Angela Merkel has acknowledged that the setback her party suffered in elections in an eastern state this past weekend was a repudiation of her welcome to Syrian migrants, but the Atlantic Council’s Fran Burwell said backing away from this controversial policy will only hurt the German chancellor further.

Angela Merkel has acknowledged that the setback her party suffered in elections in an eastern state this past weekend was a repudiation of her welcome to Syrian migrants, but the Atlantic Council’s Fran Burwell said backing away from this controversial policy will only hurt the German chancellor further.

“The voters would be more skeptical of her if she were to reverse what is a deep personal commitment, even though they may disagree with it,” said Burwell, vice president, European Union and Special Initiatives, at the Atlantic Council.

Merkel’s ruling Christian Democratic Union (CDU) suffered a humiliating defeat in elections in the northeastern state of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania on September 4, not least because this is the German chancellor’s home turf.

The CDU placed third with nineteen percent of the vote; the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany (AfD) placed second with twenty-one percent; and the center-left Social Democrats placed first with almost thirty-one percent. This is the first time that the CDU and its coalition partner, the Christian Social Union (CSU), have been defeated in elections in post-war Germany.

“In some ways, what we are seeing is anti-globalization linked with incomplete revolutions from 1989,” said Burwell. “The question is can Europe resolve these together—which I think, really, is its only choice—or not?”

The vote is seen as a referendum on Merkel’s migrant policy. Over the past year, Germany has taken in around one million refugees—mostly people fleeing conflicts in the Middle East in general, and Syria, in particular.

Merkel’s initial response to the election results has been to dig in her heels on her migrant policy. Elections will be held in Berlin in two weeks, and in three other states in 2017 before national elections in the fall.

Merkel has not said whether she would seek a fourth term. While under pressure to roll up the red carpet that she laid out for the migrants, she does not face any serious challenger from within her ruling bloc.

The election results show that all parties should be worried by the rise of the AfD, which attracted voters from each party. AfD’s strong performance is, indeed, reflective of the rise of the political fortunes of the far-right across much of Europe. Nevertheless, the AfD has little chance of being part of a ruling coalition in 2017.

“This election is likely to mobilize the others against the AfD,” said Burwell.

Fran Burwell spoke in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts from our interview.

Q: What does the Mecklenburg-West Pomerania election outcome mean for Chancellor Merkel’s political future and that of her Christian Democrats?

Burwell: It is a setback, but I would not call it a disaster. It is indicative of the problems we are seeing right now both in Europe and the United States.

There are a lot of peculiarities about Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. It is an eastern länder (state)—in what was formerly East Germany. It is not a wealthy area; its population is considerably smaller than some of the big länders in the west. Its population is older and not diverse. You have this phenomenon that you are seeing both in Europe and the United States where you have older white voters rejecting change in society.

It is a setback in that it is Chancellor Merkel’s constituency, so it proves that she doesn’t have coattails in the sense that an American politician might have in their local district. It will encourage AfD elsewhere in Germany, but it will also wake up the other parties to realize this—the concerns of citizens who are upset about the economy—is something they have to address. Although Germany is doing very well economically, there is a feeling in certain parts of the country that they are not benefitting from a healthy economy.

Q: Is it then too early to write Merkel off?

Burwell: Oh, yes. She is a survivor. First, there is no obvious successor in the CDU. Second, she remains more popular than her party. The general election will be held a year from now. That is a very long time in politics. It is expected that she will announce that she is running again sometime in the next couple of months.

Q: Chancellor Merkel has said she is sticking by her controversial immigration policy. Is changing course, however, the only way to improve her party’s prospects?

Burwell: I don’t think so because she is a politician who is known to be conservative with a little c. Her governance is based on consensus of the coalition. She finds out what everyone else wants before proceeding.

There have been two exceptions, however. One was the rapid reversal on nuclear power plants after the Fukushima [nuclear plant] disaster. The other was the refugee crisis. She has several times said that she once was on the other side of the wall looking in. These two things—a real personal commitment—is something that we have not seen too many times from her. The voters would be more skeptical of her if she were to reverse what is a deep personal commitment, even though they may disagree with it.

Q: What do Merkel’s political misfortunes and the rise of the far-right mean for Europe at a time when the Continent is dealing with serious challenges such as Britain leaving and migrants arriving, and has economies that are limping back from a crippling recession?

Burwell: It makes clear the divisions in European society between those who see things as going well and those who feel that they are excluded from the progress.

For example, there is a huge turnaround in the Irish economy, but it is not clear that it is felt by all the Irish. The same has been happening in many other economies.

We also have a lot of political rhetoric that is nationalist in tone. The refugee crisis has been a huge strain on Europe’s body politic and the consensus within Europe. In a way, the election in Germany narrows the split between Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and the countries of Western Europe. The part of Germany that voted for the AfD is in the east. It is former Warsaw Pact. In some ways, what we are seeing is anti-globalization linked with incomplete revolutions from 1989. The question is can Europe resolve these together—which I think, really, is its only choice—or not?

