Atlantic Council president and CEO Frederick Kempe recently interviewed James L. Jones , National Security Advisor to President Obama and former Chairman of the Atlantic Council Board of Directors.

How do the challenges that face you today as National Security Advisor to President Obama compare to those that General Scowcroft faced 20 years ago when the Cold War ended?

The very concept of national security is much more expansive in the 21st century than it was in the 20th century. In General Scowcroft’s time, national security was really the province of Secretary of Defense, of Secretary of State and part of the State Department and the National Security Council. Everybody else was essentially a spectator.

In this new century, given the end of a bipolar world, the end of a unipolar world – multipolarity is with us. And national security encompasses much more than just the size of the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, the Marine Corps and the State Department. It encompasses economic realities; it encompasses the asymmetric challenges that face us in ways that have replaced the threat of the Cold War of a single entity on the other side of a well-defined border.

Borders are not meaningless yet, but they’re certainly not as important as they used to be in terms of confronting the threats that face us: proliferation, energy, climate, cyber security, the emergence of non-state actors, human trafficking and the economic effects of our policies all contribute to defining national security. So the National Security Council of the 21st century is a much broader organization and has to deal with multiple challenges that arrive every single day.

Your job is more complicated than those of your predecessors who fought the Cold War? This period is more complicated for U.S. leadership?

Yes, it’s far more complicated with much more diverse challenges.

Is it more perilous as well?

It’s a more dangerous world. The reason I say that is because even with the threat of mutually assured destruction in the 20th century, we managed to control that. If you lose control of proliferation issues and non-state organizations acquire weapons of mass destruction, you can’t control that. We rail against North Korea and Iran, legitimately, but they are nation-states. They have to behave as nation-states. They are functioning in a world order that exists. We may not like what they’re doing, but they know the penalties should they acquire nuclear weapons. The penalties of using them would be catastrophic for them. But terrorist organizations, they don’t have the same fear.

Of all the threats we face in the world, which is the one that keeps you up late at night?

It is this nuclear proliferation issue involving non-state actors.

Is that danger growing? You appear to be focusing on this issue more than you did at the beginning of your tenure.

I think the danger is omnipresent because you don’t know to what extent other nation-states might be enabling these non-state actors to acquire such weapons and capabilities. We also know acquiring these capabilities is a driving goal of these organizations. They are pushing at it, and you never know who’s enabling them to make progress. You can’t be everywhere all the time. So it is something to be concerned about. I’m not really worried about the nuclear aspect as much as I am the other biological, chemical and related threats, which are easier for them to get a hold of.

What do you do about it?

I think we’re doing everything we can, at least nationally. There’s been a developing cohesion among the security forces of this country that’s probably unparalleled in our history in a short period of time. I think one of the reasons I worry about it is because I know the successes we’ve had. Which means that there’s got to be more out there because we’re probably never going to be 100 percent successful.

Can you give an example of that success?

The most recent ones suggest direct links from individuals here in this country going through the al-Qaida network back into Pakistan. They’re still able to direct certain operations, although they’ve been disrupted. Fortunately, they haven’t carried out operations but it’s still a threat.

If you take a look at the role of the military in this new world, with these sorts of threats, how does it differ from the world that brought us the Cold War, the fall of the Wall?

I think the role of the military is much more diverse and much more complex because it’s got to be able to operate in different environments. It’s no longer one army. The army of NATO arranged against the army of the Warsaw Pact on either side of the line of scrimmage, the border.

The military forces of today have to be very agile and able to operate in different environments, from guerrilla warfare to conventional war, from highly specialized operations to some aspects of nation-building. So they have to be better educated. They have to be able to project power when needed and project stability when needed. The two are vastly different. So we need our young people who are out there to be nimble of mind and able to understand the environment they’re working in, far more than ever before.

Does the U.S. have the same leverage we had at the Cold War’s end to achieve results? Are we losing some of our relative influence in the world because of our financial difficulties and the fact that other powers are rising?

The world has changed. Perhaps the most dramatic threat to our national well-being over the next two decades is going to be around the issue of competitiveness. We’ve had a good run for over half a century. We’re very comfortable and are used to being number one. We took a little bit of a dip over the last decade in terms of how people looked at us around the world, but we saw that this could be very quickly restored. The election of President Obama, and the actions of the President, so far, globally, have dramatically increased the esteem in which we are held.

What’s your view on the Nobel Peace Prize?

The Nobel Peace Prize is not given lightly and I think it was given because of the ability of the President to capture the imagination of much of the world’s population about the human potential here to live in peace, to forge better opportunities for our children and to hand over a better world for the next generation. That’s pretty inspirational. I know that the President is determined to use the weight of the Nobel Prize to continue working every day to advance a robust foreign policy agenda that seeks greater peace and prosperity around the world.

With this reduced relative power, is it harder for the U.S to get things done in the world?

We’ve seen it’s possible with the right style, using the right way of doing things. My gut feeling, however, is it is harder because the world is so complex. There are rising competing powers. There are other sleeping giants that are coming up all at the same time: the Indias, the Brazils, the Chinas, the European Union. Hopefully, our own hemisphere will also have a similar rebirth, to say nothing of the potential of Africa. By comparison, it was easy to get things done in a bipolar world. You had two big guys, two big countries and everybody fell in line relatively quickly. But now, it’s much murkier and you have to work much harder to arrive at the successes you wish to achieve.

The National Intelligence Council has said in its Global Trends 2025 report that China will be the greatest single new factor shaping affairs in the next 20 years. Will it do so as a rival or a partner?

There’s going to be a little bit of everything. Our relations with China are developing and they’re developing positively. China is going to be a friendly competitor. That’s what the world is all about. That’s not something that we should necessarily fear but we should rise to the challenge. The same is true for Brazil, India and others.

