The Islamic Republic of Iran has a new president: Hassan Rouhani. There has been a lot of talk about Rouhani’s supposed political moderation and pragmatism, just as in 1982, there was talk that Yuri Andropov’s supposed fondness for jazz indicated a liking for the West in general, and the possibility that there would be a thaw in Soviet-American relations. In Andropov’s case, such thinking proved to be too optimistic. Similarly, there may be no justification for optimism in Rouhani’s case either; both because Rouhani has been a mainstay of the Islamic revolution in Iran, and because the Iranian president has significantly less power than many Western observers seem to think he does.

The Islamic Republic of Iran has a new president: Hassan Rouhani. There has been a lot of talk about Rouhani’s supposed political moderation and pragmatism, just as in 1982, there was talk that Yuri Andropov’s supposed fondness for jazz indicated a liking for the West in general, and the possibility that there would be a thaw in Soviet-American relations. In Andropov’s case, such thinking proved to be too optimistic. Similarly, there may be no justification for optimism in Rouhani’s case either; both because Rouhani has been a mainstay of the Islamic revolution in Iran, and because the Iranian president has significantly less power than many Western observers seem to think he does.

Let’s start with an examination of Rouhani’s political background. As Lee Smith notes, Rouhani was an early follower of the Ayatollah Khomeini and has held a number of positions in the Islamic government. Despite hopes that Rouhani might be willing to compromise regarding Iran’s quest for nuclear power, he has “ruled out a halt” to uranium enrichment. This does not necessarily mean that there will not be any give on the issue in the future, but those hoping for some signs of moderation regarding this issue have to be at least somewhat disappointed in Rouhani’s unwillingness to cater to their hopes.

Rouhani has intrigued observers by making noises about his desire to form better ties and closer relations with the United States. However, he won’t engage in direct talks with the United States in order to actually bring about better ties. To be sure, it would be politically difficult for him to immediately call for such talks, and it is possible that he will employ back channels in order to communicate with American officials. But while it is fine and good to entertain such aspirations, one cannot necessarily count on them to be fulfilled.

It is important to note that there are limits to Rouhani’s supposed “moderation.” Noting Rouhani’s good standing as a member of the theocracy, Thomas Erdbrink reminds us that according to a number of analysts, Rouhani’s “first priority will be mediating the disturbed relationship between that leadership and Iran’s citizens, not carrying out major change.” He also reminds us that Rouhani has used his image as a moderate and a pragmatist “to find practical ways to help advance the leadership’s goals.” Those goals, of course, are highly immoderate in a host of ways.

Rouhani had the opportunity once to employ moderation and pragmatism in order to help bring about genuine political liberalization in Iran. In 1999, student protests erupted in Iran demanding greater political and social freedoms for the populace. But Rouhani moved in lockstep with the rest of Iran’s fundamentalist theocracy in order to crush those protests. Sohrab Ahmari quotes Rouhani’s own words:

At dusk yesterday we received a decisive revolutionary order to crush mercilessly and monumentally any move of these opportunist elements wherever it may occur. From today our people shall witness how in the arena our law enforcement force . . . shall deal with these opportunists and riotous elements, if they simply dare to show their faces.

The Revolutionary Guard and basij militia helped Rouhani prove as good as his word, as they attacked, imprisoned, and killed protesters. Those imprisoned were tortured by the regime’s henchmen. Need it actually be mentioned that no genuine moderate would have stood for or countenanced such human rights abuses?

One might have hoped that a moderate, pragmatic new Iranian president might be inclined to work to change the nature of Iran’s relationship with Israel. However, Rouhani has proven to be as provocative as any Iranian hardliner by calling Israel a “wound” on the Muslim world. Iranian state TV claims that Rouhani was misquoted, but state TV also showed a segment which undermined its denials. And is anyone really surprised to find out that the public statements of the new Iranian president sound a lot like the public statements of the previous Iranian president when it comes to Israel?