It has been a different debate on the Continent than it has been in the United Kingdom, so I don’t expect anyone to leave the EU other than the British. But for a healthy EU you need to have more countries moving forward together with their publics and it is clear that that’s a real challenge right now.

Q: What is the likelihood that the AfD will be part of a ruling coalition in Germany in 2017?

Burwell: Not in the short term. This election is likely to mobilize the others against the AfD. Just like in our system, these länder elections that are held outside the national election become a protest vote. It is also interesting that the AfD took voters from all other parties, so they all have an interest in fighting the AfD.

Q: What are the broader implications of the German vote for upcoming elections in other countries in Europe?

Burwell: It puts more of a spotlight on the French vote. I am actually less concerned about the German presidential vote next year because you do have a strong incumbent in the shape of Chancellor Merkel. This particular länder [Mecklenberg-West Pomerania] is an outlier. But in France you do have the rising popularity of the National Front and you have a very weak political leadership. You have a very weak president. All the alternatives that are coming up to President [François] Hollande are also weak or have been tried—like [former President Nicolas] Sarkozy has been tried in the past. There is not an obvious candidate where everyone is going: “This is the right person to put up against [National Front leader] Marine Le Pen.”

Q: Who benefits from such a situation?

Burwell: I don’t think anyone benefits except perhaps [Russian President Vladimir] Putin. I don’t think the people of Mecklenberg-West Pomerania will get more jobs because of this vote. The AfD does not bring that kind of policy sophistication. It is not as though this is going to change any of the existing policies. It will be good for the more establishment parties to look at why there is so much anti-establishment feeling across Europe. They are starting to do that, but this is a long process, just as it is [in the United States].

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications at the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.

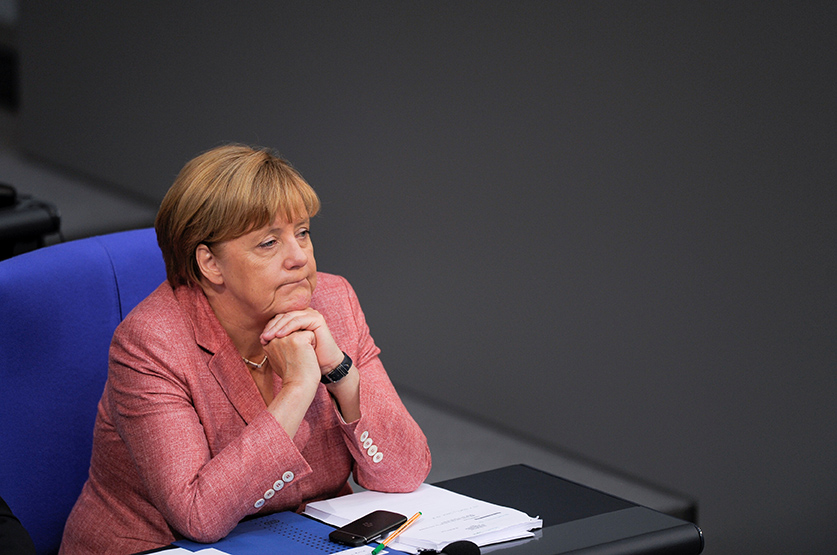

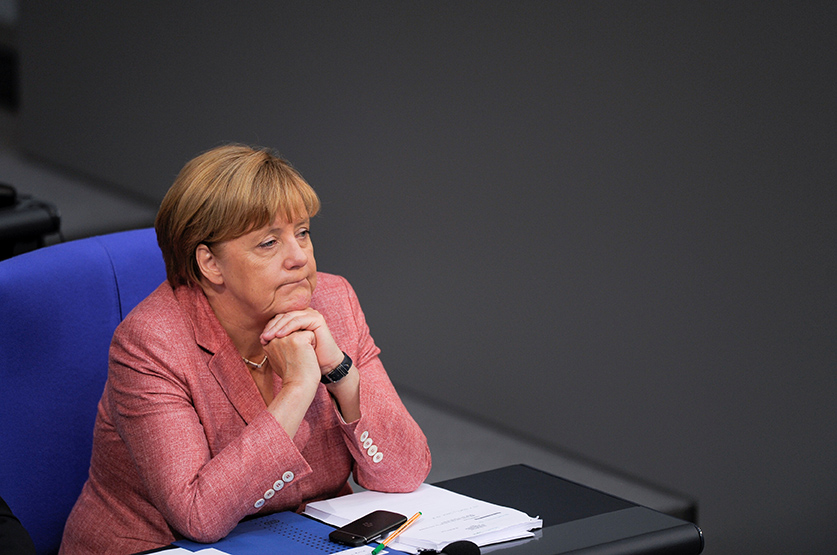

Image: German Chancellor Angela Merkel attended a meeting of the lower house of parliament in Berlin on September 6. (Reuters/Stefanie Loos)