US Ambassador to Colombia, Kevin Whitaker, cites need to move quickly on achieving an accord acceptable to all sides

Two ground realities in Colombia—former guerrillas gathered in remote rural cantonments with scarce infrastructure and nationwide elections in the spring of 2018—make it imperative that a peace agreement that is acceptable to all sides is quickly found, according to Kevin Whitaker, the United States’ ambassador to Colombia.

On October 2, Colombians narrowly rejected the peace accord reached by their president, Juan Manuel Santos, and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) following six years of negotiations.

Polls preceding the plebiscite consistently and confidently predicted a triumph for the “yes” camp in support of the accord. In anticipation of such an outcome, FARC guerillas started to gather in cantonments—isolated rural communities with little infrastructure—as agreed to in the accord. There they would lay down their weapons and prepare for lives as civilians. Now, much like the peace deal, the lives of these people are in limbo.

“Over time, it is difficult to maintain people in these rural settings without a lot of support structure around them,” Whitaker said in an interview. “The time pressure is there for everyone.”

There is the additional pressure of the political cycle. Senators, representatives, and even the president will be up for election in March of 2018.

“To me it makes good sense to take in both of those factors to move as rapidly as possible to have the best possible accord on alterations that would make this a more broadly accepted accord,” Whitaker said.

The question of transitional justice—holding the rebels and members of the Colombian military accountable for their crimes and ensuring justice for their victims—is a key obstacle to achieving a peace accord that has resounding approval.

The “no” camp, led by opposition senator and former President Alvaro Uribe, believes the government has been too lenient with the FARC. Further, it contends that the rebels should not be permitted to run for political office.

Soon after the plebiscite, Santos, Uribe, and FARC leader Timochenko pledged to continue working toward peace. The “no” camp has since recommended modifications to the accord. Santos has described some of these recommendations as unviable.

“While [Santos] didn’t say what was hard and what was unviable, the transitional justice component, it seems to me, is certainly one of those where there seems to be a distance between what the ‘no’ has said and what the accord says in some cases,” said Whitaker.

The FARC declared a unilateral ceasefire a year ago. This has since been transformed into a bilateral ceasefire and continues to hold despite the outcome of the plebiscite.

Kevin Whitaker spoke in a phone interview with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts from our interview:

Q: Colombians narrowly rejected the peace deal in a plebiscite. How can the United States help get this process back on track?

Whitaker: It is true that the Colombian people, by a narrow margin, voted “no” on the idea of the peace accord and the same evening, on October 2, the FARC leader Timochenko, President Santos, and former President Uribe, who is the de facto leader of the “no” group, all came out and indicated their conviction to seek avenues to reform the accord in ways that would make it acceptable to the Colombian people. I thought that was extraordinarily responsible and mature on the part of all of them. That process of consultation between the government and elements of the “no” group has continued to this day.

It is important to note that while Uribe is an important factor in the “no” coalition, it is bigger than just his political party or his political movement.

President Santos announced [last week] that a number of proposed changes to the accord have been received by the government, including from Uribe and his team; that all of the proposed changes were being categorized and put into different baskets; that some of them were achievable but hard, and some of them were not viable, but regardless he intended to move on based on the proposed changes received to date.

Q: In hindsight, was a plebiscite a bad idea? In light of the outcome of the Brexit referendum, did the US government ever advise President Santos against holding a plebiscite?

Whitaker: This was a Colombian government decision. President Santos announced very early on that the Colombian people would have the last word on the accord once it was fully negotiated.

In the run up to the plebiscite itself, and before the actual campaign, the position of everyone, including the government, was no means no and that if the accord was rejected then it’s back to a clean sheet of paper, back to ground zero.

In a very responsible way, all three parties have decided to use the existing accord as a basis and see what alterations or changes or fixes can be made to it to make it acceptable to the broadest number of Colombian people.

Q: Despite the outcome of the plebiscite, Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. There is worldwide support for peace in Colombia. Has this made it more or less difficult to deal with Alvaro Uribe and the “no” camp?

Whitaker: In my view, President Santos richly deserved the Nobel Prize. No one has been more committed to the cause of peace than him. No one has worked at it for a longer period of time. Frankly, no one has paid a higher price than Juan Manuel Santos for his commitment to achieving a negotiated peace.

People here [in Colombia] are looking at their issues and how the accord affects them and what their concerns are. So the decision of the committee in Oslo is frankly not among the top four or five things they think about when they contemplate this accord. I am not trying to discount Santos’ winning it. It is obviously an enormous honor, but I think Colombian calculations are other.

Q: President Santos has called some of the new demands by the opposition unviable. Which demands do you consider to be deal breakers, and what are the prospects of the FARC returning to the negotiating table?

