Volodymyr Ruban Crosses the War’s Front Lines to Negotiate With Russian-Backed Separatists

Amid the war in southeast Ukraine, hundreds or thousands of people have been imprisoned by both sides – some as enemy combatants, others more arbitrarily. The man whom both sides call to get hostages or prisoners released is an officer of Ukraine’s military reserves, Colonel-General Volodymyr Ruban. Working nearly alone and unarmed, Ruban since May has negotiated the release of more than 200 military and civilian hostages.

Ruban criss-crosses the front lines of the war with only his son, a former officer of the state security service, the SBU, to drive him. “He doesn’t ask unnecessary questions, he’s a calm, well-trained guy and an excellent driver,” said Ruban in a recent newspaper interview. “By the way, that’s very important when you’re driving on mined roads or under fire.”

The Russian-backed separatist militias have abducted unknown numbers of people and were estimated to be holding at least 468 captives as of August 17, according to the United Nations’ latest monthly report on casualties and human rights violations in the war. Ukrainian human rights groups have described abductions as well by pro-government volunteer battalions, the UN report said, and Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council said August 3 the government had detained more than 1,000 people in the southeast for “terrorist activities.” Russia’s deployment of its regular army units into Ukraine – reported in recent days by Ukraine’s government, NATO and independent Russian and Western media – has led to the entrapment of a Ukrainian force near the town of Ilovaysk, where Ruban says 680 Ukrainian troops were taken prisoner.

In a conflict marked by deep distrust between Ukrainian officials on one hand, and Russia’s government and proxy forces on the other, Ruban has become the war’s most prominent hostage negotiator by proving himself the man whom both sides can trust. He has done so largely by trading on the honor and mutual respect of senior officers on both sides who once trained, served and even went to war together in the same Soviet military.

Ruban, a solemn-looking former air force pilot with a shaved head and trimmed, graying beard, fell into his role because he headed Ukraine’s Ofitserskiy Korpus, (“Officers’ Corps”) a veterans’ organization. In May, a member of group – a retired police officer who had supported the Ukrainian pro-democracy Maidan movement, which Russia opposes – was one of several people taken hostage by armed separatists. Knowing that the officer and four other hostages had been wounded while fighting their attackers, Ruban quickly negotiated their release in exchange for three government detainees whom their captors wanted freed. Ruban personally delivered the wounded men to hospitals.

After this exchange, family members and friends of hostage began approaching Ruban for help. As he built his contacts with the separatists, he has sometimes freed a hostage with a single phone call. His Ofitserskiy Korpus has established a Center for the Release of Prisoners, which maintains a database of captives and missing persons.

One of the people Ruban helped release is Vasyl Budik, a former Soviet army officer who spent more than ninety days as a hostage before Ruban arranged his exchange, with fourteen other Ukrainian military and security officers, for a Russian woman named Olga Kulygina, whom Ukrainian authorities arrested when she entered Ukraine with more than $20,000 in cash intended for the separatist war.

Budik was held by former Russian army Lieutenant Colonel Igor Bezler, one of the rebels’ most prominent commanders, who conducted a mock execution of Budik and has been accused of other abuses. While Bezler became known for brutality, Ruban says the rebel leader valued the word of a fellow officer and always kept his own word. Bezler operated by certain rules, which he was fond of repeating, Ruban said. A person with a gun is an enemy, if he drops his weapon he is a prisoner, and all wounded are given aid. Bezler, who cultivated the nom de guerre “Demon,” fled a Ukrainian advance on his stronghold in July and has not been seen since. “I hope Bezler still abides by those rules,” Ruban told the weekly newspaper Dzerkalo Tyzhnia.

The common Soviet army background of Russian and Ukrainian officers older than forty facilitates Ruban’s negotiations, according to Budik. “Once we were all in the same army, we served in Afghanistan,” he said. “And thanks to those connections, we can come to an agreement about the release of hostages.”

Since his release, Budik has been advising Ukraine’s Defense Ministry on hostage and prisoner issues, working with Ruban. “He has a trusted reputation, he’s helped return our wounded and dead, he’s kept his word and delivered on his promises” said Budik by telephone from Kyiv. “He considers each word that he utters very carefully, he is very reserved, there is nothing flippant in what he says. He does not allow himself the smallest mistake, because even the smallest mistake could cost a life,” said Budik.

Hostage negotiations in this dirty war do not take place in gilded state rooms or comfortable hotel suites. Ruban drives into separatist-held territory to meet his interlocutors over a cup of tea in the cafeteria of a seized regional administration building, in the room where the hostages are held, but most often eye-to-eye in the office of the rebel leader, whether it is Bezler or the newly designated prime minister of the “Donetsk People’s Republic,” Oleksander Zakharchenko.

While the rebel forces include many former officers who abide by a military code of honor, they also include “bandits” Ruban says, over whom the self-proclaimed Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics have little control.

“I learned how to work quickly, not using mercenaries but our well-trained officers,” Ruban told Dzerkalo Tyzhnia. “The opposing side prefers to work with those who don’t represent the government. They trust me. I learned to look for honorable solutions in difficult situations. We are not trading people, we are coming to an agreement,” he said.

Irena Chalupa covers Ukraine and Eastern Europe for the Atlantic Council.

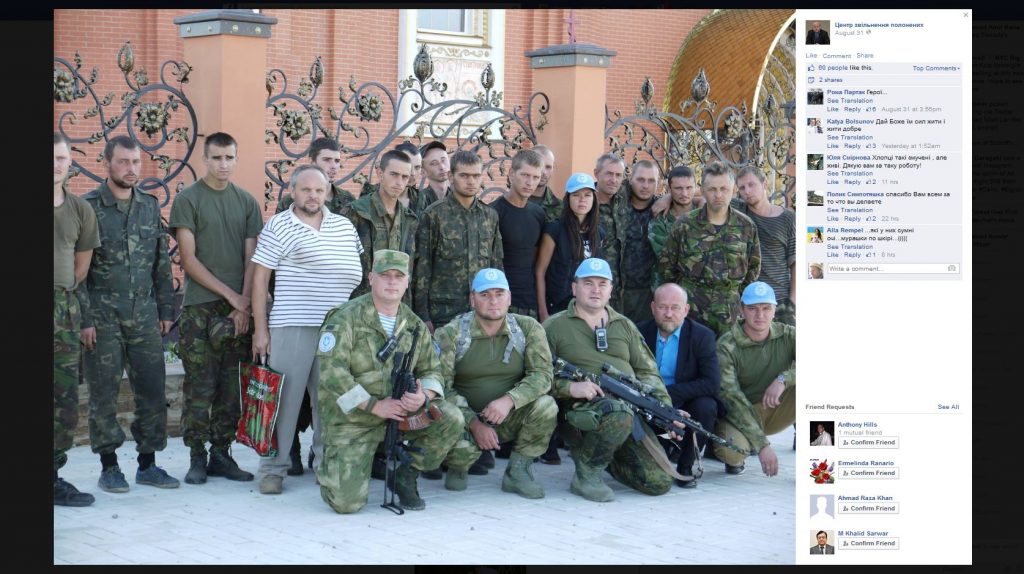

Image: In a photo on the Facebook page of his Center for the Release of Prisoners, Volodymyr Ruban, in his customary dark suit at right, poses with members of his organization and 16 Ukrainian troops whose release he negotiated, along with Ukrainian musician Ruslana Lyzhychko, center. (Facebook/Center for the Release of Prisoners)