In an age in which economists and policy makers are openly advocating for advanced economies to stop worrying about budget deficits, Japan usually features as the poster child for the seemingly never-ending story of printing money to fund government spending. While some question when the music eventually stops, others tout Japan as the example par excellence of this “Modern Monetary Theory,” and a model to be followed for cash-strapped, debt-laden, and rapidly aging societies.

Looking beyond the debates about monetary policy, however, and digging into the real economy, Japan has adopted other practices that might be emulated as policy makers, companies, and investors pursue economic growth and profits in an era of secular stagnation. As it enters its new “beautiful harmony” Reiwa Era of Emperor Naruhito, commands the helm of the Group of Twenty (G20), and prepares for the 2020 Olympics, Japan merits a closer look for its employments policies, its pragmatic and non-traditional geopolitical position, and its embrace of a forward-thinking and profit-minded stance in infrastructure development and investment.

Whither elders, women, and immigrants?

As we survey the Japanese economic landscape, several headwinds lurk on the horizon. In terms of external shocks, the ongoing uncertainty of the US-China trade conflict has had significant downside impact on Japan. While China acts as an aggregator of regional trade surpluses—often taking inputs from countries such as Japan and South Korea, adding value, and then exporting the final—the decrease of exports from China and across Asia has had negative impact on Japan. With weaker demand from China, corporate profits in Japan have slipped and exports have fallen. And, as we can see in Figure One, wage growth in Japan has turned negative since the start of 2019.

Figure One: Wage growth in Japan

source: tradingeconomics.com

Retail sales have also remained relatively flat, perhaps contributing to Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s decision to once again delay an increase in consumption tax from 8 to 10%. (Although the recent results of the House of Councillors election may mean the consumption tax increase comes into effect in October). Crucially, a recent Cabinet Office report specifically referred to “worsening” economic conditions in Japan, despite a modest uptick in manufacturing activity.

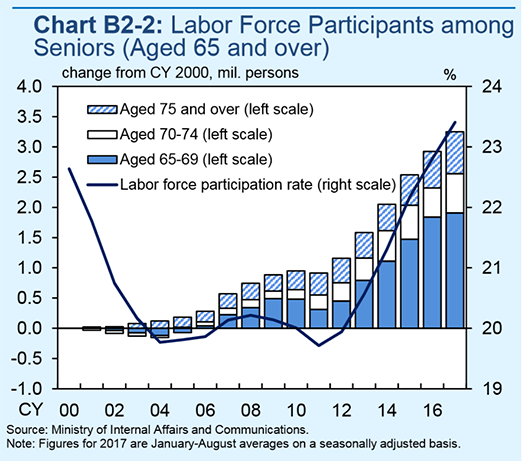

However, beneath the doom and gloom, the current government has put into motion several key policies that have changed economic behavior in Japan—part of the prime minister’s “Abenomics”—and might prove to be alluring examples for other countries. In terms of demographics, Japan is often portrayed as a rapidly aging society, portrayed by its ranking as #2 on the global “median age” leaderboard. A seminal move in Abenomics has been to increase the labor force participation (LFP) rate of over-sixty-five-year-old workers. As illustrated in Figure Two, policy changes—such as promoting the active recruitment of retirees—have had a quantifiable impact on LFP for seniors.

Figure Two: Japan, labor force participation rate, over-sixty-five-year-old workers

Source: https://www.boj.or.jp/en/mopo/outlook/box/data/1710BOX2a.pdf

And in terms of “womenomics,” Abe’s policies of increasing paid family leave have had a dramatic increase on LFP for women in Japan. As indicated in Figure Three, female LFP has shot up in Japan in recent years, off the back of common-sense policies to utilize significant underlying potential in a country’s economy.

Figure Three: Japan labor force participation rate, female (percent of female population above fifteen-years-old (modeled International Labour Organization estimate)

While Abe’s policy to encourage companies to increase the number of women they have on boards is laudable. Removing or alleviating the cost of childcare was a significant step change—certainly one that is applicable to increasing LFP for women in the United States, where the cost of childcare often remains prohibitively expensive.

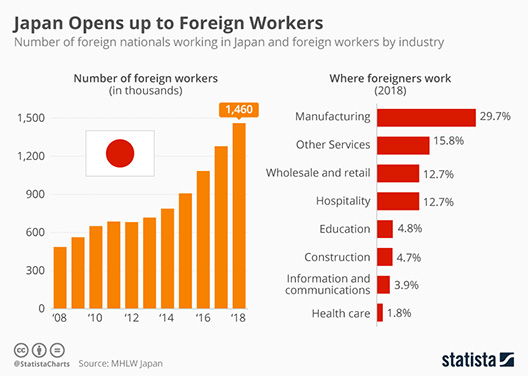

In addition, while much of the world is mired in debates about immigration, traditionally inward-looking Japan is opening up its labor force to foreign workers. As we can see in Figure Four, the number of foreign workers has shot up, nearly doubling within the last five years.

Figure Four: Number of foreign workers in Japan (thousands) and sectors

Source: https://www.statista.com/chart/16838/number-of-foreign-workers-in-japan/

As learning Japanese can be a challenging task, a number of companies are equipping new immigrants with high-tech services designed to ease the assimilation process. Additionally, looking beyond the megalopolis of Tokyo, the government is implementing policies to address labor shortages in rural areas and within specific sectors such as construction, hospitality, and healthcare. Such targeted initiatives may also be helpful for other advanced economies concerned with addressing both present and future labor shortages.

