President George H.W. Bush ascended to the presidency with a reputation for experience, judgement, integrity, and a steady hand. However, the looming question was whether he could inspire people with, in his own words, “the vision thing.”

That quotation, first reported by Robert Ajemian in a Time feature in 1987, dogged George H.W. Bush throughout his presidency. Yet, President George H.W. Bush – more than any post-Cold War president – successfully articulated a vision of a “Europe whole and free” that became an historically successful strategy guiding US policy for the subsequent twenty-five years. Indeed, his words, first spoken when I was a high school student gripped by the possibilities of the end of the Cold War, have inspired my own career for the past three decades.

On May 31, 1989, President H.W. Bush – speaking in Mainz to the citizens of a then still divided Germany – set out his vision for American leadership in support of a united Europe built on the foundation of lasting security and shared values of democracy, freedom, and prosperity.

He said, “For forty years, the seeds of democracy in Eastern Europe lay dormant, buried under the frozen tundra of the Cold War. And for forty years, the world has waited for the Cold War to end. And decade after decade, time after time, the flowering human spirit withered from the chill of conflict and oppression; and again, the world waited. But the passion for freedom cannot be denied forever. The world has waited long enough. The time is right. Let Europe be whole and free.”

Only four months into his presidency, he delivered remarks that shaped not only his administration’s strategy, but became an American bipartisan grand strategy for the coming decades. These remarks were an audacious challenge to those living behind the Iron Curtain and set a high bar for America’s aims in Europe – words all the more notable coming from a famously cautious US president.

Remarkably, President George H.W. Bush spoke these words days before Poland’s first free elections on June 4, five months before the fall of the Berlin Wall that November, more than two years before the collapse of the Warsaw Pact, and more than two and half years before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The story of a Europe whole and free began as a united Germany, the restoration of the nations of the Central and Eastern Europe, the independence of Russian and other nationalities from Soviet communism. “Europe whole and free” at first embodied the hopeful future of the continent no longer divided by the Iron Curtain with half beholden to totalitarianism. Yet, soon, dramatic political and security shifts on the ground forced Washington and Brussels to define a set of policies toward Western Europe’s post-Communist, eastern neighbors.

For the next twenty-five years, American policy toward Europe and Eurasia would be guided by the vision of a “Europe whole, free” – a concept that from the start, included Russia.

President Bush drew on a common transatlantic grand strategy from much earlier, making it relevant for the dawn of the end of the Cold War. The United States fought World War II not only to defeat the Nazi menace, but to help Europe emerge from war in a way that would never force the United States to fight again in Europe. After forty-five years of Cold War, President Bush forged a bipartisan US policy to fulfill our original aims of 1945.

While not anticipated at the time, NATO and European Union enlargement became the most effective tools for achieving this vision. The prospect of joining these great institutions became an engine for reform, returning former Warsaw Pact nations to their European home. But enlargement was always coupled with forging a new cooperation with Russia.

President George H.W. Bush’s formula for success broke down in 2008 – and it broke down violently. The crisis in Ukraine suggests just how broken the strategy may be.

Today, Europe remains incomplete, its institutions uncertain, and America ambivalent about its role in Europe. Even past advocates question today’s relevance of the paradigm of a Europe whole and free. Russia after all is no longer a partner in pursuing a “common European home,” a term coined by Gorbachev. Rather Putin is rejecting the post-Cold War order. Unfortunately, he has positioned himself and therefore Russia as an adversary rather than a partner.

So our task is whether we can or even should retain the vision of a Europe whole and free – and complete the integration of Europe – holding out the prospect of a place for a different Russia in the future – in the face of a Russia that rejects this vision today.

Faced with this historic challenge, much like 1989, the United States needs the kind of leadership, integrity, and yes – vision – that President George H.W. Bush offered then for America’s role in the world.

Damon M. Wilson is executive vice president for programs and strategy at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DamonMacWilson.

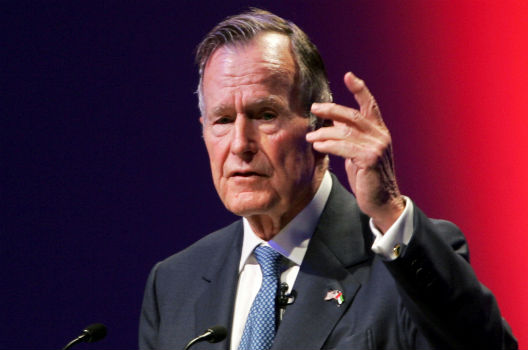

Image: Former U.S. President George H.W. Bush speaks at the World Leadership Summit in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates November 21, 2006. (REUTERS/Stringer/File Photo)