Latin America is poised to take on a lead role on climate change and renewable energy in the global arena in 2017. The enormous potential and rapid spread of renewable energy in the region has fueled hope of a global transition to a low-carbon economy. The added bonus: an economic opportunity that extends well beyond the borders of Latin America.

Latin America is poised to take on a lead role on climate change and renewable energy in the global arena in 2017. The enormous potential and rapid spread of renewable energy in the region has fueled hope of a global transition to a low-carbon economy. The added bonus: an economic opportunity that extends well beyond the borders of Latin America.

Technological innovations have increased efficiency and reduced costs boosting the grid competitiveness of renewable energy. According to a World Economic Forum report in December 2016, in countries around the world—notably Brazil, Chile, and Mexico in Latin America—solar and wind energy are outcompeting fossil fuels. Bloomberg New Energy Finance predicts solar energy may be cheaper than coal globally by 2025, or earlier in places that have limited coal deposits and a carbon tax, such as Brazil. Following the revolutionary shift in 2015, when renewables surpassed coal as the world’s largest source of installed power capacity, new wind and solar installations set records in 2016.

According to the latest International Energy Agency report, as demand grows over the next five years, renewables will remain the fastest-growing source of electricity. The benefits are significant—renewables are becoming the practical first-choice option for new energy generation.

With 53 percent of generation capacity from renewables, Latin America is already leading the global green energy movement. In 2016, Costa Rica ran purely on renewable power for months at a time, and Uruguay generated 92.8 percent of its electricity from renewables.