Whitaker: [Santos] didn’t actually say which were difficult but achievable, and which were nonviable. Clearly, one of the more difficult topics at stake here is that of transitional justice.

The transitional justice system that the Colombians have come up with with the FARC in this case is very complicated, it is innovative, and it is very controversial with the “no” faction. This is one of [the “no” campaigns] main banners—that fundamental changes to the transitional justice scheme have to be made.

I would put their concerns in this regard in two or three camps. One was the “no’s” view that creating a new transitional justice system with new prosecutors and new defenders and new judges is dismissive of the Colombian judicial institutions, which they are very proud of here. So [they believe] nothing should be done which violates the creditworthiness of Colombian democratic institutions.

Another of their arguments, which comes up a fair bit, is that they feel that there hasn’t been enough clarity about the deprivation of liberty to which those found guilty of gross violations of human rights would be subjected.

Under the transitional justice accord, individuals who are responsible for common crimes or political crimes—like rebellion or insurrection, everybody in the FARC is guilty of insurrection because they rose up against the government—everyone agrees that those offenses should be pardonable or “amnestiable.” There is no debate about gross violations of human rights, which are codified in the accord. The question then becomes what happens to those individuals who are convicted of gross violations of human rights? What the government has said is this won’t be a traditional sentencing regime. It will be a shorter regime. There will be six to eight years instead of thirty years for murder, to take one example, and there will be some sort of a deprivation of liberty. But it is not at all clear what that means. That is a point that the “no” campaign has really zeroed in on.

Another point that the “no” campaign has expressed deep concerns about is the possibility that those found responsible for gross violations of human rights would be permitted to participate in Colombia’s democratic institutions; to run for office, for example, which [the “no” campaign] thinks is a violation of the constitution.

While [Santos] didn’t say what was hard and what was unviable, the transitional justice component, it seems to me, is certainly one of those where there seems to be a distance between what the “no” has said and what the accord says in some cases.

Q: Is it your sense that on the part of the Santos government and the FARC there is no flexibility on this issue?

Whitaker: It’s a negotiation. Everybody starts off with maximalist positions. So the “no” team has stated its piece; the FARC has said not a single word can be changed of the transitional justice agreement: “We have been working on this for six years. This is one of the things that got us to the negotiating table or got us to sign the accord. The International Criminal Court has… not evidenced great objections to it.” So their position is “we cannot change this.” I am not surprised by that. That’s the way every negotiation starts. Does that mean it will end up that way or will it change? That I don’t know.

Q: Has the result of the plebiscite made it more difficult or easier for Timochenko to rally his troops behind peace?

Whitaker: Timochenko has talked a little bit about the time pressure that is involved here. There has been a bilateral ceasefire, in effect, for a year now and in anticipation that October 2 would yield a “yes” vote, all the timelines would commence for cantonment and demobilization and disarmament. FARC fighters in many, many cases were starting to move toward the cantonment areas. Over time, it is difficult to maintain people in these rural settings without a lot of support structure around them. The time pressure is there for everyone.

Q: Are you concerned the ceasefire could fall apart if a new peace agreement is not reached soon?

Whitaker: All sides have indicated their commitment to maintaining the bilateral ceasefire. The UN has agreed to assume a monitoring and verification role. The UN mission here was all set up to help with monitoring and verification of the accord, once in place. Since we don’t have an accord it really didn’t have an obligation by any means to serve any role. But the UN has determined to serve in that function. I think that is very positive. The FARC has indicated its commitment the maintaining the ceasefire. The government has as well; until December 31. And former President Uribe and the “no” campaign have also expressed their support and desire for the ceasefire to continue.

Q: On the question of timing, President Santos is confident that a new peace deal will happen soon. Why is it important for Colombia to get this peace agreement wrapped up quickly?

Whitaker: One of the factors is the one I just mentioned about the condition of FARC fighters. Another one is that these negotiations, including the public and private phases, have been going on for six years. There is a real desire to come to a conclusion on this. In Colombia, like anywhere else, there are political cycles here. There is a national election in March of 2018 where all senators, representatives, and the president of the republic will be elected. To me it makes good sense to take in both of those factors to move as rapidly as possible to have the best possible accord on alterations that would make this a more broadly accepted accord.

Q: How can Colombia start talking about growth, investment, infrastructure in ways that aren’t viewed through the peace prism? And how can the United States help Colombia in areas such as infrastructure without talking about peace?

Whitaker: Peace will bring enormous advantages, including with respect to the issues that you mentioned. There is no question about that. In fact, up to October 2 I was regularly getting inquiries from US companies. It is intriguing and interesting that a country of this size and wealth and with the natural resources it has might come on the map in a much more significant way because of peace.

