United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, adopted in 2000, had high hopes. Recognizing that women and children are the worst affected by armed conflict, the measure urged member governments and the UN itself to include more women in decision making and operations. It also “called on all parties to armed conflict to protect women and girls from gender-based violence [and]… emphasized the responsibility of all states to end impunity and to prosecute those responsible for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, including those relating to sexual violence against women and girls.”

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, adopted in 2000, had high hopes. Recognizing that women and children are the worst affected by armed conflict, the measure urged member governments and the UN itself to include more women in decision making and operations. It also “called on all parties to armed conflict to protect women and girls from gender-based violence [and]… emphasized the responsibility of all states to end impunity and to prosecute those responsible for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, including those relating to sexual violence against women and girls.”

But so far, not so good. A February review of how UNSCR 1325 has been implemented worldwide, researched by the nonprofit Security Council Report, shows that rather than embracing the inclusion of women as “one of the central tenets which support conflict prevention and underpin long-term stability,” the UN system still “views gender issues as an ‘add-on’ component.”

Women around the world continue to face torture and abuse: the brutal murder of Farkhunda in Kabul in 2015, the enslavement and mass rape of Yazidi women in Iraq, the kidnap and forced marriage of hundreds of young Chibok girls in Nigeria.

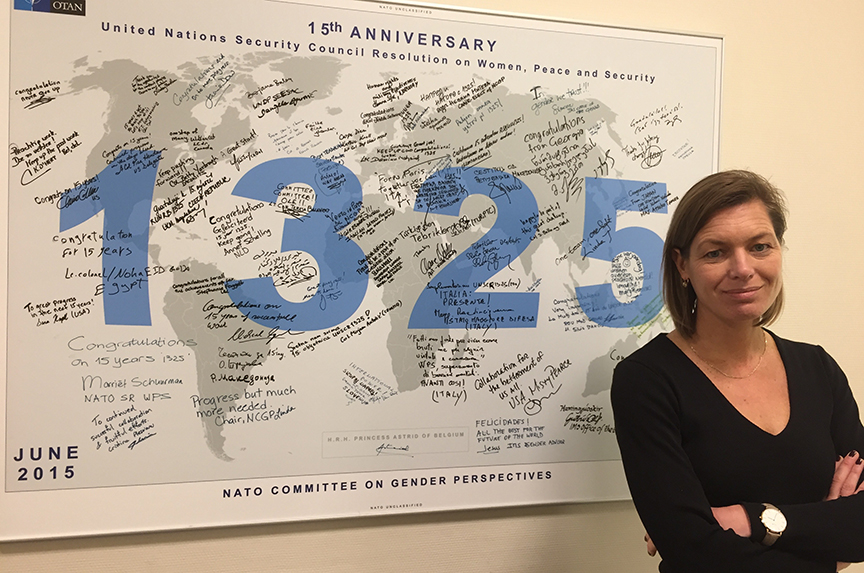

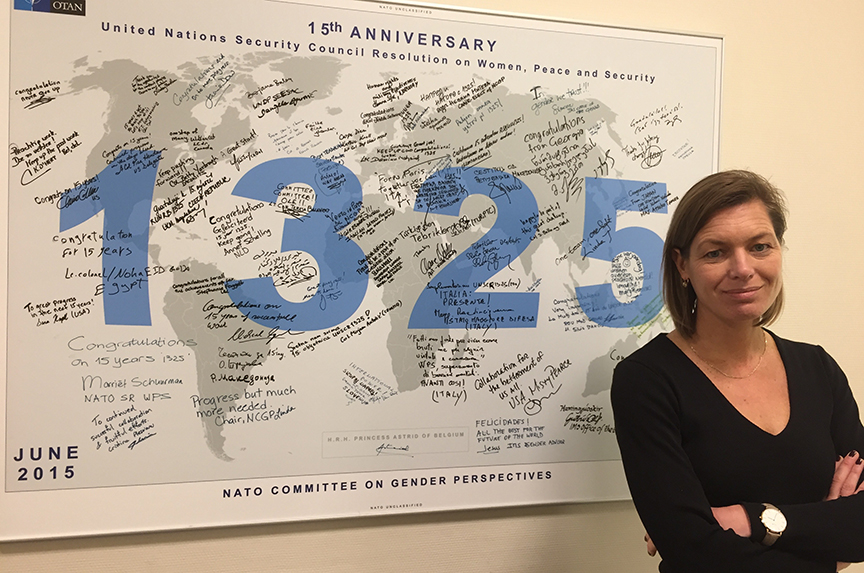

That’s not to say there haven’t been advances, most measurably in institutions. A dozen years after UNSCR 1325 was passed, among other measures taken to ensure its implementation internally, NATO also created a distinct position to help the alliance adopt and adapt to the desired changes. The current Special Representative for Women, Peace and Security, Dutch Ambassador Marriët Schuurman, describes her role as helping to define and implement “inclusive security” both internally and externally.

“There’s a big commitment,” Schuurman said. “We’re struggling to get there, but definitely the political engagement and engagement of men and women at all levels to make this change is really encouraging. “

Schuurman said improvements in gender balance start from the common understanding that it makes the alliance more effective, and more broadly, that “we can only be at peace and secure when we are inclusive.” She helps diversify the workforce by spreading the view to managers and recruiters that the “gender lens” is not an extra burden, but an opportunity. “I try to translate into day-to-day work and objectives what this agenda could mean,” she explained, “for not only doing the right thing, but doing the right thing right and better.”

