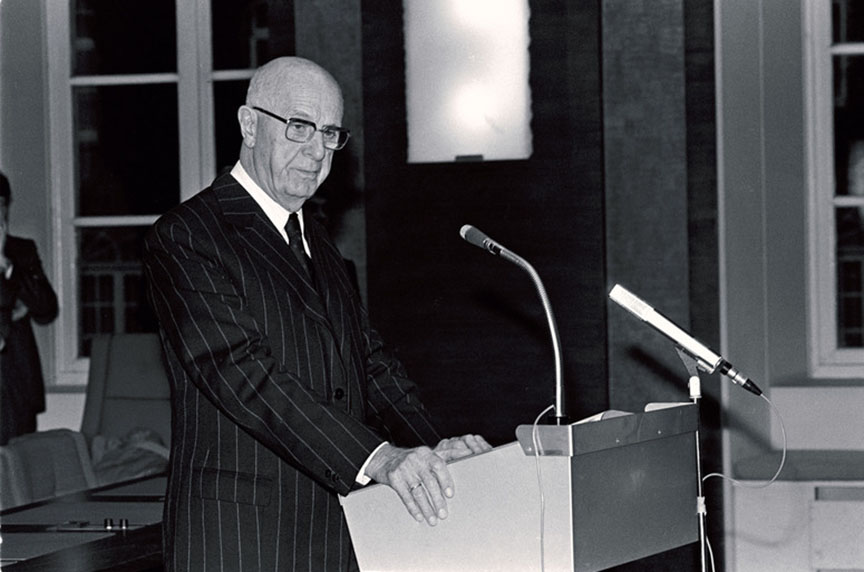

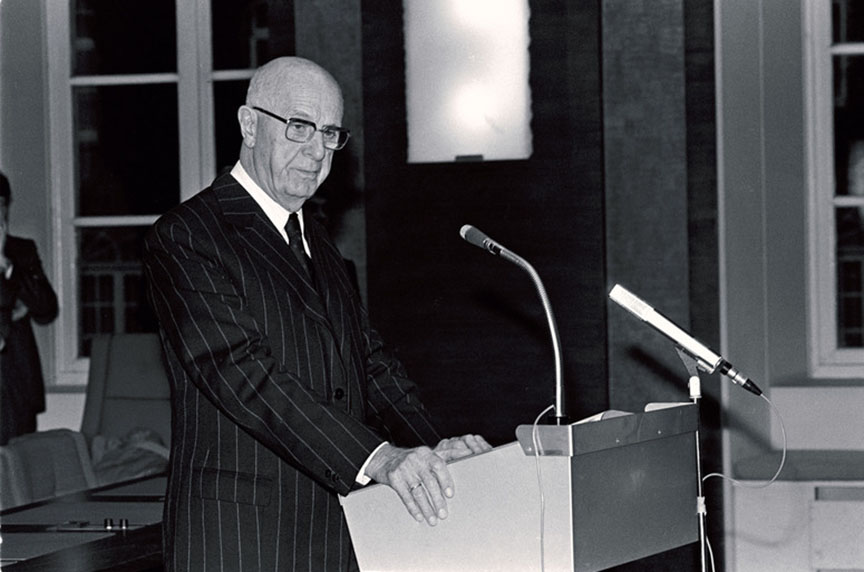

Last December, NATO commemorated the 50th anniversary of the “Report of the Council on the Future Tasks of the Alliance,” more commonly known as the Harmel Report. Initiated by Pierre Harmel, the former Belgian minister of foreign affairs, the report not only averted permanent damage to the Alliance that could have resulted from policy disagreements among Allies, but also directly led to the launch of a number of initiatives to stop the arms race and ease East-West tensions. Unfortunately, much of the significance of this document has faded into history. Therefore, it is worth retelling the origins of the Harmel Report and to remember how it laid the foundations of the transatlantic security framework that exists to the present day.

Last December, NATO commemorated the 50th anniversary of the “Report of the Council on the Future Tasks of the Alliance,” more commonly known as the Harmel Report. Initiated by Pierre Harmel, the former Belgian minister of foreign affairs, the report not only averted permanent damage to the Alliance that could have resulted from policy disagreements among Allies, but also directly led to the launch of a number of initiatives to stop the arms race and ease East-West tensions. Unfortunately, much of the significance of this document has faded into history. Therefore, it is worth retelling the origins of the Harmel Report and to remember how it laid the foundations of the transatlantic security framework that exists to the present day.