Having said that, Colombia is a country which has attracted substantial FDI (foreign direct investment) over the course of the last eight years, one of the best records in South America. It has the best growth rate in South America. This year they will probably be south of three percent, next year they will probably be a little bit less than that. Two and a half percent is a pretty good result in this climate. They have an FTA (free trade agreement) with us, with the Europeans, with South Korea, with Japan. So they are clearly looking toward penetrating the global economic environment. They are doing it already now and in that way seeking a better life for the greatest number of Colombian people.

Obviously it is better if peace is achieved, but this dynamic, this momentum, this trajectory of Colombia toward greater economic engagement and competing successfully on the world stage has already been established.

Q: Is Peace Colombia funding contingent on a peace deal being implemented?

Whitaker: The executive requested this funding in the anticipation that there would be an accord and then a post-accord period. My hope and even my expectation is that an accord will be achieved. Knowing the timelines that our government works on, from my perspective as ambassador to Colombia I think it is important that we press on on that.

Our colleagues in Congress can ask very legitimate questions about how do we see that and given the current situation and what happened on October 2 where do we find ourselves now. Those questions deserve answers.

Ashish Kumar Sen is deputy director of communications at the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @AshishSen.

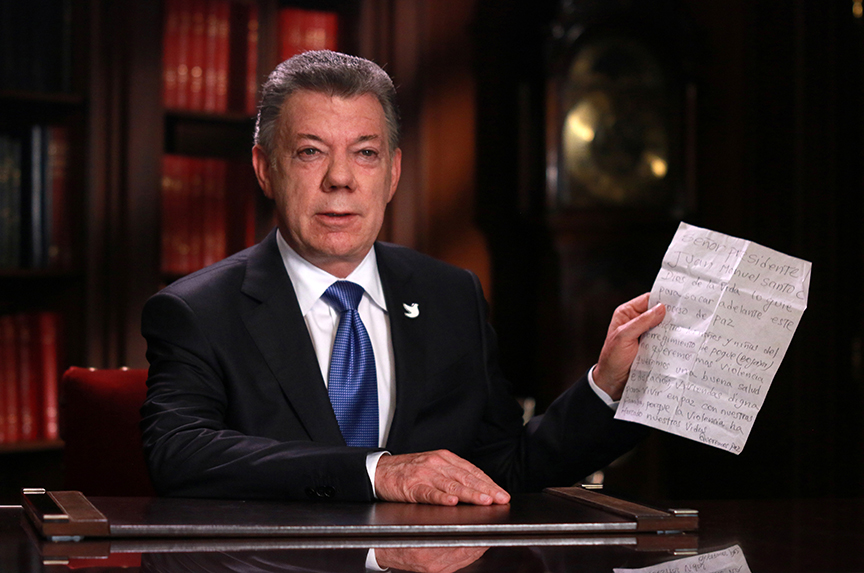

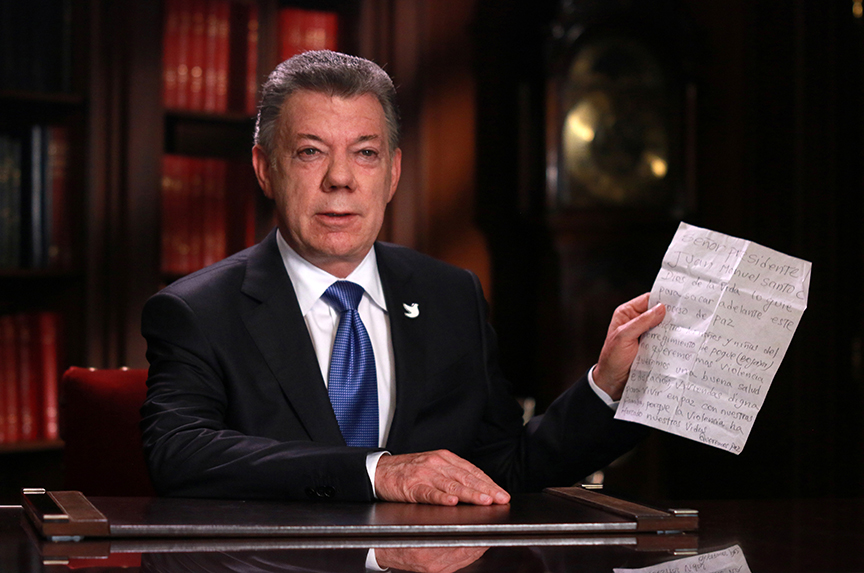

Image: Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos delivered a presidential address in Bogotá, Colombia, on October 10. (Colombian Presidency/Handout via Reuters)