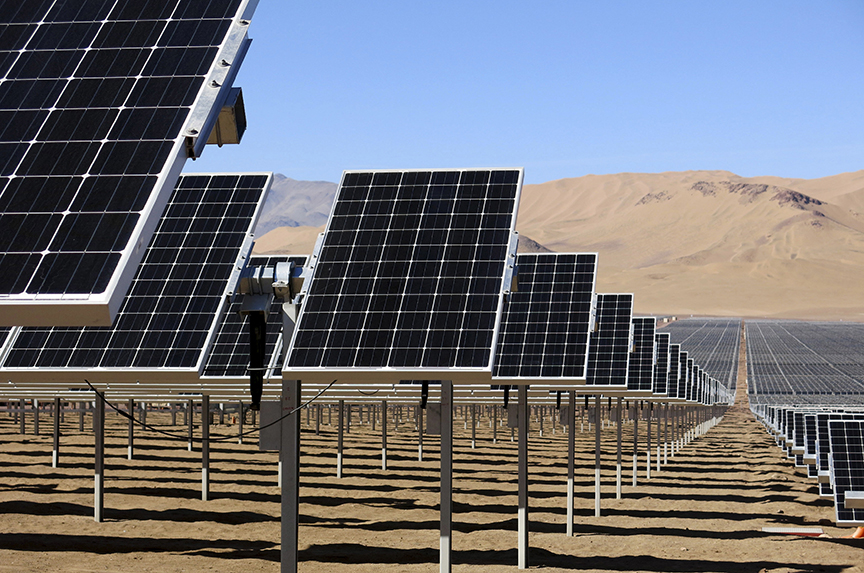

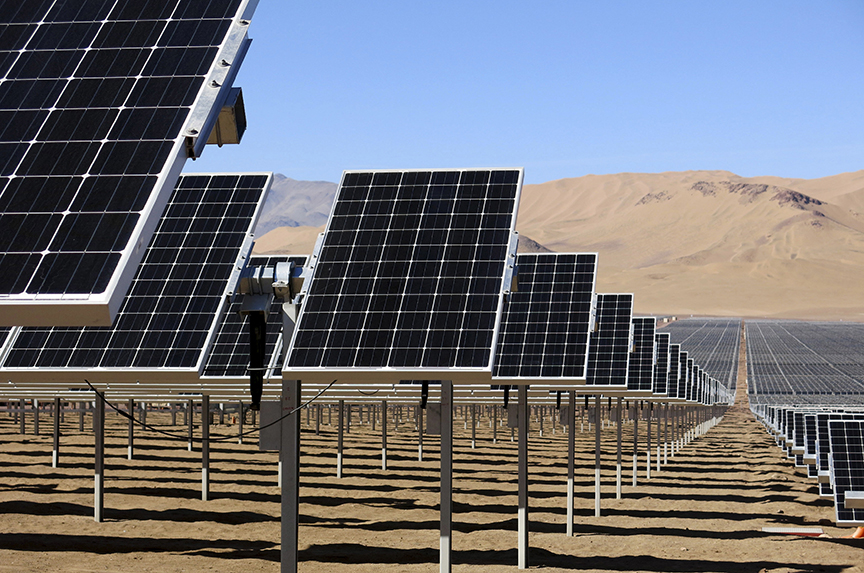

This year opened with good news for renewable energy. Argentina’s president, Mauricio Macri, issued a decree to significantly develop his country’s renewables sector within the year. And, Google Chile announced it now gets 100 percent of its electricity from renewable energy—776,000 solar panels installed across the Atacama Desert. In addition to supplying Google’s data center and offices, the El Romero solar plant—one of the largest photovoltaic projects in the world—will produce enough clean energy to power 250,000 homes while avoiding around 475,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions from existing coal-fired plants.

The Chilean solar plant is emblematic of the region’s vast renewable energy potential, and the combination of national policies and innovative finance mechanisms that are driving renewable energy investments and development. An increasing number of countries are using energy auctions to award capacity to renewable energy developers at low prices; recent power auctions in Argentine, Chile, Mexico, and Peru resulted in high participation and record-low bids for wind and solar projects.

Brazil, Chile, and Mexico—followed closely by Argentina—ranked among the top ten of Ernst & Young’s renewable energy country attractiveness index (RECAI). The ranking features the countries’ ambitious clean energy targets, fiscal incentives, and legislations such as Mexico’s energy transition law, which is designed to create a favorable business climate and boost investor confidence in the long-term market for renewables (You can read more about Mexico’s progress here.). Additionally, in December, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico issued inaugural green bonds to further green investment, as reported by Climate Bonds Initiative.

In many countries in Latin America, most notably Brazil, auctions and infrastructure projects now come with greater opportunities for foreign investment. Many have no requirements for minimum local content for developers. As home to some of the most promising, untapped markets for renewable energy, Latin America is ripe for investment.

In addition to the focus on renewables, there is a growing awareness about land use and a sense of urgency about forest protection and conservation in Latin America.

At the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP13) in Cancún, Mexico, in December 2016, Brazil’s ministries of agriculture and the environment pledged to jointly restore and promote sustainable agriculture across 22 million hectares of degraded land. The announcement represented the largest restoration commitment ever made by a single nation. This effort will absorb significant amounts of greenhouse gas emissions while promoting agricultural productivity along with biodiversity and water management.

Other headlines to be celebrated from last fall include the agreement between Colombia, Costa Rica, and Ecuador to protect the most biodiverse ocean corridors near the Galápagos Islands and Colombia’s plan to integrate forest protection, including the recognition of indigenous land rights, with its peace process with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebels.

Why all this activity in the Americas? It is because the stakes are so high. The severe impact of climate change is visible across the region. In a 2015 Pew Research Center survey, 77 percent of Latin Americans—the highest in the world—reported being concerned about the immediacy of climate change. Moreover, although Latin America only accounts for 12.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to the World Bank, if the Earth’s temperature rises more than 2°C, Latin America will be one of the regions most affected.

In preparing the recent Latin America 2030: Future Scenarios report, the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center asked six Central American ambassadors what they believe will be the principal issue affecting the isthmus in ten years. All of them said climate change. The report suggests that, if current trends continue, the melting of glaciers in the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes will accelerate to the point where most glaciers below 5,000 meters will disappear entirely—disrupting water supplies and affecting millions of people dependent on agriculture and hydroelectricity. Economic loss, destruction, and displacement caused by intensified storms, flooding, and droughts are already taking place and will only continue as temperatures and sea levels rise.

Latin American leaders have joined other global leaders to reaffirm their commitment to the Paris climate agreement. As in many other areas, the continent’s commitment to clean energy and climate change is increasingly an example to be followed.

Mae Louise Flato is a former project assistant at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

Image: Solar panels are seen in the Atacama Desert in Chile in this June 5, 2014, file photo. (Reuters/Fabian Andres Cambero)