Even if we assume that Rouhani is a moderate, and is committed to genuinely reforming and liberalizing the sociopolitical environment in Iran, the fact of the matter remains that as president, Rouhani will not have the power he needs in order to achieve those goals. Political power in Iran resides in the office of the supreme religious guide, and the current supreme religious guide, Ali Khamene’i, is no one’s idea of a moderate. Indeed, he cannot afford to be a moderate, lest he undermine his own political position.

As Bill Samii wrote back in 2004, Khamene’i never enjoyed great prestige as a theologian, and his promotion to the position of grand ayatollah was a “hasty” one, designed to give him credibility as the country’s supreme religious guide. The Iranian constitution had to be amended so that the supreme religious guide no longer needed to be a marjaeh taqleed, or “source of imitation” for devoted Muslims. This was a fortunate political development for Khamene’i, as he was a middling cleric and as attempts to make him a marja met with surprisingly stiff opposition:

Theoretically, the Islamic republic system (vilayat-i faqih, leadership of the supreme jurisprudent) is legitimate when a Grand Ayatollah who is recognized as a source of emulation (marja-yi taqlid) serves as the Faqih (jurisprudent). Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Shirazi, like many others, did not accept Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as a source of emulation. According to “Human Rights in Iran” (2001) by Pace University’s Reza Afshari, Shirazi was “indignant” over Khamenei’s efforts to be recognized as the supreme leader and as a source of emulation. Shirazi, who died in late 2001, apparently favored a committee of Grand Ayatollahs to lead the country. Shirazi was not the only senior cleric to suffer for questioning the legitimacy of Iran’s political setup and its leading figure. One of the best-known dissident clerics was Grand Ayatollah Hussein Ali Montazeri-Najafabadi. Others were Grand Ayatollah Hassan Tabatabai-Qomi and Grand Ayatollah Yasubedin Rastegari.

Because Khamene’i’s religious credentials have never been held in high regard amongst members of the Iranian clergy, he has been subjected to significant expressions of disrespect by other members of the Iranian clergy. Khamene’i has been forced to compensate for his weak theological standing by always being the most hard-line Iranian politician in any setting. Back in the 1990s, Khamene’i made sure that he was seen as a loud and frequent advocate on behalf of Bosnian Muslims during the political upheaval in the former Yugoslavia. He has also sought to shore up his religious authority and position by frequently advocating on behalf of the Palestinian people in the context of the Arab-Israeli conflict. When back in 2008, a minister close to former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad said that the Iranian and Israeli people could be friends despite their political differences, Khamene’i strongly dissented, saying “[i]t is incorrect, irrational, pointless and nonsense to say that we are friends of Israeli people.”

Khamene’i is a hardliner because he has to be. Being a hardliner is about the only way that he can make up for his less-than-prestigious standing amongst the religious clergy. Even if Rouhani is determined to moderate Iranian politics and cause Iran to deal with the international community in a more pragmatic fashion, Khamene’i will oppose him. He knows no other way.

Obviously, one hopes that all of this pessimism about the next four—and perhaps eight—years of Hassan Rouhani’s presidency is misplaced. One hopes that does indeed succeed in moderating the tone and substance of Iranian politics at both the domestic and international level. But there is evidence in Rouhani’s background that he is not the moderate he claims to be, and even if he is, there are built-in obstacles to Rouhani’s success. We can hope for moderation and pragmatism in Iran, but we may end up seeing more of what we have seen during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency.

Pejman Yousefzadeh is an attorney in the Chicago area. He writes on law and public policy at his eponymous blog.

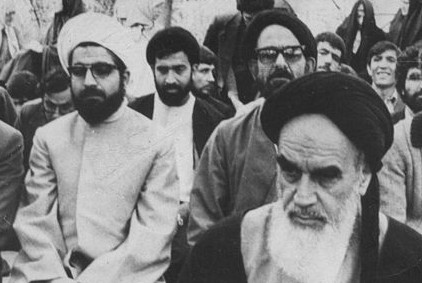

Image: Hassan Rouhani with Ayatollah Khomeini (photo: Wikimedia)