Gov. Huntsman discusses the legacy of Singapore’s late leader

Lee Kuan Yew, who as its first Prime Minister transformed Singapore from a tiny, impoverished port city into an economic giant, died March 23.

In a phone interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen, Atlantic Council Chairman Jon M. Huntsman, Jr., remembers a man he was proud to call a friend and mentor. Excerpts below:

Q: Lee Kuan Yew was not just a formidable statesman who transformed Singapore, he was also a personal friend and mentor to you. How did he turn Singapore into the success story that it is today?

Huntsman: It was a combination of the power of big thinking coupled with leadership and that indispensable ingredient called risk. If you took any one of those out he probably wouldn’t have succeeded as he did, and Singapore would not be the country it is today.

The power of big thinking, having a vision, a sense of destiny or direction for a country that in his own description shouldn’t even have existed. Singapore didn’t have a population with a common ethnic heritage, a common lingua franca, or a common sense of direction, nor did it have a common history from which it was drawing. He had to take all that diversity and give it a common sense of direction. His success was achieved through the power of bold, visionary thinking and going against the odds.

Perhaps most notably, he opened the gates to foreign investment and trade at a time when the rest of the world was saying just the opposite, which is you subsidize domestic industry and benefit from the exports.

He was singularly able to create a vision and bring a leadership team together that got Singapore through its early vulnerable days relying on, as many have said, soft authoritarianism to achieve his goals. Equally important was his willingness to assume huge risk, something that is completely foreign to today’s politics where you go by polls and public opinion surveys. What you saw play out in Singapore was exactly the opposite of that model—no polls, no opinion surveys, and a willingness to assume significant risk knowing that everything could fail and the whole game would be over.

Q: While he led Singapore to great heights, this came at a cost, specifically human rights. He famously noted that while not everything he did was right, it was done for an “honorable purpose.” Was it worth the cost?

Huntsman: I remember him saying that during his lifetime he grew up learning four national anthems—something that is completely foreign to our experience in the West, and particularly the United States. He learned the national anthems of the United Kingdom, Japan, Malaysia, and Singapore. That was his foundation and the making of his world view.

He brought about a model that he later argued was very much based on Asian values: the wellbeing of the collective or the community before the individual. We’ll have this debate on Asian values versus traditional Jeffersonian Western values for a very long time.

His formative years and circumstances were far different from what we can imagine in the West. As a result, it produced a leadership style that said, “We must secure our economic future and bring the quality of life up for the average citizen or we’re not going to survive as a civilization much less a democracy or civil society.”

As he said, he made mistakes along the way. He regretted some of the decisions that he made and he has also gone on to say that everything was done for an “honorable purpose” to keep the country stable during those early years. In short, he created an ownership society that served as an enduring foundation for stability and prosperity. With today’s secure economic foundation, I suspect Singapore will expand its creative class and existing civil society and people inevitably will demand more of a representational government.

Q: Lee Kuan Yew advised several US Presidents while he was Prime Minister. How did his advice shape US policy toward the East?

Huntsman: You can go back to Richard Nixon’s 1967 visit to Singapore when he was thinking about launching a second campaign for the presidency. He wrote quite a lengthy article in Foreign Affairs magazine. Part of that came from his meeting with Lee Kuan Yew whom he got to know when he was Vice President under Eisenhower.

I believe some of the early thinking around America’s approach to China was, in part, derived from a conversation Nixon had with Lee Kuan Yew about China being ready for something new and a relationship that could help it counterbalance its concerns with the Soviet Union. You can go back to those early days and fast-forward from 1967, where that conversation could have been a critical part of what was Nixon’s and, I would argue, one of America’s most defining diplomatic initiatives in my lifetime: dealing with the balance of power relationship with the Soviet Union and how countries like China factored into it, and how the global order was rearranged based upon America’s approach to a new diplomatic relationship with China.

Whether Republican or Democrat, Lee Kuan Yew provided clarity to foreign leaders about Asia, specifically China. The whole field of China studies was relatively new when the US-China rapprochement was born in the early 1970s and then developed during the ‘80s and ‘90s. We didn’t have a lot of China expertise and administrations appreciated the guidance. Lee Kuan Yew served an indispensible purpose in schooling our top diplomatic and security professionals in how to think about Asia, how to balance our interests with China, and in understanding what was on the minds of China’s leadership when that kind of information was otherwise difficult to come by.

Q: What was his influence on China?

Huntsman: Deng Xiaoping made an historic trip to Singapore in 1978. At the time, he cited the “Singapore model” as one China should aspire to in large part because it was a population of majority Han citizens living in prosperity with essentially one-party control. It naturally had some appeal to Deng Xiaoping as he was looking to the future and imagining what China could become at some point.

Singapore played an indispensable role in guiding China during its economic reform years. For example, they were responsible for organizing economic development zones in China, which mirrored their own approach during the Special Economic Zone policy push twenty years ago. Ultimately those worked out and I think the Chinese learned an enormous amount about attracting investment, making joint ventures work, and dealing with the United States and its commercial class from that early experiment with the Singaporeans.

Q: How did he balance good relations with the US and China?

Huntsman: Lee Kuan Yew was one who recognized that the United States and China had common and mutual interests. He understood each country’s trip wires. Many of the shared interests were economic in nature and one of them was to maintain a benign external security environment for purposes of economic growth. But he long argued that the United States could pursue its interests in the Asia-Pacific region and match the Chinese in terms of what they were looking for, which was essentially the same thing—economic expansion and maintaining security in the region. The sticking point was how each side could understand one another from a cultural standpoint—one coming from 5,000 years of tradition, no democracy, no sense of human rights, a different language, and a different geography, and the other, the United States, with a short history by Chinese standards, a strong commitment to rule of law, a Constitution, and a prominent role for the individual in society—seemingly irreconcilable differences.