Schuurman emphasized that while her hope is that eventually it won’t matter whether leaders are men or women, that moment is not yet here. For now, she pointed out proudly that NATO has its first female deputy secretary general—longtime US defense official Rose Gottemoeller—and its first female four-star admiral in a command position—the US Navy’s first female four-star, Michelle Howard—in charge of Allied Joint Force Command Naples. At February’s defense ministerial, a quarter of the twenty-eight defense ministers were female as are six of the twenty-eight ambassadors to NATO.

Meanwhile, UNSCR 1325 hasn’t helped females who are victims of conflict. What Dutch Maj. Gen. Patrick Cammaert said about the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2008, that it’s more dangerous to be a woman in a warzone than a soldier, is still true around the world. Schuurman said better implementation of UNSCR 1325 would help that, too. When peace negotiations involve women, she explained, there’s a 35 percent increase in the likelihood that there will be an agreement and that the agreement will hold. “There is a clear rationale to be inclusive,” she said, “it’s just a matter of reminding ourselves and making sure all the stakeholders actually have a seat at the table and not only those who picked up the weapons.”

Schuurman believes things are moving quickly now to a better future for women in and out of warzones and that this seventeen-year-old UN resolution is playing an important role at NATO, along with an enthusiastic secretary-general who used to himself be a gender advisor to the Norwegian government.

Schuurman said that in the very near future, “gender sensitivity will just be part and parcel of the toolkit of every security provider, to be able to understand what gender is and how it reflects on what you’re doing, what you’re trying to achieve, how you can use the ‘gender lens’ to do what you already do very well even better.”

She said this “infusion of diverse talent,” making sure 100 percent of the population is perceived as potential employees, is the kind of organizational change and adaptation NATO needs to move ahead. She believes real differences in diversity can be made in as few as the next two years. Her message to anyone feeling uncomfortable with that is to just to accept that it’s irreversible. “This has to become the new normal,” she said.

Teri Schultz is a Brussels-based freelance journalist. You can follow her on Twitter @terischultz.

Image: NATO’s Special Representative for Women, Peace and Security, Marriët Schuurman, said that in the very near future, “gender sensitivity will just be part and parcel of the toolkit of every security provider, to be able to understand what gender is and how it reflects on what you’re doing, what you’re trying to achieve, how you can use the gender lens to do what you already do very well even better." (Atlantic Council/Teri Schultz)