti-war activism.

The 93,000 documents on six years of war in Afghanistan take the narrative to last December when U.S. President Barack Obama’s new strategy (with 30,000 additional troops) was barely getting started. But that wasn’t relevant for WikiLeaks’ anti-war agenda. The aim clearly is to drive up anti-war numbers at a time when opinion polls give Obama’s war the support of less than half the people.

WikiLeaks thought it had hit the jackpot with the documentation of Afghan civilian casualties. Perhaps they didn’t read how many French civilians were killed during the 1944 Normandy invasion (city of Caen leveled) to liberate France. In almost every war, there are more civilian casualties than military.

The most troubling part of the classified documents is the ambivalent aspect of Pakistani support for the war, now backed by 44 nations under the U.N., NATO and U.S. flags. Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency originally created the Taliban (Student) movement to fill the vacuum left by Soviet troops when they abandoned Afghanistan, defeated after 10 years of guerrilla warfare.

Civil war then broke out and the Taliban, armed and trained by ISI, conquered the country and established cruel, feudal rule under Mullah Muhammad Omar, a cleric who had lost one eye as a guerrilla fighter against the Soviets. Omar then welcomed Osama bin Laden back after he was expelled by both Saudi Arabia and Sudan.

Bin Laden had kept a register of all the Arab and other Muslims who had volunteered to fight the Soviets in the 1980s. He then sent them messages to return to train for the next round, this time against American imperialism. Omar allowed bin Laden to set up a score of training camps. The Saudi leader was convinced he had brought down the Soviet empire because nine months after the last Soviet soldier left Afghanistan, the Berlin wall collapsed. This conviction led to the 9/11 plot against the last "evil empire" — the United States.

ISI has long been ambivalent about the Taliban they originally engineered. The feudal theocracy of Omar, next to which the Spanish Inquisition’s Tomas de Torquemada was benign, spawned another Taliban movement, this time turned against the Pakistan establishment. Its insurgents got within 60 miles of Islamabad before the army decided this was the real enemy and poured tens of thousands of regular troops into a campaign to beat them back to the border tribal areas. But once there, the army found it increasingly difficult to separate "good" Taliban from "bad" Taliban, the new enemy.

Pakistan’s strategic thinkers and decision makers have never believed that the United States and its allies would see their Afghan campaign through to the successful construction of a new democracy, or at least the semblance of a viable, moderate regime. That would require five to 10 more years — with considerable loss of blood and a commitment of several hundred billion dollars for a country the size of France.

The U.S. Congress is beginning to conclude that those borrowed billions are needed at home where at least $1 trillion is needed for long-postponed infrastructure projects. Tired allies also want to go home. Dutch fighters are leaving in mid-August, recalled by their own parliament. Same story for the Canadians in 2011.

This leaves U.S. and British troops under the command of U.S. Army Gen. David H. Petraeus to hit Taliban sufficiently hard to move them to the negotiating table. Defeating them is a bridge too far — and would require many more troops. The only U.S. imperative would be to guarantee al-Qaida wouldn’t be allowed back by a new Taliban regime. That would be the least difficult to achieve. Omar lost his country due to bin Laden’s 9/11 attacks against the United States.

Denials notwithstanding, Pakistan’s powers that be can see a reformed Taliban agreeing to guarantee the non-return of al-Qaida. These negotiations, initiated by Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah, have been sputtering off and on for 2 1/2 years. Al-Qaida no longer needs their Afghan bases. Radicalizing Muslim youth everywhere courtesy of the Internet has far more appeal than an obstacle course in Afghanistan to train would-be suicide bombers.

Arnaud de Borchgrave, a member of the Atlantic Council, is a senior fellow at CSIS and Editor-at-Large at UPI. This article was syndicated by UPI. Photo credit: Getty Images.

Image: wikileaks_0.jpg