Lee Kuan Yew, understanding both worlds—having been raised in Asia but having done his schooling in the United Kingdom—had a strong sense of both ends of the Pacific. He was able to communicate as a trusted advisor to both sides, something that no other statesman was able to achieve during those important years of growth.

For the Chinese, he helped them understand the United States and the perspectives that helped shape us and made us unique. And he was able to do the same thing on the US side, to help us understand each generation of Chinese leadership and what was on their mind, what their priorities were, and how best to structure issues to meet and not conflict in ways that would have a negative spillover effect in the region.

Q: What will be Lee Kuan Yew’s legacy?

Huntsman: In short, he created an ownership society at a time when the rest of the world was moving in the opposite direction. His willingness to lead with a bold vision based on the rule of law and a clean government created the world’s most recent example of a country going from third world to first world under a single generation of leadership.

Ashish Kumar Sen is a staff writer at the Atlantic Council.

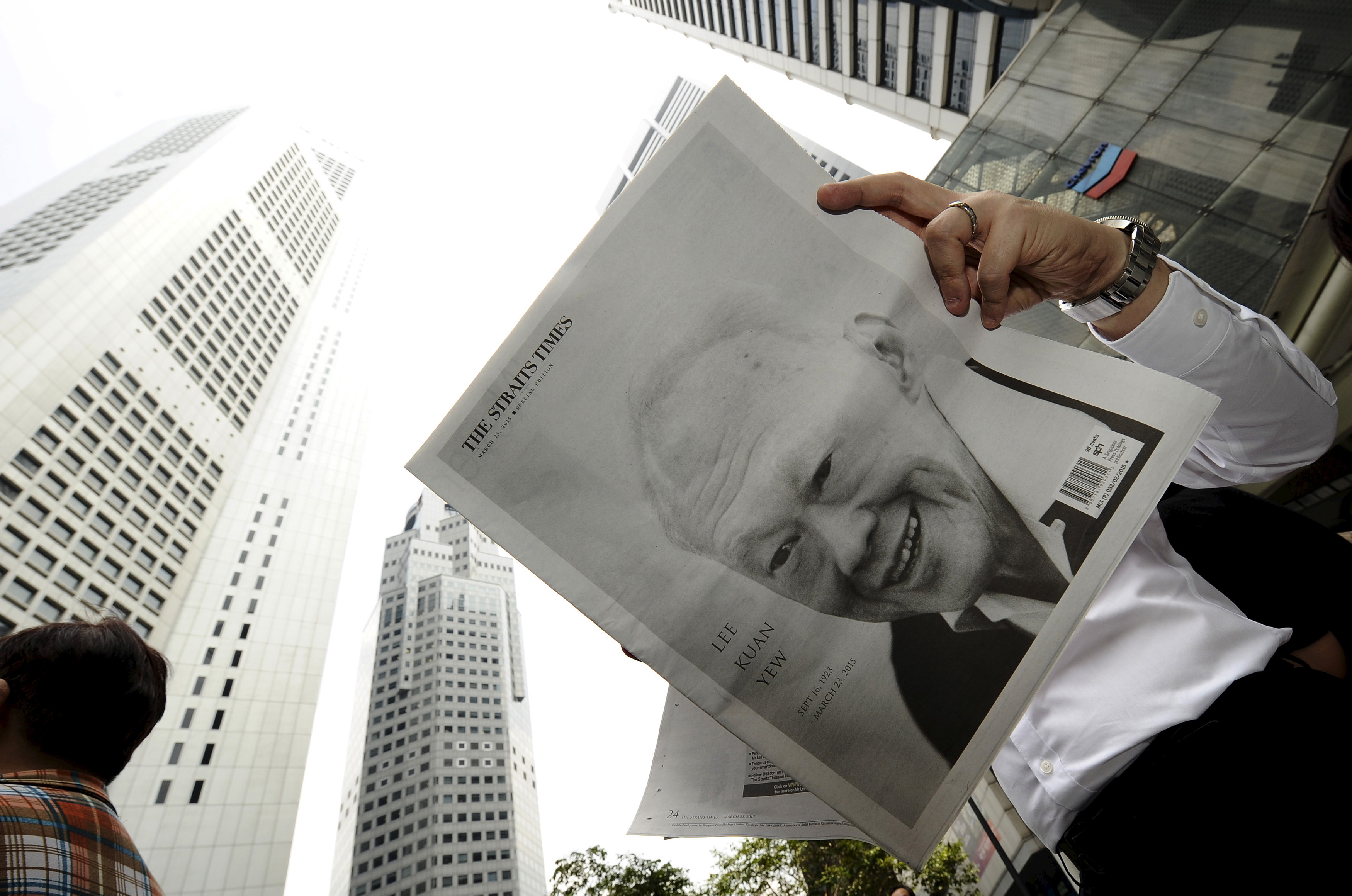

Image: A man reads a newspaper bearing the image of Singapore's former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew at Raffles Place in Singapore March 23. Lee died March 23 aged 91, triggering a flood of tributes to the man who oversaw the tiny city-state's rapid rise from a British colonial backwater to a global trade and financial center. (REUTERS/Timothy Sim)