Finance Ministers and central bankers will gather in Washington from April 15-17 for the spring meetings of the Bretton Woods Institutions: the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. It will be an important opportunity to check in on the global economy. Here are five key topics to pay attention to during the meetings.

Finance Ministers and central bankers will gather in Washington from April 15-17 for the spring meetings of the Bretton Woods Institutions: the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. It will be an important opportunity to check in on the global economy. Here are five key topics to pay attention to during the meetings.

1. Global debt

In 2015, global public debt stabilized but remained far above pre-crisis levels. This trend is not only observable in the euro area, where public debt grew the most, but worldwide as well. Public debt as a share of GDP has risen because of protracted economic slowdown in most parts of the world and expansionary fiscal policy aimed at counterbalancing weak demand. With this high level of public debt, it is imperative that markets retain confidence in the capacity of large issuers—such as the United States, Japan, Italy, France, and Germany—to roll over their public debt. Things seem to have gone smoothly over the past two years as new debt has been issued at very low interest rates, and even at negative rates countries. However, it is still possible that markets will abruptly change their view and start demanding higher-risk premiums if mounting lack of confidence or misplaced policy come about. To uphold confidence, it is crucial that countries continue pursuing prudent fiscal policies and maintain a balance between stimulating the economy and ensuring financial markets that debt will be rollover at low and stable interest rates.

Furthermore, private debt is also high. While certain advanced economies have seen some deleveraging in recent years, in most countries private debt continues to stay well above the level of public debt. In some emerging markets, the situation has become dangerous as the level of corporate debt rose substantially during and after the great recession: between 2007 and 2014, corporate debt grew by twenty-five percent of GDP in China, by roughly twenty-three percent of GDP in Turkey, and by fifteen percent of GDP in Brazil.

Global debt will likely continue to grow for a number of factors. First, in a low-interest-rate environment, lending is cheap for both the government and corporate sectors. Second, several advanced economies are engaging in expansionary fiscal policies to support internal demand given low levels of private activity. Third, low inflation does not help bring down the debt-to-GDP ratios. Question No. 1: Will excessive debt put the brakes on global growth?

2. Sub-emerging economies

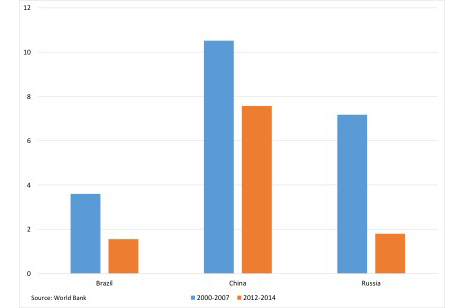

In the past fifteen years, the world has increasingly talked about emerging economies, referring to a group of countries with significantly higher-than-average growth rates that were rapidly catching up, developmentally, with the so-called advanced economies. However, in the past few months it has become evident that these countries may no longer be emerging, and not because they have caught up with the more advanced economies. Instead, they have simply not been able to generate the same level of growth as in the past. This is because of a variety of reasons: political instability and weak institutions in Brazil, economic sanctions and low commodity prices in Russia, and low internal demand in China etc. (Graph 1). Question No. 2: Will Brazil be the IMF’s next client? Or, as in House of Cards, will the IMF prepare a rescue package for Russia?

Graph 1 – Average annual real growth rates

3. Oil producers

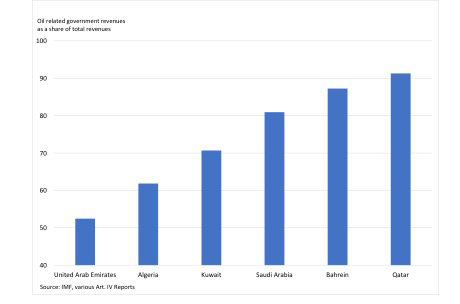

Low oil prices have had severe impacts on economies that are heavily reliant on oil revenues. All of the most significant Arab Gulf countries rely on oil for more than fifty percent of government revenue. Bahrain, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia rely on oil for more than eighty percent of revenue. According to major forecasters, oil prices will remain low for the foreseeable future.

For oil-dependent economies, adjusting to the new reality of lower oil prices will not be easy because of reduced government revenues, which will affect some of the fundamental aspects of citizens’ lives through increases in income tax rates and reduction of fuel subsidies. Although, in general, these countries’ large sovereign wealth funds reserves have allowed them to cope with the oil price decline—and will continue to do so in the short term—they may experience turbulence if they adjust domestic policies with the goal of making public finances more sustainable in the medium term. Question No. 3: Will Arab Gulf countries successfully adjust to the new reality of low oil prices in the long term?

Graph 2 – Public revenues from oil production

4. World liquidity

In response to the global financial crisis, central banks created liquidity to allow for improved functioning of the interbank market. Even as inflation reached its lowest band, central banks have continued to increase the size of their balance sheets. As of now, total assets of the world’s major central banks (the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, and the Bank of Japan) are $16.3 trillion, $10 trillion greater than before the financial crisis. Although this contributes to maintaining low interest rates that are designed to stimulate the real economy, it can also lead investors to take higher risks in search of yields, and families to make risky investment decisions. Despite all the macro prudential tools that are now in place, the risk of a bubble on the markets the bursting of which could abruptly affect the recovery cannot be ruled out. Question No. 4: Are central banks policies contributing to a new bubble?

5. Low inflation

Central banks have to ensure price stability, which is often defined with a target inflation. For major central banks, this target is generally around two percent. However, the current inflation level is far from the target. Latest figures show an inflation of one percent in the United States, -0.2 in the euro area, 0.3 in the United Kingdom and Japan.

Low inflation rates raise several questions about the availability of fiscal and monetary tools in the current environment, especially after the massive injection of liquidity by most central banks over the past few years. Low inflation rates are an indicator of a depressed global economy. They can lead to expectations of even lower inflation, resulting in consumers and investors postponing buying. This may affect global recovery. Moreover, the effort to reduce debt— public as well as private—becomes more painful because the real value of debt remains stable. The result is less public resources for productive expenditure, high taxes, and less private investment. Question No. 5: Quantitative Easing to infinity?

Global economic stability is not yet at pre-crisis levels. As a result of rising geopolitical tensions, there is a greater need for a more coordinated approach by key global economic players to avoid unnecessary stress. Intelligent use of public budgets, and coordination on commodity prices, global economic governance, and monetary policy can all contribute to a more stable economic future.

Andrea Montanino is the Director of the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics program and a former Executive Director of the International Monetary Fund.

Image: International Monetary Fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde and World Bank President Jim Yong Kim participate in an IMF-World Bank discussion on climate change at the 2015 Annual Meetings of the IMF and the World Bank in Lima, Peru, on October 7, 2015. Finance Ministers and central bankers will gather in Washington from April 15-17 for the spring meetings of the IMF and the World Bank. (Reuters/Mariana Bazo)