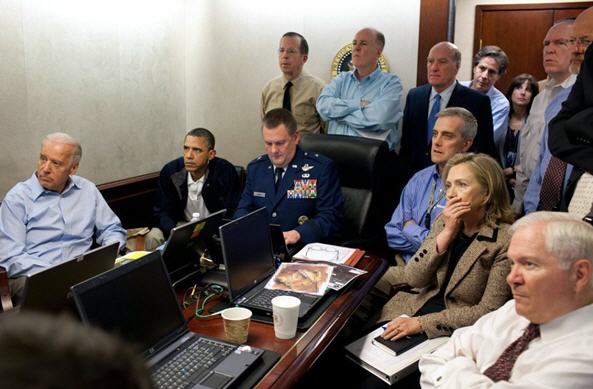

CFR’s Micah Zenko asks, “How Risky Was the Osama bin Laden Raid?”

The question, of course, is interesting on the first anniversary of that raid because Obama administration officials are making the rounds touting how “gutsy” the call was and a new Obama campaign ad featuring former President Bill Clinton declaring, “Suppose the Navy Seals had gone in there, and it hadn’t been bin Laden. Suppose they’d been captured or killed. The downside would have been horrible for [Obama].”

Zenko surveys the history of such raids, failed and successful, and finds little basis for this assertion.

Throughout recent history, US presidents have authorized limited military operations that were mixed successes or outright failures. In most instances, the president neither suffered a noticeable decline in public support nor faced sustained criticism among elite observers for the decision. Policymakers and pundits generally refrain from criticizing presidents, military commanders, and the armed forces for failed operations.

Zenko provides several examples–and I commend the piece to you in full to read them–but the first is the best:

In perhaps the riskiest military misison authorized by a U.S. president, Jimmy Carter ordered the unsuccessful hostage rescue operation in Iran (Desert One) on April 24-25, 1980, which resulted in eight U.S. soldiers killed and no hostages freed. In the initial stages of planning, the Delta Force commander, Colonel Charlie Beckwith, admitted to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “the probability of success is zero and the risks are high.” According to aNewsweek article on June 30, 1980, the Pentagon estimated that as many as fifteen of the fifty-three hostages as well as thirty of the U.S. special operation forces would be killed or injured in a successful operation.

There is no evidence, however, that Carter’s decision-making negatively impacted the mission. An internal review conducted by the Pentagon found that “the decision process during planning and the command and control organization during execution of the Iran hostage rescue mission afforded clear lines of authority from the President to the appropriate echelon,” and, “the command and control arrangements at the higher echelons from the NCA [the President and Secretary of Defense] through the Joint Chiefs of Staff to [Combined Joint Task Force] were ideal.”

Although Carter was aware of the potential costs of the rescue attempt, he believed, according to a senior adviser, “Ending the crisis—once and for all—became the major factor in the president’s decision-making.” And the American public agreed: two-thirds approved of Carter’s decision to authorize the ill-fated mission. Republican presidential candidate George H.W. Bush was the most outspoken supporter: “I unequivocally support the president—no ifs, ands, or buts…He made a difficult, courageous decision.” Afterward, the president’s approval ratings, previously plummeting, actually stabilized—until he was easily defeated by Ronald Reagan.

I was but 14 at the time and just at the beginnings of my political consciousness–which was awakened by the Hostage Crisis and the 1980 campaign. I was no fan of Carter’s presidency and thought his handling of the hostage situation spineless (positions which I’ve somewhat revised given the advantages of maturity and hindsight). But, even in the wake of the disastrous mission, my sense was “Thank God he finally did something.” I think that was the consensus view.

To be sure, the president deserves credit for both making a difficult decision against mixed advice from his senior foreign policy team and, especially, for ramping up the hunt for bin Laden, which had been all but called off under his predecessor.

In fairness, Jimmy Carter didn’t have to deal with the 24/7/365 outrage machine that exists today. There was no Rush Limbaugh, no Fox News, no blogs, and no Twitter. But even in today’s toxic political climate, most Americans would have applauded a SEAL raid to get the man behind 9/11 even if it had ended in catastrophe.

We seldom blame presidents for bold actions that go wrong. We despise them for appearing weak and indecisive.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council.

Image: obama-situation-room-bin-laden-raid_0.jpg