In the wake of the murder of U.S. Ambassador to Libya J. Christopher Stevens, Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney inexplicably and ironically declared, “President Obama has demonstrated a lack of clarity as to a foreign policy.”

Romney and his team, reasonably enough, quickly jumped yesterday on a tepid statement from the U.S. Embassy in Cairo that seemed to apologize for the American tradition of free speech in the wake of the storming of the embassy. We later learned that the statement actually preceded the attack by hours and was, apparently, not approved by the Obama administration.

That Romney didn’t alter course by morning and actually doubled-down on his line of attack once the murder of our ambassador and three other American public servants was known is puzzling, however. Alas, the same can be said for Romney’s entire foreign policy.

Last October, upon the release of his foreign policy white paper, “An American Century,” I read the tea leaves and pronounced in this space that “Romney’s Realist Foreign Policy Is a Lot Like Obama’s.” Eleven months and a national convention later, I’m not so sure that Romney has a foreign policy. To the extent that he’s talking about international affairs at all, his pronouncements are so scattershot that they defy assigning to a school of thought.

The Romney campaign has taken James Carville’s 1992 mantra, “It’s the economy, stupid,” to absurd lengths, deciding that talking about anything else is a distraction. And perhaps its right: polls show that most Americans like President Obama personally but are extremely worried about the economy.

Further, for the first time in decades, Democrats seem to have the advantage on national security policy. The Iraq debacle tarnished the Republican brand and Obama ordered the missions that killed Osama bin Laden and, indirectly, Muammar Qaddafi. So, Team Romney is alternately ignoring the topic altogether — for example, he didn’t even mention the ongoing war in Afghanistan in his nomination acceptance speech — or taking pot shots at anything that can be portrayed as an Obama weakness.

Ironically, in my view, Afghanistan is the one foreign policy area where Obama is quite vulnerable. Three years ago, he decided to double down on a war that most experts thought unwinnable by that point, predictably resulting in more Americans killed in action than during the eight years of fighting that preceded the so-called Afghan Surge. Further, the decision was clearly a political one, aimed at not giving Republicans an opening to attack him as weak or “surrendering” in a fight that he himself had described as “necessary.” The war was already unpopular with the American people when the surge began and more than two-thirds now think we should not be there.

Inexplicably, however, Romney is attacking Obama from the other direction. Or, rather, both directions.

On the one hand, he argues the president didn’t go far enough in Afghanistan: “This past June, President Obama disregarded the counsel of his top military commanders, including General David Petraeus, and announced a full withdrawal of those 30,000 surge troops by September 2012. That date falls short of the commanders’ reported recommendation that the troops remain through the end of 2012 and the Afghan ‘fighting season’ to solidify our gains.”

On the other, it’s not at all clear what a President Romney would do there. One would think that, by the 11th year of the war, he and his advisers could have come up with a plan. Instead, he promises that “Upon taking office … he will review our transition to the Afghan military” by “holding discussions with our commanders in the field” and “will order a full interagency assessment.”

Similarly, on Iran, Romney charged that Obama “has not drawn us further away from a nuclear Iran,” which he labeled his opponent’s “greatest failure.” But it’s by no means clear what Romney would do differently, should he win office. Aside from promising “crippling sanctions” — something that Obama and our European allies have already delivered — he’s not really saying.

Romney’s cozying up to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyu and other attempts to position himself to Obama’s right, such as his recent declaration “We must not delude ourselves into thinking that containment is an option,” lead many to speculate that he’s itching for war with Iran.

My sense is that this is just posturing. After all, there’s virtual unanimity among foreign policy professionals on both sides of the aisle that there are no viable military options. Yet, while there’s something to be said for keeping one’s options open in tense diplomatic standoffs — the Obama administration refuses to publicly take military force off the table — it’s frustrating that Romney simultaneously charges that his opponent is weak while refusing to give even a hint as to his alternative vision.

Then there’s Romney’s odd claim that Russia is “our number one geopolitical foe,” leading the president to charge that he’s “stuck in a Cold War mind warp” and John Kerry to quip at the Democratic National Convention, “Mitt Romney talks like he’s only seen Russia by watching Rocky IV.” Now, there’s actually an argument to be made that Russia is a greater obstacle to American foreign policy goals than al Qaeda, which is at most a nuisance in geopolitical terms, or China, which is more self-confident and less reckless than Putin’s Russia. Russia’s designs on its “near abroad” and the dependence of many of our European allies on Russian energy — which has been cut off several times now in nasty power plays — are actually serious issues.

I tend to agree with Romney that the Obama “reset” has “failed to move Russia toward a more beneficial working relationship with the United States and our allies,” although I strongly disagree with Romney’s criticisms of New START, which struck me as a no-brainer.

Regardless, it’s not at all clear what Romney proposes to do differently than his opponent. He wants to decrease Europe’s energy reliance on Russia by supporting Nabucco and other pipeline projects. So do I. But so does Obama. Beyond that, he talks in vague platitudes about building stronger relations with Central Asian countries and supporting civil society in Russia. But those are longstanding, bipartisan goals of U.S. foreign policy.

The Romney campaign’s foreign policy approach ultimately suffers the same basic flaw as its domestic policy approach: in trying to be all things to all people, it ultimately satisfies no one. Those of us in the increasingly marginalized Realist foreign policy camp are left clinging to the hope that the appointment of seasoned hands like Bob Zoellich to the team signals that Romney will be the serious pragmatist that he was as governor of Massachusetts. But the empty saber rattling and cozing up to Netanyahu and John Bolton are attempts to satisfy the neoconservative wing that Mitt’s one of them.

The net result is that no one really knows what a Romney foreign policy would look like. Increasingly, I’m not sure that even Romney knows.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council. This essay originally appeared at The Atlantic.

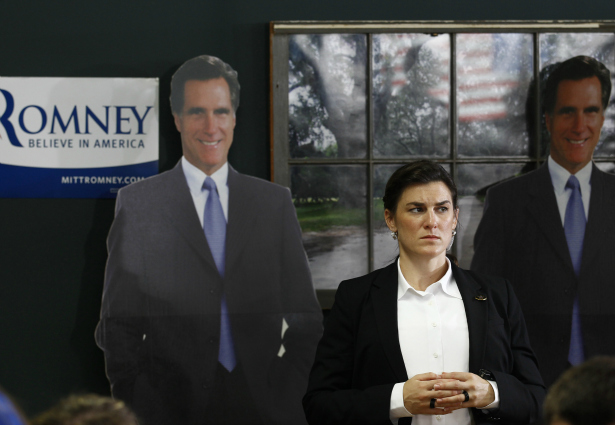

Image: cardboardROMNEY.banner.reuters.jpg