Venezuela is undergoing a period of profound crisis. Protests occur on a daily basis in every major city in the country. Thousands of Venezuelans have fled in search of economic opportunities and stability. In response, the government has taken drastic measures, including proposing a rewrite of the constitution.

Venezuela is undergoing a period of profound crisis. Protests occur on a daily basis in every major city in the country. Thousands of Venezuelans have fled in search of economic opportunities and stability. In response, the government has taken drastic measures, including proposing a rewrite of the constitution.

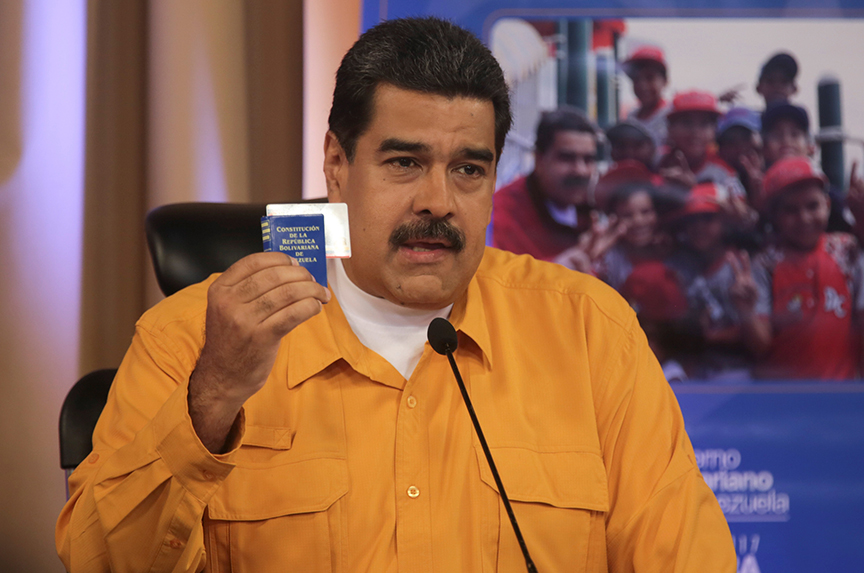

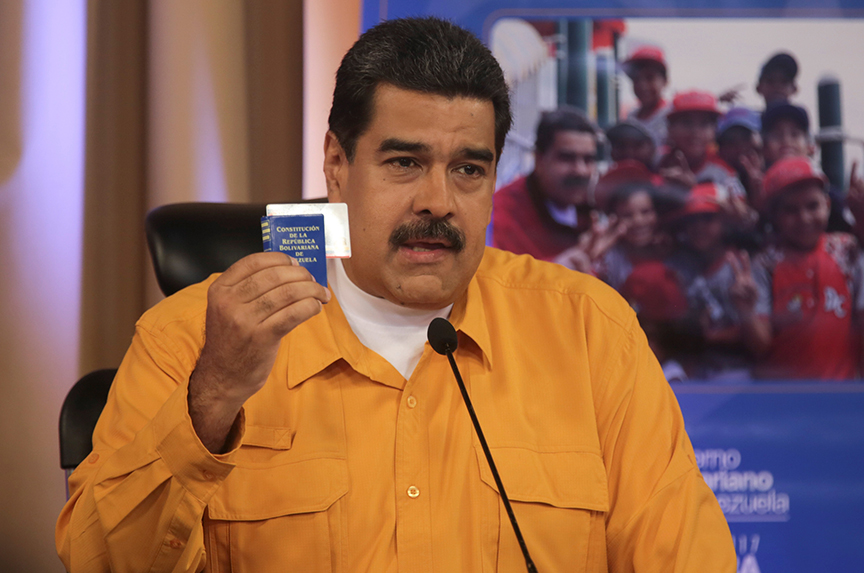

In a sign that the crisis may be worsening, the opposition has called for a referendum on July 16 on Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro’s plan to rewrite the constitution. This referendum comes two weeks before the government holds a vote to elect delegates to a special assembly that will be tasked with rewriting the constitution. Maduro has ordered all state employees to participate in the July 30 election, despite the fact that the constitution does not require Venezuelans to vote.

This is part of a pattern of Maduro demanding unconditional loyalty from government officials, oftentimes removing those who acknowledge a worsening situation. A wave of dismissals has disfigured Venezuela’s democracy—today it is barely recognizable.

The government’s latest target is Luisa Ortega, Venezuela’s attorney general, who has served in her position since 2008. Nicknamed “Maduro’s jailer” after Leopoldo Lopez and other opposition members were convicted of public instigation and other crimes in 2014, Ortega now finds herself in the hot seat.

Pedro Carreño, a member of the National Assembly and of Maduro’s socialist party, has called for the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ) to try Ortega for violating the constitution, alleging she threatens public ethics and morals. This came after she spoke out against the supreme court’s gutting of the National Assembly’s powers and against what she terms “state terrorism.” She is now accused of lying and forging documents to withdraw her initial support for thirteen new supreme court justices, sworn in at the end of 2015; if found guilty, she would be removed from her position and possibly serve jail time.

While many in the opposition have come to support Ortega, several continue to reject her as an anti-regime figure due to her strong links to Chavismo. Regardless, her removal based on what many describe as weak and questionable evidence, could arguably be yet another move by the government to further consolidate power and control the flow of information regarding the situation on the ground. The government recently dismissed the Health Minister Antonieta Caporale after her department published an official report showing a drastic increase in infant mortality rates over the last year.

Allegations of dictatorship and corruptions have been raised against Maduro for years, dating to before he took office, but such statements have gained credibility since December 2015. When the opposition won two-thirds of the congressional seats in 2015, the outgoing socialist congress held a special session to select and swear in thirteen of thirty-two socialist supreme court justices after several magistrates suddenly “requested” early retirement in October. The year before, Maduro appointed sixteen new justices, meaning the president has now personally appointed twenty-nine of the thirty-two justices.

While the opposition controls the National Assembly, the body has been paralyzed since November 2016. Claiming fraudulent elections, the TSJ ordered the National Assembly to stay the swearing in of three congressmen from Amazonas state. After the National Assembly chose to ignore the order, the tribunal has held it in contempt ever since, essentially invalidating any action it takes.

In May, the government allowed the socialist-dominated TSJ to assume all legislative powers, citing the National Assembly’s “continued state of contempt.” The international community condemned the move and Peru even recalled its ambassador, calling the act an “arbitrary measure that distorts the rule of law and constitutes a break from the constitutional order.”

But the most blatant violation of the democracy is Maduro’s call for a new constitution. It is unclear if the government will acknowledge any other outcome other than support for a constituent assembly.

All of this is occurring while the world waits for the TSJ to decide if it will formally try Ortega for violating the constitution. Should she be tried and should Maduro proceed with his constituent assembly, he would put the final nail in the coffin of Venezuela’s democracy. Such flagrant violations of Venezuela’s constitution are hard to ignore and may finally prompt international action.

Luis Almagro, the secretary general of the Organization of American States, could finally gather enough votes to pass a resolution criticizing the Venezuelan government’s management of the crisis. One thing is certain: it will be harder and harder for Maduro to continue to pass his regime off as a democracy.

Sara Van Velkinburgh is an intern in the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

Image: Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro held up a copy of the country’s constitution during a meeting with supporters at Miraflores Palace in Caracas, Venezuela, on July 11. (Miraflores Palace/Handout via Reuters)