We’ll have, hopefully, some convergence with them on what our core security problems are: clean energy, maintenance of the climate, a lot of cohesion on the threats posed by terrorists and the like. The world we live in is such a small place that we required a convergence on the big issues of our time.

How does NATO fit into this world you are describing?

NATO has served the cause of freedom extraordinarily well. It was a key contributor to the Cold War’s end. It was an inspiration for what I have called the “forgotten half of Europe,” which is now seeing, after so many years, a Europe whole and free come to fruition. The question now is how this NATO reorganizes itself in such a way to confront the asymmetric, multipolar world that we face and whether it will do so in a manner that reflects the proactive requirements of our time. NATO was conceived as a defensive, reactive alliance that was never going to strike the first blow. Being defensive and reactive against the array of multiple threats and challenges that face us every day is not a good position to be in.

That’s a quite different NATO than what we have now.

We’re not looking for a NATO to project its militaries all over the world to fight. But I would say we’re interested in a NATO that is, through a series of interactions with not only member-states but states who wish to have a working relationship with NATO on the basis of mutual values and commonly recognized threats, able to deter future conflicts in their embryonic stages and to take on the transnational threats that face us in an asymmetrical way today: terrorism, human trafficking, flow of energy, protection of critical infrastructure and proliferation.

That’s a pretty radical rethink of NATO. Is that what you want to see in the new strategic concept?

Yes. None of the things I just talked about are in NATO’s mission portfolio doctrinally right now. If NATO can achieve that through reform, then it will have relevance in the 21st century. If it doesn’t, then I think it could be a testimony to the past but not much else.

Engagement. General Scowcroft in his interview for this publication talked a great deal about how the proper form of engagement with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev under President Reagan and President George H.W. Bush was crucial to ending the Cold War. President Obama has also had a different view about engaging with adversaries than did his predecessor.

Engagement is a must in a globalized world. You do not have the luxury of time to sit back behind fortress America and ponder excessively on what’s going on around you. The world’s moving too fast and there are too many challenges that are out there that need immediate attention. Because communication is so easy now, travel is much easier, the personal engagement at the head of state level, the time spent in working the issues is going to be much more frequent, much more demanding on heads of state in order to make good progress. And that’ll cascade down through the national structures as well. But I think that aspect of governance is definitely on the increase.

Iran is one place where U.S. engagement has increased. Russia is a far different situation, but we also have increased engagement through pushing what Vice President Biden called the “reset button.” How are those efforts going?

This may sound simplistic, but I’ve always been struck by the fact that the way you conduct national relationships is not dissimilar to the way one develops personal relationships. It is important to establish a relationship based on mutual respect because that not only opens the door to working together, but also allows for disagreement to be expressed in a way that does not have to lead to conflict.

What the President is looking to do is to create opportunities for advancing United States interests through improved relations, while standing firm on our principles and national security interests.

I think President Obama, thus far, is off to a great start in re-establishing a basis for respectful, thoughtful, professional relations that are serving American interests around the globe – whether we are talking about re-setting our relationship with Russia, establishing a strategic dialogue with China, building stronger partnerships with countries like India and Brazil, fostering even closer bonds with Europe, promoting prosperity in our hemisphere and in Africa, and engaging with the Muslim world.

That’s why in his inaugural address he said, we are open for discussion; we’ll extend the hand of friendship but you’re going to have to show you’re serious about it also. It’s a two-way street.

I have already seen great receptivity among his fellow world leaders and people abroad to the President’s policy of engagement and his clear message that we seek cooperation to advance common interests and tackle common challenges. And I think that’s had, thus far, good effect.

Apply that to Iran? Some say it could become the defining foreign policy issue of the Obama administration.

Both Iran and North Korea are, kind of, in the same envelope. Proliferation. They are two countries that have been working toward nuclear technology and the weaponization of the technology and the means to deliver them. That is anathema to a peaceful world order. And it could, if not checked, lead to an arms race in Asia and nuclear arms races in Asia and the Persian Gulf. So this is serious business.

And Russia? As we reflect on the 20th anniversary of the Berlin Wall’s fall, did we miss options with Russia?

I can’t make an informed judgment on that as I wasn’t involved, but I know enough to say that the Russians perceived that they were mishandled. As usual, with epic issues like this there’s probably criticism on both sides that would be fair. But of late, particularly in the last decade or so, I’ve personally felt that there was too much of an effort to characterize Russia as a country that would never be an ally or a friend of the West. And I’ve always felt that, at the end of the day, Russia should be inside the Euro-Atlantic arc, as opposed to the outside looking in. I think that’s what Russia wants and we’re now in the embryonic stages of reassessing – resetting, to use the exact word – a relationship that, hopefully, will lead to just that. Only time will tell, of course.

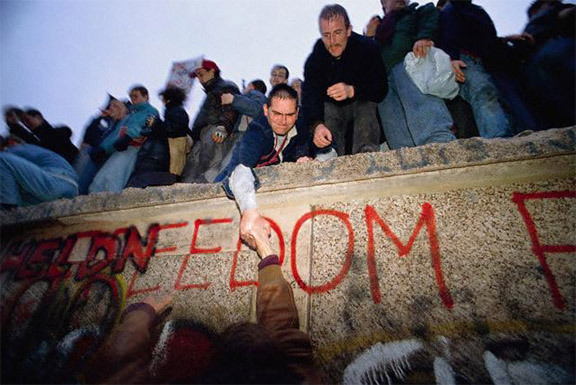

This piece is selected from Freedom’s Challenge, an Atlantic Council publication commemorating the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Image: Berlin%20Wall%20Freedom_0.jpg