Pursuing connectivity and stability

In looking to Japan’s role in the wider Asia-Pacific region, the perceived withdrawal of the United States from the region symbolized by Washington’s departure from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, the ongoing US-China trade war, and recent mutterings about ending the Japan-US security treaty have contributed to Japan’s geopolitical uncertainty. Amidst this power vacuum, it can be argued that Japan’s preference (and history) of pursuing and promoting a pragmatic economic diplomacy, combined with non-traditional security aims—such as overseas development assistance (ODA), regional interconnectivity, and shuttle diplomacy underpinned by long-term investing opportunities—are commendable examples for countries seeking to maintain relevance and prosperity in a low-growth world.

Japan’s evolving relationship with China is a case in point. Despite talk of initiatives such as the “quad” security arrangement—involving Japan, Australia, India, and the United States as a counterbalance to China—it should be noted that historically, the notion of China as a security threat was “alien to the Japanese government,” according to Yoshihide Soeya. Indeed, during the Cold War (and until things shifted with US President Richard Nixon’s policy of “opening” China), Tokyo found the Washington prerogative of containing Beijing to be most concerning. For it was in Japan’s direct interest to maintain a stable, prosperous, and integrated mainland—even if this position was at odds with Washington’s anti-communist stance in the region. In recent years, relations between Japan and China have been mixed at best, beset with nationalistic language and mutual suspicions on the one hand, and proclamations of positive support on the other.

Two recent developments, however, have altered the geostrategic landscape and spurred an opportunity for deeper cooperation between the two great powers. The first – mentioned above – is America’s withdrawal from the Asia Pacific region, or the end of “Pax Americana.” And the second is the nuclear issue in the Korean peninsula. Indeed, no matter what kind of market-quelling declarations of peace are promulgated from the White House, the United States’ bellicose threats against its economic trading partners—and its decisive withdrawal from the TPP/CPTPP trade agreement (of which Japan is a member) ignify a clear disengagement from its trading partners in the region. These relationships also imbued a sense of security for countries looking to the United States for protection. In the wake of this power vacuum, the prospect of a harmonious relationship between Japan and China would be monumental—and centripetal for stability and prosperity in the region. With regard to North Korea, any meaningful resolution to the issue of nuclear proliferation is likely to involve the direct participation of Tokyo and Beijing, as well as Seoul (rather than a bifurcated discussion between Washington and Pyongyang).

With Abe’s visit to Beijing late last year—calling for a “new era” in relations between Japan and China—and a reciprocal state visit planned for Chinese President Xi Jinping in Tokyo next year, change is afoot. Significantly, this warming of relations is underpinned with tangible deals, as Japan and China have agreed to jointly invest in about fifty deals in third country infrastructure development, with a smart city in Thailand as a key initial project.

From Abe’s China summit diplomacy and its substantive foundation for infrastructure deals, one can discern a common theme in Japanese foreign policy: that of emphasizing connectivity and of acting as a stabilizing force in the region, whether through bilateral relationships or multilateral channels. These ties are often cemented with economic opportunities for Japan, as well imbued with rich trading relationships. Historically, Japan engaged with southeast Asia in resource diplomacy, providing ODA in exchange for commodities to fuel its own domestic industry. Now, while countries such as Vietnam have blossomed into their own manufacturing powerhouses, Japan acts as the country’s single largest foreign investor, seeding projects such as the Hanoi Metro, and drawing in other multilateral players and spurring business opportunities across sectors.

Prosperity for the home front

This kind of “pragmatic economic diplomacy“—with the potential to foster stability, stimulate local development, and advance profit-making opportunities—is an excellent example to follow for cash-strapped and insecure governments in the West. As the model of “Japan Outbound, Inc.” creates opportunities for the private sector in real economies abroad, it also has the potential to generate wealth back at home. Indeed, while concern over whether the government can afford their future pensions, Japanese millennials are currently increasing investments in domestic equities in order to create their own nest eggs. So in creating opportunities abroad through ODA and public-private partnerships, Japan may not only be contributing to the economic development of the host country, or exclusively securing profits or employment for Japanese companies, but also generating prosperity for young people on the home front.

For institutional investors—particularly those with a low risk mandate or limited exposure to Asia— tracking Japan’s outbound activity may yield significant opportunities for public-private partnerships in the infrastructure space. With the expansion of infrastructure mandates for some of Japan’s most conservative and largest institutions, the potential for co-investing is likely to expand. Additionally, while some financial actors and investors seem to be clutching at straws in their search for a clear codification of environmental, social, and governance standards and benchmarks for sustainable investing and business practice, Japan’s flurry of public-private partnership activity across Asia may yield opportunities for appropriate standard setting in the space of renewable energy, as well as smart infrastructure.

Conclusion

While much of the commentary on Japan focuses on topics of debt sustainability and quantitative easing, Tokyo has implemented several policies that have had a quantifiable impact on changing the domestic economic landscape. Rather than view Japan as a hopeless aging country, we would do well to follow their examples on fostering the participation of seniors and women in the workforce, as well as to strategically accommodating immigrant workers.

And as much of the world remains fixated on whether an eventual trade peace will be struck between the United States and China, Japan offers a common sense and pragmatic approach to engaging with other countries, backed up with profit potential. The multiplier effect that such interconnectivity has on infrastructure investing—and the associated opportunities for standard setting—is considerable.

Exploring the lessons of Japan, which are applicable to tackling the costs of Western societies’ aging demographics and in illustrating ways of injecting profit-laced dynamism and pragmatism in economic statecraft, may induce a bit of humility for those who harbor a fear-based view of China. After all, Japan—the country once vilified as the “land of the rising sun”—is now a guidepost for advanced economies. In turn, the target of the West’s current ire in the East may also provide lessons for now, and in decades to come.

Dr. Alexis Crow is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Global Business and Economics Program and leads the Geopolitical Investing Practice for PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Image: Visitors are silhouetted against the Tokyo skyline as they look on from the Tokyo Tower. (Kirby Lee-USA TODAY Sports)