By the mid-1960s, NATO stood in the most perilous state since its inception. The Alliance’s fragility was caused by a medley of interrelated factors. The Suez Crisis of 1956 and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 highlighted the lack of Allied political consultation. Following Joseph Stalin’s death, Allied views on a détente with the East also differed, adding additional pressures on the debate on NATO’s future military strategy vis-à-vis the Warsaw Pact. Confidence in NATO’s military might waned further in 1957 with the Soviet launch of Sputnik, implying a dangerous East-West gap in technology. Yet these issues paled in comparison to France’s ground-breaking 1966 decision to leave NATO’s military command, which ominously coincided with the potential expiration date of the NATO Treaty in 1969.

In light of this daunting list of developments, Harmel sought to arrest the negative trends and to revitalize the Alliance. On December 16, 1966, he initiated a landmark study, commissioned by the Allies, to analyze the events of the past twenty years and their effects upon NATO. The goal was to determine the future tasks of the Alliance and to ensure its survival beyond 1969. One year later, the Harmel Report was adopted. The barely seventeen-paragraph-long analysis touched every aspect of NATO’s organization, function, and strategic direction, but it was only the tip of the iceberg. During the writing process hundreds of documents were produced that discussed issues such as East-West relations, general defense policy, and the balance between the military and political roles of NATO, to name a few.

The report managed not only to save the Alliance from a crisis of substance, but by highlighting two main functions for NATO, gave it a bold new vision on how to move forward.

According to the report, NATO’s first function was to “maintain adequate military strength and political solidarity to deter aggression and other forms of pressure and to defend the territory of member countries.” The second was to “pursue the search for progress towards a more stable relationship in which the underlying political issues can be solved.”

These two functions of military security and détente provided the conceptual framework to address the future of the Alliance. The rationale was that once Allies felt completely secure from external threats, and within the context of improved NATO consultation, they could more confidently play a leading role in resolving the political conflicts of the day and hastening the end of the East-West arms race.

And so they did.

NATO’s adoption of the conclusions of the report led directly and almost immediately to the launch of initiatives on three fronts to stop the arms race and ease East-West tensions.

First, it fired the starting gun for what would eventually become the Mutual Balanced Force Reduction (MBFR) talks. Four weeks after the approval of the report, Allies began work on various sets of disarmament models. Their preparations culminated at the June 1968 NATO Foreign Ministerial, with the call to the Warsaw Pact countries to start disarmament talks. While the drawn-out MBFR negotiations failed to produce a treaty, in 1990 their findings were used to form the basis of the Conventional Arms in Europe Treaty (CFE). By greatly improving military transparency, capping the ceiling of heavy military equipment such as tanks and aircraft, and reducing the risk of war, the CFE Treaty became one of the cornerstones of arms control, confidence-building, and security in Europe.

Second, the report provided NATO with the institutional mandate for an East-West détente. Initially progress was slow, and the Warsaw Pact’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 did not help the cause either. But, by the turn of the decade, NATO and the Warsaw Pact readied for Multilateral Preparatory Talks. Within a number of years these talks led to the Helsinki Final Act of 1975—a code of international conduct based on mutually agreed rules to which all signatories would adhere. It also established the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE), which would eventually become the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) of today.

Third, it strengthened Allied consultation on all matters in the US-Soviet relationship that affected European security. Allies were actively involved in the bilateral US-Soviet negotiations on the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and in the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT). Later on, the United States turned to the Allies once again for advice and input on the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) talks with the Soviets. The INF Treaty in particular became one of the most successful arms control treaties of all time as it both eliminated an entire category of nuclear weapons and reduced the likelihood of a surprise nuclear strike.

Granted, this is not to suggest that the Harmel Report was the only, or in all cases, the dominant factor that led to this flurry of activities. There were other great forces at play such as the West German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik and US President Richard Nixon’s pursuit of détente, to name but a few. But it was the Harmel Report that became the connective tissue, facilitating Western efforts to resolve these major issues and established NATO as the hub for coordinating all three of these work strands.

In sum, the Harmel Report is one of NATO’s landmark achievements and possibly one of the most underrated documents of the Cold War period. Not only it did establish NATO’s dual-track policy of deterrence and détente, but it led also to NATO’s launch of initiatives which provided the foundation of the modern transatlantic security landscape. For these reasons, the Harmel Report needs to be recognized and understood by today’s generation of leaders not only as one of NATO’s finest hours of the past, but also as a valuable source of guidance for the challenges that NATO faces today.

Jamie Shea is NATO’s deputy assistant secretary general for emerging security challenges. This article is the personal opinion of the author and does not reflect an official view of NATO.

Image: Pierre Harmel, a former Belgian foreign minister, initiated the 1967 "Report of the Council on the Future Tasks of the Alliance" at a time when the existence of the Alliance was put into question. The report came to be known as the Harmel Report. (Photo courtesy of NATO)